Metamorphosis

This poem is about the poet’s grappling with their gender presentation as a non-binary transgender person, particularly their decision to go through hormone replacement therapy or not. While large biological changes can be intimidating and frightening, they’re equally natural, beautiful, and transformative.

This poem is about the poet’s grappling with their gender presentation as a non-binary transgender person, particularly their decision to go through hormone replacement therapy or not. While large biological changes can be intimidating and frightening, they’re equally natural, beautiful, and transformative.

Image credit: Unsplash

All my friends got top surgery this year, and I think I understand

The need to find a permanent kind of remaking: to stretch the clay,

Wield shape in the intention of hands building. I am afraid to be my

Own Creator, let the masculinity drip off me like water, let my hair sprout

Beyond its harvest. Maybe the collapse comes before the expanse,

Maybe home is only made known through its absence. What I do know is

Something is eating me alive from the very guts of my frame and I am

Still here. I am trying not to build a gender out of mirrors, or belonging

Out of needles, know the seed needs to crack before the bloom. Bursting

Into becoming is indulgently natural, peacock feathers splayed, lion's

Mane kind of extravagant. For now, I stare at a magnified reflection,

Tweezers in hand. Shaky fingers pluck at the black roots, exhaling cobwebs

Out of my ribcage. I do not think belonging is a place, but it took a crash to

Make a universe, home exploding into being where there was once only void.

I am still reaching in dark, waiting to sink my teeth into the someone I could

Become. I think conservation only dreamed in white imaginations, the rest

Of us know the warmth of entropy, of always being undone, the light of tidal

Shifting, crystal refractions of all the colors we have yet to dream. I am

Threadbare and breaking, cutting loose all that makes me smaller.

I have been small for long enough.

The heroes we are not

Oluwaseun uses poetry to describe the frustrations and exhaustion that comes with being a frontline healthcare worker despite their bravery and commitment being celebrated by others.

Oluwaseun was inspired to write this piece after experiencing what it was like to work on the frontline with a tired team. She explores how when her colleagues and herself want to discuss issues that they face us as a staff group, people often make remarks that denies them a place to express their feelings in a safe space. This poem explores that frustration and the toll that it can take on already tired healthcare professionals, who really love what they do, but still want to be seen as people.

Image credit: Unsplash

Today, like any other day, I put my uniform on and wear the badge of hero, national treasure

The burden, the burden.

Has anyone stopped to look at the woman who wears the badge?

“I can’t be the only one”

I know I am not.

This hero, as human as she is, as every one of us is, chose to rise today

She chose to rise, work, and give.

I’m a little tired, but so is the woman who has been here for 8 hours with no answers in a room full of people she doesn’t know

“Am I carrying too much? Can I do more?

I wish I could I wish we could.”

We are all in this together; the comradery is incredible

I still smile and get excited at the thought of another day growing and serving

I still think it is a privilege

But my reserves are hollow barrels now

“We are very busy at the moment. I’m sorry it has taken so long for us to get to you”

I’ve said that too many times.

The woman, the man, the child, the being

They bring their fears here

Asking us to hold onto them with dignity and honour

I see them and carry them

But the problem is

I am human too

We all are

“We need to get this right and do better, we can’t have this for the patients”

That’s true,

You’re right but has anyone stopped to look at me? At all of us?

The people in the uniforms

We come with our perfectly flawed conceptions, personality traits, and tendencies

We come with our problems, our ideas, our brilliance

Our conflicts

We come with the wholeness of who we are

These things are what we serve with

Does anyone see that?

Image credit: Unsplash

We come with mistakes and through our reflections we rise up from them together

Is there any grace for that?

Is there any grace for the people who, with courage and limited resources, give?

Is this house still holding us?

When we pour out the maps of our minds and the burdens of our hearts will you still call us heroes?

Is there space for a garden to bloom?

I am like any other woman who chooses to rise and stand

Whether she is in a classroom, a home, an office or a business

I am not a hero; I don’t think I ever will be

If heroes are silenced when they protest and speak then I never hope to be that.

What I am is human

And, I will be that till the day I die.

And, what I put on is courage

I have seen the depths of what it means to be human in my uniform

In anger, in confusion, in sadness, in trauma

I have seen the rawness of it, its poignance

For that I will not be a hero

I will be a human, learning day by day, as I choose to wear my uniform.

Artist spotlight: Becki

Po Ruby speaks to Becki, a multimedia artist who uses creativity as a way to channel difficult thoughts and emotions into something positive.

Content warning: This article contains discussions of self-harm.

Becki is a multimedia artist and writer from Cardiff, Wales. Her work is influenced by her interests in philosophy, psychology, and esoterica. We connected to talk about art as a coping mechanism, transformative materials, and the power of colour.

Po: Where are you from and where did you grow up?

Becki: I’m from Cardiff, and I’ve lived in South Wales my whole life. My Welsh identity is really important to me. Although none of the adults who raised me speak any Welsh, I’m raising my own son to be bilingual. Culturally, a lot of my family comes from an Irish Catholic background, so I feel deeply Celtic and not at all British.

Everything is going to be alright

Image credit: Becki

What place did creativity have in your life when you were growing up?

Creativity was always an escape for me. From a very young age I was a voracious reader, and I used my vivid imagination to create fantasy worlds to play in. But coming from a low-income working-class home, most of the life advice I was given was to study something academic that would lead to a well-paid career and financial security. So, I pursued academic subjects that allowed me to at least think creatively, and gained my degree in Politics and Philosophy from Cardiff University.

When did you start making art on a more regular basis, and what spurred you to do so?

During my degree, art came crashing back into my life after a series of realisations about my health and the support I received as a result. Living independently for the first time was a real struggle for me—I had trouble managing my time, juggling work, studying, and keeping track of all the things I was supposed to do. Eventually I missed an exam because I genuinely just got the time wrong, and I was diagnosed with dyspraxia through the student support service.

I was also very depressed and anxious at university. I self-harmed regularly from the age of 14, but during my first year at university it became a nearly daily habit, and I was drinking huge amounts of alcohol and smoking cigarettes to self-medicate. People who knew me at that time have since told me, “I honestly thought you were going to end up dead.”

Stay here

Image credit: Becki

It was during this destructive cycle that I met Hannah Morgan, and it was literally life changing. Hannah was the first person I’d ever met who had been in a similar position to myself and had come out the other side. She was in the process of setting up Heads Above The Waves, a non-profit supporting young people with mental health problems. Along with her co-founder, Si, Hannah helped me to realise that I had the power to stop hurting myself and to channel that emotional energy in other ways.

As a result of her advice and support, I returned to creativity. At first my creations were very dark—literally and emotionally—as I processed difficult experiences. I didn’t have much money, so I worked a lot with found and recycled materials: collaging with cut up cereal boxes, sweet wrappers, and junk mail. These creations shifted my perspective, and I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis. I haven’t stopped creating since then.

You are who you have always been

Image credit: Becki

“I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis.”

You experiment with mixed mediums in your artwork. What do these materials mean to you?

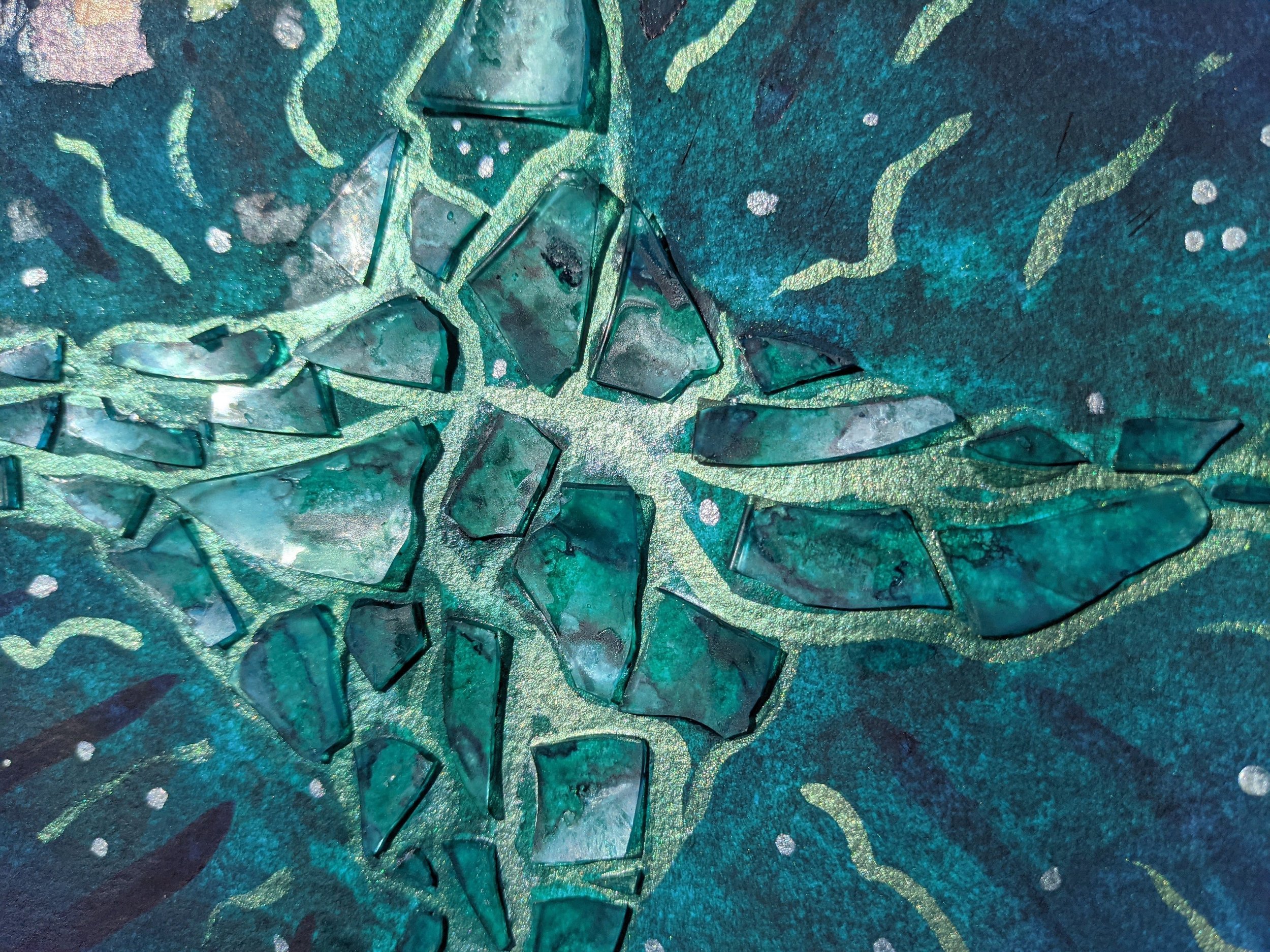

Broken glass, in particular, holds a lot of emotional significance for me. I frequently have accidents and break things, which I now know is due to dyspraxia. But before I was diagnosed, I got into trouble a lot for being “careless”, “thoughtless”, and “ungrateful”. I internalised these criticisms and saw every broken cup as evidence of how deeply terrible I was. It was because of these feelings that I first picked up a shard of a glass I’d just dropped and used it to cut myself.

Glass was my tool of choice for self-harm, and I was never short of it, so using it in my artwork feels transformational, alchemical; I’m taking something with intense negative associations and making it neutral. In my latest collection, I feel like the watercolours represent the soul, or personality, and the glass is trauma. Trauma happens to all of us: it’s undeniable and it shapes the way we develop. But our soul and personality hold the potential of absorbing and growing around these painful experiences to become a more complex and beautiful version of who we already were. I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them. But I do think it’s valuable and an important part of the healing process to look directly at the trauma and acknowledge the tangible ways it has affected you.

“I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them.”

The cracks are how the light gets in

Image credit: Becki

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic process: is creativity spontaneous for you, or do you choose a time and place to work on an art piece?

Both! I’ve worked hard to learn to use art as a replacement for self-destructive behaviours or as a reaction to overwhelming experiences. I have stashed notebooks and scrapbooks in every room of the house, and whenever I feel the need, I grab one and doodle or write whatever it is that I need to get out of my head. Sometimes I just grab a stack of magazines and start flicking through and ripping things out with no plan in mind, just to occupy my hands while my mind-body relaxes.

I also plan pieces that I want to make, sketch them in a scrapbook, and then create them carefully over the course of several days. I find that having regular practice gives me the space to keep my mind calm day-to-day. Painting, collaging, building glass mosaics with tweezers: these are my versions of meditation. I can’t sit still and think of nothing, that’s impossibly uncomfortable for me, but I can be present with myself on the page.

Do you create art primarily for yourself?

At first it was mostly for myself, but since I started working with Heads Above The Waves, I began to focus more on the positive side. I didn’t want my art to be a rumination on all the depths of my lowest moments; I want it to be a little beacon of hope and for people to see it and feel that they’re not alone.

On your Instagram page your bio reads “turning wounds into wisdom”. What does this mean with regard to your art?

Still expanding

Image credit: Becki

I actually have a tattoo that reads “turn your wounds into wisdom”. I’ve held onto this idea for a long time: I’m not broken, or damaged—I’m learning. This is the value I can bring to my community: my experience, my healing, the lessons I’ve learned. I want to help people find the path out of their pain.

Unlike a lot of art that centres around themes of pain, madness, and politics, your work is comparatively very pretty and colourful. Is this a conscious choice?

Absolutely. I feel like colour has so much power, and I think there’s already more than enough art that dwells on the darker side of things. For me, I find comfort in numinous colour, and in remembering the scope and depth of beauty that exists. In an ideal world, looking at my art would remind others of this scope and beauty, too.

You identify yourself as Welsh, neurodivergent, chronically ill, and queer. How do these identities overlap and impact your creative process?

These labels are important to me because they are the communities that have welcomed me, held me, and allowed me to discover myself. Along with my diagnosis of dyspraxia, I have Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), and developed fibromyalgia following a pulmonary embolism in 2016. I think there’s a common feeling of relief among many neurodivergent and chronically ill people in finding online communities and suddenly connecting with other people living a similar experience as you. Finding these communities has made my life bearable in ways that I can’t completely articulate, but my creativity is often a reflection of these identities and processes.

You deserve good love

Image credit: Becki

We spoke about the potential of you doing an exhibition with Heads Above the Waves in the future. What draws you to this possibility?

Without Heads Above The Waves, I don’t think I would be an artist today. I might not even be alive. Putting work out into the world where it can reach people could make a tangible change for somebody who needs one. It feels valuable to be both carving this path for myself, and sharing as I go for the benefit of others coming after. I want to prove (to myself as much as anyone else) that it’s possible to live a balanced, fulfilling life as a disabled, chronically ill person.

Heads Above The Waves is a non-for-profit organisation that raises awareness of depression and self-harm in young people. They promote positive and creative ways of dealing with bad days. Advice, positive coping techniques, and other people’s experiences can be found on their website.

For urgent support in the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or you can email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org

Tiles

Emily reflects on the experience of working as a healthcare professional serving rural communities. This poem draws on the inspiration from colour and its contrast to the surrounding setting.

During my undergraduate degree, I completed a semester abroad in South India, where I took Public Health courses through a local university. As part of the programme we went to field visits once a week in the local community. This poem is about one of our visits to a tile factory. I was struck by the state of the factory: a dilapidated building strewn about with broken tiles, bricks, and the like. Dimly lit and dusty, the air was loud with the cranking of machines and the slapping of clay against oiled metal. In the midst of this relative chaos, women decorated by brightly coloured kurtas were working to make bricks on the lower level of the building. I was struck immediately by the contrast between the bright fabric of their clothes, and the dust and dinge that whirled around them. The image of these women, appearing in such stark contrast to their surroundings has stayed with me and from it this poem materialised.

Image credit: Unsplash

A girl walks the line,

Skirt drawn

Hands caked with clay

A grey streak marks her a laborer.

Sweat glistens in the sunlight that has snuck through the thick air

Her arms carry what will one day be a home

While her body,

covered by the dust of another man's future,

Is already home to her own.

Artist spotlight: David

Gwen features the works and journey of artist, photographer, and entrepreneur, David. David advocates for physical and mental wellbeing to support the health of communities.

Content warning: this article contains mentions of racism and mental illness.

Back in 2019, David Lee turned his camera towards me. I felt self-conscious and suddenly didn’t know how to be natural in my own skin. But his approach to photography centred on connection and introspection, which made the experience more like a cathartic release than a purely aesthetic pursuit. He gave me the opportunity to talk about the things that were on my mind and reminded me how to be myself again. David and I met as community advocates who were still exploring the ways that we fit into supporting the social, environmental, economic, and health needs of our microcosm of community. Most of our conversations were about how we work in relationship to the community and how we take care of ourselves. That night in my flat we had the same conversation but somehow it felt more vulnerable to have a camera there and to have it be documented: at the same time, it was therapeutic to have those moments preserved. David has taken that intimacy of documentation and turned it into his full-time pursuit as a photographer and artist.

Photography by David Lee

Creativity has always had a place in David’s life, but his emergence as a creative was tangled with his identity and wrangling with others’ perceptions of him. He recalls that different learning environments impacted the reception of his art by his teachers. Early on he was not encouraged to pursue art, which raised larger questions on how stereotyped identities, specifically expectations of black people, can hinder and limit growth. “I think sometimes black people are expected to perform in certain ways … looking back I didn’t get the encouragement like my peers did, and I won’t say why, but I noticed that, and it got to me.”

Photography by David Lee

Initially, this kept David from identifying as a creative. It wasn’t until middle school that his poetry was recognised and won a competition. “I remember winning that and the first time feeling like I was a creative. Like my school actually did think it was a big deal. The school was majority black and that was the first time I went to a predominantly black school.” This recognition and ability to self-identify as someone who is creative gave David license to continue exploring his art, which soon led him to photography.

His exploration of photography began as an ode to memories and an outlet for his own depression. Looking through old family photos in what his family called their “library”, David became interested in photos and memory. “These memories are important. I realised how important they were to me. So, I went and bought a bunch of disposable cameras and went around taking pictures of middle school.” Reflecting back on this period of time, David recounts some of his own struggles with depression and finding photography and poetry as a means of dealing with his own internal world.

“I can see that’s when my childhood depression started to manifest the most and so I needed these outlets. Friendships were starting to look weird … my art usually centres around mental health and trying to create these outlets of expression so people can process and see themselves reflected back. I think that’s when it started for me.”

Photography by David Lee

Memories of middle school years are ones he has shared with me a couple times, and it brings together so many aspects of David that I’ve come to know. He has an incredible ability to capture vulnerable, authentic moments. Part of his art is tapping into the undercurrent of a moment and pulling out the right words and images that describe some of those unspoken emotions. Photography is his way of slowing things down in an age of hyper-stimulation. “It’s a chance to press pause and allow people to go back to that moment and think about what they were feeling and see the subtleties of who they are”. Oftentimes, David shares his photos with poems and prose about that moment, the interaction, or what the experience brought him. Whenever I see David’s work, photography and poetry paired together, there is no doubt it’s his voice and vision that come through.

Photography by David Lee

“Photography is his way of slowing things down in an age of hyper-stimulation. “It’s a chance to press pause and allow people to go back to that moment and think about what they were feeling and see the subtleties of who they are.””

During the summer of 2020, George Floyd was murdered. Black Lives Matter protests spread across the United States and around the world. David was there—documenting through his lens the rawness of the people, the protests, the events, and the emotions.

The pandemic was ongoing in the backdrop, which brought into sharp focus health inequities, particularly in black communities. The broader social conversation around racism, critiques of the carceral system, and health inequities shifted—it was suddenly more critical, urgent, and mainstream. “During those protests I realised this wasn’t my space anymore. I started to see allies showing up and screaming at the top of their lungs, with signs and linking arms on the frontlines. Like ‘Huh, cool it’s been done’ and it felt like the energy shifted. So where do I need to go if this isn’t the space, because the work needs to continue. I chose physical health, community, and mental health. Getting outdoors was the way to do it.” The protests in 2020 felt different to him and having allies show up in those spaces offered David the flexibility to do the work he really wanted to do. This was when he transitioned to being a full-time co-founder and photographer.

Photography by David Lee

Choosing the name of his organisation was an act of radical self-naming and claiming an identity. David reflects: “How is that going to come off to people, is that marketable? But in my community it’s important to say this is who we are and not allow other people to dictate what our expression should be. … So, I started the organisation Negus in Nature (NIN) with my business partner Langston”.

Within NIN, David is in his element—sharing the joys of the back country while documenting a community becoming connected with their mental and physical wellbeing outdoors. He’ll be starting his artist residency at the Kala Institute, which will give him access to an array of mixed media materials. He’s really excited to be sharing some of his new works coming up as he says, “A lot of the protest photos I have not shared yet because it’s like ‘aight this is raw and I don’t know what this is for just yet … and so now everything is coming together and it’s this collective idea of ‘this is where I was in the pandemic and this is where I was before and this is the processing.’” He wouldn’t share much more about his upcoming project, but he’s dreaming up something with paper mâché, dabbling into the world of mixed media.

Stay up to date with David’s projects on Instagram: @d.xoti

You can follow NIN’s adventures on Instagram: @negusinnature

If you want to sign up for an excursion you can visit NIN’s website

Photography feature: glimpses of the Gambia

Through photographs Franca shares her own day-to-day experiences working as a non-local Research Assistant in The Gambia.

For the last two months I was volunteering at The Gambia Medical Research Council (MRC) as a research physician. During this time, I gained some insights into the communities and the ways of living and learnt a little bit more about the health seeking behaviours.

These photos reflect scenes I encountered in the ordinary course of my day working as a non-local medical professional. This experience provided me with a perspective that is not all encompassing of life in The Gambia, but rather a glimpse into my own perceptions.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

9.00am: Every day before work, my colleagues would stop for a sandwich with onions fried in palm oil and bean fritters, which costs about 15 Dalasi (roughly 20 pence). A piece of fruit is often more expensive. An apple, which can be found in every fruit stand, costs twice as much as they are imported—like much of the food consumed in The Gambia. My colleagues told me that many Gambians’ diet is low in fresh fruits and vegetables, not only due to lifestyle habits, but also because of costs. One survey showed that only 22% of the Gambian population eat 5 portions of fruit and vegetables daily.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

10.00am: We bounce up and down in the car as we drive along the bumpy roads of a peri-urban zone. Most of the roads and properties are unpaved. During the rainy season, the unpaved roads become waterlogged. Goats, donkeys, and dogs romp around, and children play in the puddles.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

11.00am: As part of my duties as a research physician on an observational trial, I visited households in urban and rural areas. I saw a high prevalence of skin diseases—particularly in children—including bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections. Affected individuals or their parents had often not sought or found adequate medical attention yet, in some cases for long-lasting manifestations or deep abscesses. The prevalence of children in this area with skin infections after the rainy season can increase to 16%, and those with pyoderma to 23%.

12.00pm: We would often smell and see smoke in the courtyards we visited, as lunch was prepared. Commonly, tea or food is cooked on smoking coals in the courtyard or in a hut of the compound. According to the latest Demographic and Health Survey, 80% of households in The Gambia use charcoal or wood for cooking.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

5.00pm: In the evenings, I would sometimes go for a stroll in the market. On one occasion, I met a shopkeeper who told me that he considers the health system in the urban areas to work well, and only a small flat fee is charged for visiting health centres and hospitals. However, the field team I worked with said that there is varying quality in healthcare services and often shortages in medicines. In many cases, people have to pay for medicines out of their own pockets in pharmacies, which can be a relatively big expenditure, especially when it comes to chronic diseases. It is estimated that 20% of people spend more than 10% of their household consumption or income on out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

6.00pm: On the beach front, many women sold fruit at stalls like these. Two years ago, these would have been bustling during the high tourist season, but COVID-19 has halted tourism in the country. The tourism industry is a major contributor to Gross Domestic Product in The Gambia and many are reliant on its revenue for their livelihoods. I spoke to a 20-year-old fruit seller who told me that her income from these stands assisted with her family’s expenses.

Photography by Franca Conradis-Jansen

7.00pm: In the evenings and on Sundays, the beach becomes a hub for exercise, including football, rugby, jogging, or gymnastics. The beaches are open to all social groups, but I observed very few women exercising. Lack of physical activity may be one of the factors contributing to the fact that women are twice as likely as men to be affected by obesity in The Gambia.