COVID-19 vaccinations highlight divisions in an otherwise connected society

During the pandemic Aimee has been working as a vaccination project manager supporting in-school vaccination programmes. In her essay she highlights the disparities in uptake she encountered and how they tried to overcome them.

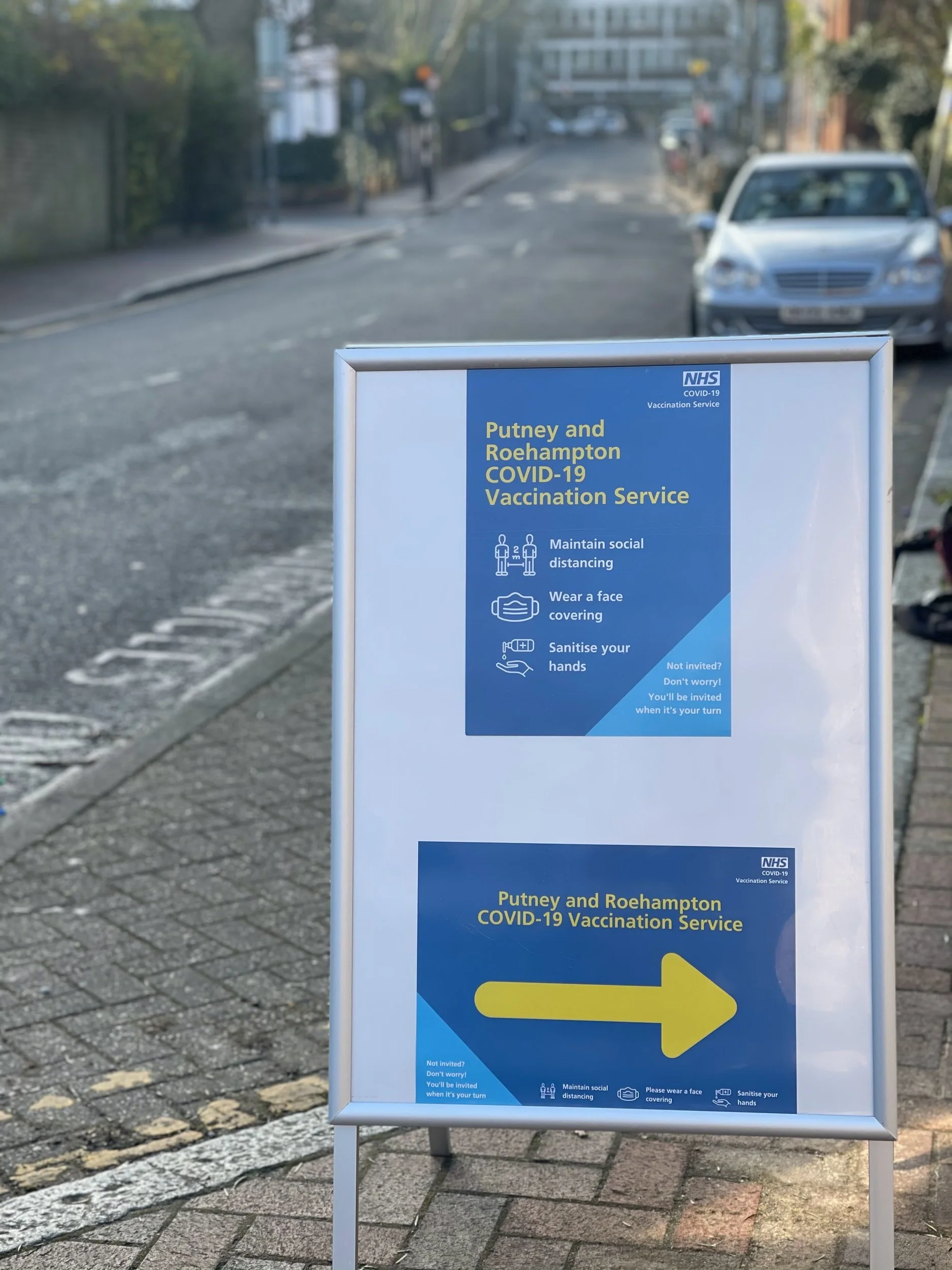

The pandemic has challenged us to consider others and band together in a joint effort toward one common goal. One of the most successful aspects of the COVID-19 response in the United Kingdom (UK) has been the National Health Service (NHS) vaccination effort—to date over 90% of individuals aged 12 and over have received their first dose and over 86% have received their second. This impressive uptake of vaccination achieved at a national level has unfortunately masked huge demographic, geographic, and socioeconomic inequities in uptake.

Specifically, across south east London, it quickly became obvious early in the vaccination campaign that significant disparities in uptake existed. For example, when considering our in-school offer for pupils aged 12–17 years, the lowest uptake and greatest challenges presented themselves in one borough*, including barriers we had not anticipated nor experienced across the other regions of south east London.

“We are continually evolving this process in an effort to ensure no one is disadvantaged or denied a vaccine they seek.”

The most surprising barriers occurred with our vaccination team’s electronic consent form—a national requirement prior to vaccinating a child younger than 16 years old who is unaccompanied by a parent during the school day.

Image courtesy of Unsplash

Firstly, there was a technology limitation in accessing the form. We had wrongly assumed, especially after the pandemic caused mass migration of in-person service to online services, that everyone would have a computer or smartphone with internet browsing capabilities. Unfortunately, this was not reality—mobile phone data plans and home Wi-Fi connectivity are not universal, and parents faced issues accessing our forms. There were numerous discussions surrounding a bespoke offer with paper-based consent forms, but the operational challenges that would come with this could not be overlooked. Historically, there have been significant delays in returning paper consent forms in a timely manner, whereas the electronic consent form offers real-time data capture for our team. This allows us to make informed decisions when ordering vaccine stock and staffing our clinical team for the day, thereby reducing waste and considering economic costs.

Secondly, literacy limitation was a barrier to understanding the form. There is a high proportion of non-English speakers in this borough, and for those, the average reading comprehension age is low. Thus, the wording in our consent form was unintentionally too complex.

In response to these concerns, we trialled an interim solution whereby we circulated a simplified consent form with only one question: “Do you wish to have your child vaccinated at the upcoming school visit?” We then followed-up with a phone call to all interested parents so that we could capture the required clinical information that had been removed from the original form. This solution has shown some promise in reaching this community, although we are still relying on technology for the initial statement of interest and language barriers persist. Moving forward, we need additional translation assistance and more tailored solutions to the technology limitations observed. We are continually evolving this process in an effort to ensure no one is disadvantaged or denied a vaccine they seek.

“Although these viruses do not recognise race, ethnicity, language, or wealth, socioeconomic status undoubtedly gives some individuals an advantage over others”

Feedback from parents who work long hours and are unable to arrange alternative appointments for their children is overwhelmingly in favour of the in-school vaccination offer, making the low uptake observed all the more disappointing. The COVID-19 vaccine is only one of numerous childhood vaccines that are offered in school settings, including HPV, influenza, and MenACWY for example. Although these viruses do not recognise race, ethnicity, language, or wealth, socioeconomic status undoubtedly gives some individuals an advantage over others. Certain communities are better equipped to access publicly-available resources and have more tools to maintain protection against viruses.

Despite public opinion and relaxed governmental regulations in the UK, the COVID-19 pandemic is not over. The virus is still circulating across the globe, maintaining an invisible link between us all. I suspect that COVID-19 will continue to circulate indefinitely, mutating each year and continuing to impact our health and wellbeing. There will also be knock-on social effects as unvaccinated individuals are unable to partake in activities and travel where proof of vaccination is required. Additionally, other vaccine-preventable viruses whose profiles have been lowered over the last two years remain a threat. Thus, devising creative solutions to increase access among vulnerable communities who seek vaccinations must remain a priority even beyond this pandemic.

*Due to NHS privacy policies, identifiable information of specific individuals and/or communities is not disclosed. The above essay is a personal reflection on the COVID-19 vaccination campaign across south east London. It is based on professional experiences from within the NHS and is not intended to be taken as absolute fact.