Cancer survival: due to patient or healthcare system characteristics?

Matthew argues that rapid cancer diagnostic pathways must be equally and proportionally accessible to all patients in order to close the deprivation gap in cancer survival rates.

Cancer survival is improving and has doubled in the last 40 years in the United Kingdom. However, the increase in survival has not been the same for everyone: it is leaving behind those who are more deprived.

Figure 1: Five-year relative survival (%) by deprivation category (detailed later) and calendar period of diagnosis in England and Wales. Relative survival, or net survival, is the survival probability derived solely from the cancer-specific hazard (risk) of dying and is independent of the general population mortality, i.e., competing risks of death.

Figure courtesy of Bernard Rachet, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

Until the early 2000s, less than half of people diagnosed with cancer were expected to live for five years. Since the introduction of the National Health Service’s (NHS) Cancer Plan in 2000, cancer survival has rapidly increased. The NHS Cancer Plan, and successive cancer policies, recognised the importance of an earlier diagnosis on the chances of a good prognosis. Thus, there was a greater drive to increase the proportion of patients diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Over the past two decades, the proportion of patients having their cancer detected earlier has dramatically increased, contributing to the rise in cancer survival. This trend is in large part due to factors such as awareness campaigns (e.g., association of smoking and risk of lung cancer), cancer screening initiatives (e.g., checking for lumps in breast cancers), and advancements in treatments and technology (e.g., positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans).

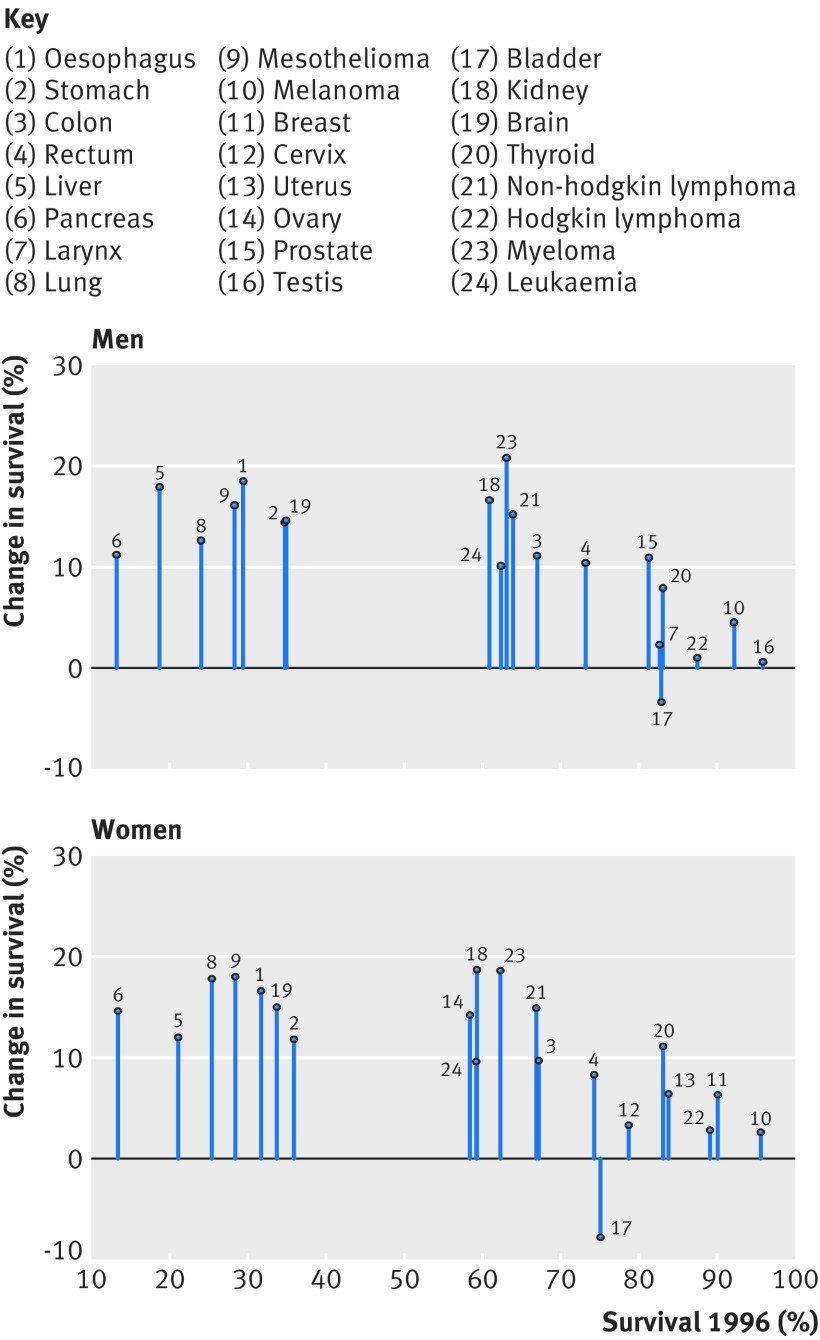

Figure 2: Change in one-year net survival between 1996 and 2013 for 20 cancers in men and 21 cancers in women. For example, amongst women, patients with pancreatic cancer had the lowest survival in 1996 but survival increased by approximately 15% by 2013.

Figure courtesy of Aimilia Exarchakou, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

In population-based cancer survival research, the measure of deprivation has evolved from a composition of Karl Marx’s structural and Max Weber’s societal perspectives. It is defined as the socially derived economic factors that influence what positions individuals or groups hold within the multi-faceted structure of society. Deprivation is a contextual measure of not only income but of one’s opportunities within their immediate area that are identified by several domains (employment, education, etc.). An individual’s assigned deprivation level is determined by the rank of their area relative to other areas in terms of a weighted combination of the domains. Thus, an individual’s level of deprivation is (i) an ecological measure and (ii) relative to other individuals. The latter is an important characteristic to consider since the areas with lower ranks are interpreted as more deprived areas compared to areas with higher ranks: they are not necessarily all deprived areas.

However, for some cancers, survival amongst those living in least deprived areas has improved faster than in more deprived areas. In other words, an unexpected but obvious phenomenon has occurred: there has been a marginal increase in survival, but the difference between deprivation groups has grown wider. Amongst males, the greatest widening was observed for melanoma, prostate, colorectal, and haematological malignancies; amongst females, it was gynecologic cancers. What is less obvious but no less important is that, apart from lung and brain cancers, the deprivation gap for any cancer has not narrowed. The bottom line is that these cancer plans have not targeted all patients equitably; they have missed patients who are living in more deprived areas.

Reasons for persistent inequalities

Unless the deprivation gap in survival is addressed, these inequalities are expected to persist or even widen in some cases. Cancer survival is often described by patient characteristics, such as sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic level. This has contributed to a common public misconception that patients with certain characteristics are predetermined to have lower chances of survival; however, patient characteristics account for approximately only a third of the socioeconomic inequalities. In fact, most of the socioeconomic inequalities in survival are due to unknown factors (other than patient characteristics). Optimal interactions between the patient and the healthcare system around the time of cancer diagnosis can drastically increase a patient’s chances of a better prognosis. Such optimal interactions include: effective communication during a general practitioner (GP) appointment, distinguishing between comorbid and cancer-related symptoms, being referred from a GP to a consultant within two weeks, and promptly receiving the diagnostic test and results. The problem is that these optimal interactions are less likely to be experienced by those in more deprived areas.

The current framework for cancer diagnoses is the rapid diagnostic and assessment pathway, such as the colorectal cancer diagnostic pathway (Figure 3). The aim of the diagnostic pathway is to ensure patients receive the outcome of diagnostic tests within 28 days of referral. Indeed, reducing the time that a patient is on the diagnostic pathway will contribute to an earlier diagnosis. However, to be fully effective it is crucial that the diagnostic pathway starts when the cancer is in its early stages—in reality, patients may have cancer months before they have the consultation with a GP that initiates the pathway. The diagnostic pathway could be thought of as a product of a company that is accessible to those who can “afford” it in a society where the currency is “privilege of accessible healthcare services”. It is not the function of the diagnostic pathway that is systematically biased, it is inaccessibility that induces bias.

The diagnostic pathway is susceptible to two major flaws resulting from access: GP availability and testing capacity. Firstly, the number of GPs within any area must be proportional to the size and healthcare requirements of the population they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with less GPs may have a reduced chance of accessing the diagnostic pathway. Secondly, the number of specialists and the capacity of diagnostic facilities that feature along the pathway must be proportional to the demand of any area they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with unavailable diagnostic specialists or facilities will have a reduced chance of receiving a definitive diagnostic result (including earlier diagnosis) within 28 days of a GP referral.

Figure 3: Colorectal cancer rapid diagnostic pathway. (MDT: multidisciplinary team, GP: general practitioner, CT: computed tomography, OGD: gastroscopy, CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen test, CNS: clinical nurse specialist, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, TRUS: transrectal ultrasound.)

Figure courtesy of NHS Cancer Programme (NHS England)

To elaborate on the first flaw (GP availability), the number of GPs is not only lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, but there is an exodus of GPs across England, leading to a comparatively higher workload for GPs who do work in these areas. Moreover, GP time for each patient is, on average, lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, even for patients with comorbidities. This is an example of the inverse care law: those who most need care are the least likely to receive it. Higher workload for GPs, in combination with reduced GP time, increases the chances of missing ‘red flags’ of cancer symptoms. Furthermore, more deprived areas tend to be more densely populated and have a higher prevalence of patients with comorbidities. More densely populated areas are likely to have a healthcare service with a higher demand, leading to an increased chance of patients being diagnosed through emergency route, which is closely correlated to a later cancer stage at diagnosis. A natural, and foreseeable, consequence is a future with a reduced number of cancer patients from deprived areas on the diagnostic pathway, ultimately leading to the sustained deprivation gap in cancer survival.

Figure 4: Number of registered patients per GP by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in order of deprivation level.

Figure courtesy of The Health Foundation

To elaborate on the second major flaw (testing capacity), a key phase of the cancer diagnostic pathway is during Days 3 and 14 (the Straight to Test [STT] phase), when the cancer-specific test is expected to occur. One commonly required procedure is a computed tomography (CT) scan, which is carried out by a radiologist. The same issues around accessibility materialise again: not only is there a radiologist shortfall, but millions are spent on scan outsourcing. Some of the key findings of the Royal College of Radiologists’ (RCR) annual census (2020) were that the UK radiologist workforce is now 33% short-staffed, with a projected rise to 44% by 2025. Additionally, consultant attrition remained at an average of 4% within the UK. Previous data from the RCR highlighted that scan outsourcing in 2017 rose by 32% since 2016. The cost of scan outsourcing (paying private companies to help with the workload) was estimated to be £116m in 2017 (enough to pay 1,300 full-time radiologists). With no clear influx of radiologists, and an increasing demand for CT scan usage over the next few years, the deprivation gap in cancer survival is unlikely to narrow.

Reducing inequalities

There are multiple factors contributing to socioeconomic inequalities. However, increasing the NHS budget to improve the ratio of patients to GPs and radiologists would drastically reduce the deprivation gap in cancer survival. The healthcare system can only go so far as to be more efficient with the same budget; each year, there is a higher demand for additional services that heavily outweighs the annual increase of the NHS budget. Even advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis, comes with its own inherent inductive bias that may itself contribute to the deprivation gap in survival. Without the appropriate capacity for demand in the areas where care is most needed, it is unlikely that we will see a reduction of the socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival and the true potential of faster cancer diagnostic pathways.

Operation waitlist: barriers to life-saving surgeries

Rishabh breaks down the different barriers to care and explains how surrounding resources can influence surgical outcomes.

Even with the dazzling advancements in healthcare in the past 50 years, barriers to care seem to remain an unfortunate motif that stands in the way of improved collective health outcomes. Limited access to healthcare leads to suboptimal care for patients, which can carry serious consequences for some of the most acute cases—particularly those who require emergency surgical intervention. The conversation surrounding available resources and surgical outcomes is not a new one, and many of these disparities have been characterised over the years across various surgical subfields, from surgical oncology to paediatric neurosurgery. To make matters more complicated, the COVID-19 pandemic serves as an additional stressor and has compounded the strain on healthcare systems trying to meet the needs of their patient population.

Image credit: Unsplash

First, a number of pre-existing upstream elements can impede a patient’s ability to seek care. The social determinants of health are factors that include characteristics of a patient’s environment that may appear far removed from formal healthcare processes, but still significantly affect the patient’s health outcomes. For example, a patient’s limited access to nutritious food, clean water, education, and a safe living environment may predispose them to more serious conditions and complications in their surgical care than if they enjoyed unrestricted access to such resources. This too has been studied extensively, leading organisations such as the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States (US) to develop a myriad of programmes targeting the social determinants of health in underserved communities. Similarly, on the healthcare systems end, limitations in resources result in unequal outcomes. Rural and county hospitals experiencing personnel shortages, overwhelming demand for operative treatment, and limited financial assets, tend to fare worse than their counterparts in outcomes such as post-operative mortality. This is deeply concerning, given that rural and county hospitals often care for patients with more comorbidities and limited resources.

In the last year and a half, the COVID-19 pandemic has further strained an already stressed system in the US. As a result of personnel shortages, bed unavailability, and the precautionary delay of non-urgent operations, there is currently a significant backlog of desperately needed surgeries. Taken together, these factors have also led to the loss of revenue for academic and non-academic hospitals, jeopardising their ability to take care of patients in the future. Even so, the COVID-19 pandemic has not affected all hospitals equally. In the US, safety-net hospitals—which care for the uninsured and underserved—saw their profits dwindle, while their private counterparts experienced an increase in revenues. In part, this discrepancy is due to anticipatory financial planning by private hospitals, but it is also a result of the federal government’s pre-pandemic initiative to allocate relief funds to hospitals commensurate with their revenues. Additionally, because the safety-net patient population tends to be sicker, more vulnerable, and require more intensive resources, these patients have suffered disproportionately along with the very hospitals tasked with caring for them.

“Bridging the resource gap and the outcome chasm cannot be achieved in one day. Indeed, social inequities present barriers to patient care in healthcare systems around the world. ”

In response to this exacerbation of existing disparities, hospital systems around the world have taken steps to provide adequate care. After all, the consequences of complacency in the face of limited resources are dire. Backlog in the cancer referral pathway, for example, could cause a significant excess in death rates according to a study designed to measure the effects of delayed referral in the United Kingdom. To optimise resources, various techniques have been implemented to ensure surgical services can operate on as many patients as possible before their disease progresses. One such technique was deployed in a hospital in Hong Kong, which created a tiered system of cancer subtypes and assigned target completion times for the respective operations, leading to some alleviation of their waitlist burden. Furthermore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has provided guidelines for resource allocation and triaging systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. These guidelines help hospitals streamline their care so that they may treat as many surgical patients as possible given the realities of resource shortages. While endeavours such as these have eased some of the strain on healthcare institutions, systemic factors continue to unduly affect disadvantaged patients.

Bridging the resource gap and the outcome chasm cannot be achieved in one day. Indeed, social inequities present barriers to patient care in healthcare systems around the world. While steps have been taken to address these disparities, further investigation into potentially implementable solutions is more important now than ever. The goal of this pursuit is to ensure that all patients, regardless of their backgrounds or means, receive the surgical care they need.

Abortion law in context, from the perspective of a Texan

Kristen argues that a battle for political power and control lies behind the most recent abortion ban in Texas, and considers the implications of this for women and underserved populations worldwide.

Content warning: this article discusses abortion

Abortion is a touchy subject that can often elicit a broad spectrum of reactions, both from public health professionals and lay voters alike. An understood silence is even more real and raw in my home state of Texas, a place where abortion law has taken centre stage in a national debate about the role of religion in government, women’s rights, and healthcare quality. However, the pursuit of restricting women’s bodily autonomy is not so much a moral battle, as Texas legislators may like you to believe, as it is a struggle over a rapidly changing culture.

Image credit: Unsplash

When people ask, I like to describe Texas as a microcosm for all the political tension currently unfolding in the United States (US), not unlike trends in the United Kingdom (UK), France, and other countries. It’s a state that is rapidly expanding, diversifying, and simultaneously attempting to hold onto its identity. These themes appear to conflict many long-term residents, and a fierce defence of tradition, homogeneity, and intolerance has taken hold of a swath of voters. The most recent result of attempts to uphold reactionary values within the laws of the state is the Texas Heartbeat Act (Senate Bill 8), signed into law by the governor Greg Abbott on the 1 September this year, which bans abortions six weeks after conception. This bill is the most restrictive abortion law of the century, and openly defies the legal precedents set by Roe v. Wade in 1973 (a legal case in which the US Supreme Court ruled that a state law banning abortions was unconstitutional), limited though they are. Arguably, one of the most remarkable features of the legislation is that it relies on civil reporting to keep women in check, as opposed to criminal enforcement of the ruling.

Growing up as a woman in Texas has taught me many things. Chief among them is resilience, an appreciation for cultural diversity, and the belief that I can achieve anything with a hardworking spirit. However, the state’s restrictive laws placed on female freedom have defied these values, and mandated the loss of opportunity for many women, especially women of colour. Unfortunately, the novel abortion ban is one of several laws passed by the state government that reduces the freedom of its people. While the Texas legislature was drafting Senate Bill 8, it was simultaneously constructing regulations to restrict voting rights. Senate Bill 1, signed into law on 7 September, reduces the validity of mail-in voting, shutters 24/7 polling stations, and grants free movement to partisan poll watchers (volunteers who observe the election process) in voting locations. All of these restrictions target the novel initiatives developed by Harris County to facilitate voting in the 2020 presidential election. This encompassed the state’s largest and most diverse city of Houston and primarily impacted voters of colour. By passing both of these laws, Texas legislature has effectively revoked the legal rights of women of colour to receive an abortion, and to vote freely and easily.

“Texas legislature has effectively revoked the legal rights of women of colour to receive an abortion, and to vote freely and easily.”

While Republican lawmakers may refute their desire to dismantle the rights of minority groups within Texas voting pools, the restrictive abortion law currently in place is clearly not an attempt to protect unborn children. If that were the case, it would have been accompanied by sweeping child support mandates, day-care stipends, and mandatory paid parental leave. Furthermore, if the law represented the legislators’ belief that all life is sacred, they would be applying equally vigorous restrictions to gun ownership, eliminating the death penalty, and funnelling government funds towards public health measures and education. Instead, the highly religious language used to justify the ban is simply an attempt to consolidate power through the mobilisation of evangelical voters. The US prides itself on religious freedom, and reduced government involvement in matters that involve personal beliefs. However, when it comes to maintaining a significant portion of your voter base and eliminating the power of your opposition—anything is fair game.

Image credit: Unsplash

Because political complexity has created such tangible tension in Texas, it would be inaccurate to paint these events as straightforward racist acts against a large proportion of Texas residents, although their repercussions certainly have that effect. Rather, they represent the last dying breaths of a government that no longer represents the people. Texas republicans have played every move at their disposal to maintain power, including gerrymandering the most diverse portions of primarily left-leaning cities, passing the aforementioned restrictive voting laws, and mobilising evangelical values to support their claim to moral supremacy. However, Texas is changing, much like the rest of the world. The population is becoming increasingly youthful, and Texans of Hispanic heritage are set to comprise the largest demographic group in the state by 2022. These populations tend to swing left, a fact that was exemplified during the 2020 presidential election where only slightly less than half of the state voted for Joe Biden—the greatest turnout of blue votes since the state switched to red in 1980 during the election of Ronald Reagan. Reactionary representatives can see writing on the wall: it won’t be long before Texas becomes at least a toss-up state, much like Florida, where election turnover is high, and leadership is diverse.

“Restrictive abortion laws do not stand alone, and Texas’ inability to release its hold on women’s freedom is, in reality, an expression of a fear of change.”

Finally, the US Supreme Court—the highest court in the land—has done nothing to protect women and their rights against the draconian rules laid out within Senate Bill 8. Even though the court could choose to temporarily suspend the law while it considers the bill’s legality, a 5-4 decision permitted the ruling to move forward without challenge. Although it now appears the court will reconsider this position, and likely rule in favour of abortion providers, this slow action has left hundreds of women exposed to the risks of unsafe abortions and the “civil servants” hell-bent on reporting and punishing their private actions. I’m fortunate enough to now live in a country where abortions are safe and legal, but my heart breaks for other Texan women who cannot say the same, and whose government refuses to protect them. Restrictive abortion laws do not stand alone, and Texas’ inability to release its hold on women’s freedom is, in reality, an expression of a fear of change. Sadly, the reflections of a faltering democracy afflict not only Texas, or the US; Europe is well on its way to a political schism of its own. In what other ways will scapegoated women, minorities, and immigrants suffer? Illegalised abortion is simply a signpost on the road toward the erosion of human rights in the name of power.

Improving nuance in South Asian immigrant mental healthcare

Pallavi discusses the ways in which Western approaches to mental healthcare fail to recognise the nuances of immigrant communities, cultures, and conceptions of self.

If there is anything the pandemic has shown us, it is that isolation is exceptionally rattling. A June 2020 survey by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 40.19% of adults were experiencing depression, anxiety, PTSD, or substance abuse in the United States. This was three to four times higher than the rates reported just the year prior. Thus, the need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations. Yet, the diagnosis and treatments we assign to these mental health conditions often do not recognise nor appropriately address these differences. While there is some degree of universality in the human experience, there must be greater nuance and understanding in how we provide mental healthcare, especially in vulnerable and underserved populations. To illustrate this need, I will specifically be looking at how mental health is diagnosed and treated in the United States (US) and how this approach often does not work for the South Asian population here.

Image credit: Unsplash

“The need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations.”

The medical system in the US is ascribed by the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V). The DSM-V is a collaborative work created by mental health professionals to lay out guidelines for appropriately diagnosing someone with a mental health condition. Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common, annually affecting 19.1% and 10.4% of American adults respectively. For a patient suffering from anxiety, the DSM-V lays out symptoms and the level of daily impairment a patient must be experiencing to receive a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). These include the duration, breadth, and content of anxiety, as well as the presence of somatic symptoms, such as fatigue or restlessness, not explained by a different physiological cause. While the treatment varies across conditions, the overarching principle remains the same: the evidence we have supports a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. A patient diagnosed with GAD is likely to be prescribed a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) and is recommended for a therapy programme, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. Although this is considered standard treatment, the success rate of this regimen broadly varies. This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients with GAD may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways. While there are many components missing in this model, I will delve into three that I have found to be largely absent.

“This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways.”

Mental health diagnosis and treatment largely rely on using the individual as the focal point. As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold. In South Asian cultures, there is a high degree of interconnectedness between families and communities, spanning generations. Thus, the concept of ‘the individual’ is diluted. There is a protective element here; ideally, the burdens that one person may have to carry will be bolstered by a community. However, in a dysfunctional dynamic, the diminishment of the individual sphere turns into undue burdens forcibly carried by many. This ties in with the idea of intergenerational trauma. Young South Asian Americans today are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who lived to see the end of colonialism in India. Many are children of parents who immigrated to the West, facing poverty, racism, and uncertainty in a new country. These are not easy events for any generation to cope with, let alone within South Asian culture, where traumatic events are not openly spoken about. There is a profound alteration of sense of self that comes with traumatic occurrences, which can be greatly magnified when it occurs within a culture that also de-emphasises the individual. A communal notion of self can also make it difficult for a person to recognise intergenerational patterns that may be harming them. Contingently, a collectivist focus makes it difficult for many South Asians—whether they are from the era of Indian independence or they are influenced by modern-day societies—to buy into a mental healthcare system that places focus largely on the individual.

Image credit: Unsplash

“As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold.”

Language is another major barrier in providing nuanced mental healthcare. As clinicians, we use terms like “major depressive disorder” and “generalised anxiety disorder” to demystify. These labels make sense for those who work in healthcare, but what do they really mean to individuals who have never heard these terms before? What do they mean to those who do not speak English? The majority of the clinical language used to describe mental health come from a Western context and are amenable to English speakers. As seen by the portrayals in South Asian media, including cinema, a large number of South Asian languages do not use or have words that speak extensively or objectively about mental health. Thus, it becomes difficult for people to be aware of these issues, let alone act against the stigma around them, when there are barriers for communicating about them.

Finally, each community should be framed within the context of how they view the healthcare system. Like many immigrant communities, there is a degree of mistrust regarding healthcare amongst South Asians. Given the rich history of Eastern medicine within the region, there is an ongoing balance between how much trust the community will divvy up between these traditional, generational healing practices, and Western medicine. A 2016 study in BMC Endocrine Disorders looked at South Asian opinions on diabetes medicine and found a prevalent theme of scepticism. Many of those surveyed worried about drug toxicity, drug interactions, appropriateness of their therapies, and more. Doubt in the healthcare system, coupled with the underlying stigma and shame that South Asian communities hold towards mental health conditions, makes it all the more difficult to seek out help. As many South Asian languages do not have words to describe mental health conditions, negative terms end up being used in their place, increasing the shame around these conditions. According to a 2019 review, shame is deeply woven into the South Asian community and acts as a major barrier towards acceptance and treatment of mental health disorders. Stigma also creates a paradoxical problem: although South Asian cultures are largely collectivistic, the shame surrounding mental health is often so potent that any such problems become the individual’s fault. The effects of this can be devastating. Interconnectedness creates an erosion of the sense of self that is not particularly conducive to handling major stressors and mental health concerns.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health.”

Ultimately, these are only some of the barriers facing South Asian immigrant mental healthcare. There are countless other cultures and innumerable nuances that need to be understood in caring for their mental health. It would be impossible to expect public and clinic health providers to be well versed in the struggles of every community. The idea of culturally competent care—which refers to the ability of healthcare professionals to understand, respect, and interact with patients with cultures and value systems different from their own—recognises this. The core principle here is curiosity; healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health. Care must also be framed within the context of how the culture views Western healthcare as well as the stigmas it holds regarding not only Western medicine, but mental health overall. For an arena as complex as mental health, there are no clear-cut answers. Simply put, nuance is needed to fight our myopia when it comes to sensitive care in immigrant communities.

Gender inequalities and women's health in South Sudan

Aishwarya reveals the outcomes of a research study conducted in South Sudan, shedding light on the humanitarian response programme concerning COVID-19 and the floods, and their impact on women.

Content warning: this article mentions gender and sexual based violence

South Sudan is in a vulnerable position, as it has a low capacity to cope with the global COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic, in combination with existent poverty, high illiteracy rates, and an ineffective public healthcare system, has resulted in a battle in South Sudan for its people. Moreover, heavy rain, floods, waterlogging, and displacement have impacted rural communities in remote provinces in the Jonglei state. Floods have also caused shelter and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) challenges. These challenges are a key public health issue within international development, as they are part of the first two targets of Sustainable Development Goal 6 by the United Nations General Assembly in the year 2015.

While the world is battling with the deadly virus, people in South Sudan are grappling with floods and heavy rain. “We are more worried about lack of food than we are worried about COVID-19,” said a respondent from our project titled ‘Process Learning of Christian Aid’s DEC COVID-19 Appeal in South Sudan’. This article discusses our research, which sheds light on the humanitarian response programme to both COVID-19 and floods, and explores the response in the context of women’s needs specifically. The study aims to understand the role of local communities and marginalised groups in Christian Aid’s Integrated COVID-19 Response Programme. Additionally, it offers recommendations for long-term recovery actions. The research was conducted through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, along with household surveys in two provinces in Jonglei state, Fangak and Ayod.

Image credit: Unsplash

“While the world is battling with the deadly virus, people in South Sudan are grappling with floods and heavy rain.”

During these surveys, we were exposed to different risks that impact the lives of women in their communities, including patriarchal norms, lack of menstrual hygiene products, and the collapse of WASH facilities. These examples illustrate that the humanitarian response needs to take gender dynamics into consideration in order to implement equitable and effective programmes.

Gender

Food is crucial to communities, yet the process and responsibility to obtain it is dictated by patriarchal norms. Women in these communities, known as Neur, are imposed with the responsibility of bringing food to the plate under any circumstance. While the entire community is submerged under water due to floods and waterlogging, food accumulation becomes a tough task for everyone—not just women. Men expect women to look after “the food aspect” because according to them, they are usually “far away from home” to “earn money” or to let the cattle graze. Women tend to pick water lilies, weeds, and water grass from the swamps, and convert them into flour by drying and grounding, providing food for their families. They are also responsible for catching fish from the flood water, which are boiled or made into stews. Unlike men, who tend to have equipment for farming and cultivation, women have nothing of the sort and usually use what they have available, such as their bare hands and their clothes. According to female respondents, they use their frock or clothes to catch fish while squatting in the swamps.

The health outcomes observed from these practices include skin infections, vaginal infection, and skin rashes—attributable to the unhygienic flood waters in which they sit for prolonged hours to hunt food. In our household survey, 95% of the total respondents were female. While interviewing them, it was evident that there are gaps in community participation and gender inclusivity.

In a further workshop that we conducted, participants shared that women in this community have no rights over their own sexual reproductive health, as they could not decide who they marry, or when they get pregnant. There have also been instances where a man rapes a woman and she is forced to marry the perpetrator. Patriarchal attitudes along with the flooding has led to destructive impact on the sexual and reproductive health of females in these communities.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Patriarchal attitudes along with the flooding has led to destructive impact on the sexual and reproductive health of females in these communities.”

Menstrual Hygiene

Menstrual hygiene emerges as a growing need—the survey shows that 60.1% of the female respondents do not use any materials for maintaining menstrual hygiene, while 17.6% use old clothes or rags as a substitute for sanitary pads. During interviews with several women in the community, the participants mentioned that they “let it flow” or simply “avoid going near men”, as they either don’t have access to menstrual pads or have not been informed about menstrual hygiene products.

“We do not have sanitary towels, most women here don’t even know what that is,” said a female member during a focus group discussion. In the survey, 41.4% of respondents viewed “talks on menstrual hygiene” as something that should not be publicly discussed. However, 23.2% suggested that if menstrual hygiene awareness was provided to their spouses as well, it could help them to handle menstrual hygiene “culturally and respectfully” within their family circles.

In the context of these taboos about public displays of menstrual hygiene, 40.8% of respondents stated that when disposing of menstrual hygiene products they “hide them away” from men instead of disposing of them in a hygienic manner. 25.7% bury them, while 12.8% “wash them for re-use” and 1.9% throw them away in open spaces. As such, sanitary products are seen thrown away in the flood waters.

While diving deeper into the challenges faced by women in the community on a day to day basis, it’s evident that factors like floods, rains, and waterlogging can’t be the only reason for these problems. Lack of community participation programmes by both the government or humanitarian agencies, and the absence of counselling and awareness programmes all contribute to a lack of knowledge. Female respondents stated that the presence of these might be useful to better manage their menstrual hygiene needs.

Collapse of WASH

The floodings have changed the dynamics of hygiene practices. Several respondents claimed that people in the community drink the same (flood) water that they defecate and bath in. Every situation here is connected to one another: lack of toilets leads to open defecation and lack of dry land due to floods leads to defecation in the flood waters. According to our survey, only 6% had access to a latrine. However, existing toilet facilities do not work, so most people continue to defecate in the open, usually in flood waters.

Image credit: Unsplash

In the absence of clean water for drinking and domestic use, people had no option but to use the logged water in front of their houses. There are limited practices of boiling or filtering water, so in most cases they consume or use it directly. This contributed to several water-borne diseases among people along with skin infections and Urinary Tract Infection (UTIs). In case of UTIs, people manage by “praying to God” for protection as they either shy away from seeking help or simply lack medical assistance.

COVID-19

Christian Aid in partnership with Africa Development Aid (ADA), a local Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO), implemented the DEC Coronavirus Appeal from August 2020 to January 2021 in these two counties. They aimed to increase knowledge amongst communities and healthcare providers on protection from COVID-19. Moreover, they focussed on improving the negative economic impact of COVID-19 on household food security and livelihoods.

To advance preventive actions against the virus, the project partners established 100 handwashing stations in Fangak. However, during our household survey, it was found that 93.1% did not have access to hand washing stations. Instead, 36% of people used ash or mud and 50.3% flood water to wash their hands, while only 13.7% used soap to prevent COVID-19 infection. During the interviews, respondents explained that soap was either stolen or out of stock. Moreover, in many cases, these hand washing stations were located far away from people’s homes.

Like one of the key informants said in an interview, “Flooding, hunger, health care, clean drinking water, and toilet facilities are the highest gap and urgently need a response”. Indeed, our findings suggest that the humanitarian response programmes should address these multiple risks and needs at the community level, including shelter, water and sanitation, menstrual health, gender-based violence, and education. Lastly, there are gender dynamics and traditional roles for women and men which should be considered when making equitable and responsive future programmes. Humanitarian response programmes and governments must work together to equitably and effectively improve facilities in these communities through conscientious attention to women’s needs.

“There are gender dynamics and traditional roles for women and men which should be considered when making equitable and responsive future programmes.”

The evaluation work discussed in this article was conducted by Environment Technology Community Health (ETCH) Research Consultancy, India. Special thanks to our partners in this project: Christian Aid (UK), Africa Development Aid (ADA), and everyone involved on and off field, amid floods and pandemic.

The black maternal mortality crisis: it’s her problem, it’s your problem, it’s our problem

Oluwaseun reflects on the black maternal mortality crisis in the UK, arguing that to end this injustice we must all evaluate the presumptions and misconceptions that lie behind these statistics and within ourselves.

Content warning: This article explores themes of racism, trauma, and death

Black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth or pregnancy when compared to their white counterparts in the United Kingdom (UK). Last year, that number was five.

As a black woman, I can’t help but feel sickened and exasperated when I see these figures. Why are the odds against us? Is anyone ever going to treat these deaths like the epidemic it is? Is anyone truly willing to address the root cause of this issue? These statistics are not just an unfortunate thing that is happening to people; they are the result of repeated and grave injustice against black mothers, black futures, and black families. Are we going to keep being comfortable with this atrocity?

“These statistics are not just an unfortunate thing that is happening to people; they are the result of repeated and grave injustice against black mothers, black futures, and black families.”

Image credit: Unsplash

Every story I read of traumatising birth experiences, and in severe cases, death, echoes a sentiment that is known all too well by black women: covert dismissiveness, blatant accounts of stereotyping, and a sense of invisibility to others. Behaviours like these have names that, unless spoken of, are perpetuated by ignorance: microaggressions and systemic and cultural racism. Microaggression is “a term used for commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, or environmental slights, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes toward stigmatised or culturally marginalised groups.”

Microaggressions often manifest as backhanded compliments and subtle insults. For instance, black women are often referred to as ‘strong’. Whilst this can be regarded as a compliment to some extent, it is frequently used in a way that denies expression of pain or concern. FixeXMore is a grassroots organisation committed to positively changing the birthing experiences of black women and birthing people in the United Kingdom. Annabelle’s story is one featured on FiveXMore’s blog, and illustrates the harm that these types of microaggression cause. After having a Caesarean section, Annabelle expressed concern about how well her scar was healing, to which midwives responded that it was “fine”, and they were “amazed by how well it had healed”. She discovered that her scar was in fact infected after taking herself to hospital. Whilst these midwives may have had very little experience with black skin, as Annabelle acknowledges in her blog post, their dismissal of her concern and appraisal of her skin highlights the unconscious racial bias they may have been displaying. Other stories on the FiveXMore’s blog detail the ways in which microaggressions undermine the care and the needs of the people in question. These aggressions often leave individuals traumatised and tired; tired of advocating endlessly for things that should be a basic right. There is a perception that microaggressions are just people being too sensitive, but I believe these microaggressions matter and that they are a big deal.

“Cultural differences and racial biases act as barriers for black people to access health care and to be seen, heard, and understood by healthcare professionals.”

Accounts like these are not limited to black women’s birthing experiences. Microaggressions are seen in differential treatment of members of the black community in the workplace and healthcare settings. Cultural differences and racial biases act as barriers for black people to access health care and to be seen, heard, and understood by healthcare professionals. These biases explain why black people are four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act, but less likely to receive support and adequate treatment. Sickle cell disorders, which affect approximately 15,000 people in the UK, are predominant in black African, African Caribbean, Mediterranean, and populations of Asian origin. Despite their prevalence, these disorders receive 30 times less funding than cystic fibrosis—a disease which affects around 10,000 people in the UK. The racial disparities in medical research can be attributed to systemic racism which, contingently, negatively impacts the quality of care sickle patients receive. Several factors contribute to the disparities listed above. However, figures repeatedly show that systemic racism is at the centre of the issue. Avoidance of the subject, lack of action, and persistent failure to acknowledge the ways in which people who benefit from the system do so at the expense of others, are all reasons why being a sick black person or pregnant black woman is a dangerous state to be in.

Image credit: Unsplash

Unfortunately, this is not a problem that is unique to the UK. In the United States, black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy and childbirth related complications. Cystic fibrosis affects less Americans than sickle cell disease but receives seven to eleven times more research funding per patient—findings which mirror those in the UK.

It breaks my heart to say that there is an insufficient amount of research on this topic and that there are no policies in the UK that protect and support black mothers. Maternal care is available locally for women across the UK, and there are mainstream initiatives, such as Better Births, which seek to improve birthing experiences and support women. However, there are few initiatives tailored to black women. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Care Quality Commission conducted an analysis which resulted in the launch of a programme that aimed to reduce the risk of Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) mothers contracting COVID-19 and suffering further adverse health complications. A continuity of care plan, which is targeted at women from BAME groups and women living in deprived areas, has also been set up by the National Health Service (NHS) as part of their long-term plan in effort to improve quality of care and reduce preterm births and perinatal mortality. Additionally, a petition launched by FiveXMore’s co-founders, Tinuke Awe and Clotilde Rebecca Abe, has invoked a series of governmental action points. The proposed government action and programmes are steps in the right direction, but must be taken forward to provide support black mothers.

I do hope for one thing in the fight for better maternity care for black women: a culture shift. Systemic and cultural racism has been highlighted as the overarching contributor to multiple racial disparities in healthcare and in wider society. Laws, processes, and cultural norms in the UK that benefit white people have damaging implications for members of the BAME community. I personally believe that new policies and programmes will not address the full picture unless they embody an active effort to dismantle and remove the conscious and unconscious biases that have given room for issues like this to exist. We must address the risk factors and contributing factors that lead to the death of black mothers, and we must make every effort to fund research to improve this. But it is imperative that we look at ourselves first. We cannot continue to make presumptions that black women and black people are more likely to be front line workers and come from overcrowded households without acknowledging that societal constructs have routinely placed BAME members at a disadvantage. We cannot conclude that black women are more likely to suffer from pregnancy related complications, and assume that this is enough to explain these statistics. We must think why, and consider why we have not thought about the why before. We must try to understand black women, let them be seen and heard, and admit when we don’t understand so their care can be better informed and refined. It is not enough to put policies in place when they have often marginalised black people; cultural reform is needed.

“For the sake of black babies, the black futures that blossom as these children grow, the black women and futures that we have lost at the hands of this: we must protect black women.”

The generation of women after me must not cry the same cry of injustice. The generation of women after me should not have to endure the fear of being invisible, misunderstood, and ignored. They should never have to subject the trauma of a preventable negative birthing experience. These figures will continue to add to the racial biases that black women face if we do nothing. For the sake of black babies, the black futures that blossom as these children grow, the black women and futures that we have lost at the hands of this: we must protect black women. We must design systems that support and benefit them, and, as a society, we must uproot all barriers opposing this. This epidemic has to end with our generation. We need to treat the current status of black maternal mortality like the crisis it is—childbirth should never be this dangerous.

The author recognises that not all black birthing people identify as women and mothers. Along with Oluwaseun’s reflections as a black cis woman, more research and voices are needed on the experiences and injustices of black trans people and folks across the gender binary, too.

The following websites offer resources to support black mothers and mothers-to-be, and BAME members with their mental health:

Black Mums Matter Too: A community for black mums and mums to be.

Black Minds Matter: Free mental health services for black individuals by black professional therapists.

Therapy for black girls: Wellness, resources, and therapists for black women.

‘The second sex’

Tamzin Reynolds explores the consequences of a world designed for the male body on women’s health outcomes.

If you are a woman, the chances are you’ve felt othered at some point in your life. I encountered it in the gym again the other week: whenever I go to a new gym, I’m faced with machines not built for me—a non-disabled cis woman of average height. The machine handles are often too thick for me to use comfortably (women’s grasp and wrist strength ranges from 50-60% of men’s). My arms aren’t long enough to use the bench press comfortably, and my feet don’t touch the floor on some machines. Yes, I can buy wrist straps and use alternative exercises to sort this out (as my male friend kindly reminded me), but why should I have to?

“Why do women have to change themselves?”

Image credit: Unsplash

My gym gripe may appear trivial, but other male-default designs have more serious impacts on health and wellbeing. Simple everyday examples include seat belts which don’t sit comfortably across women’s chests and other car design flaws resulting in women being 47% more likely to be seriously injured, and 71% more likely to be moderately injured than a man. Other examples include Personal Protective Equipment, which makes going to the bathroom a major operation, and police body armour, which doesn’t protect women because it isn’t made to fit their bodies.

In 1949, French feminist and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir wrote, “The lives of men have been taken to represent those of humans overall”. This famous quote from her essay The Second Sex still perfectly encapsulates this feeling of ‘otherness’. From small design flaws that make you feel like this world isn’t quite made for you, to the glaringly obvious discrimination all over the world, women suffer at the hands of bad design and the systematic ignorance of their experience.

But what does this mean for health? In a world designed for men, does women’s health suffer? The short answer is yes. From more obvious discrimination to daily microaggressions, the systemic otherness of women materialises in poorer health outcomes.

Image credit: Unsplash

“In a world designed for men, does women’s health suffer? The short answer is yes.”

In almost all parts of the world, women have a longer life expectancy than men; in the United Kingdom (UK), women’s life expectancy at birth was 83 years, while men’s was 79 years in the period 2018–20. Yet women also spend over a quarter of their lives in disability or ill health, while the figure is only one fifth for men. These figures translate to women in the UK living with ill health or disability for over five years more than men, and this gap is widening. The reasons behind this disparity are multifaceted and wide-ranging. Some, however, are remarkably simple and, therefore, surely simple to fix.

Until recent years, there has been a prevailing perspective that the only difference between men and women is size: that women are just ‘small men’. This perception has resulted in women being vastly underrepresented in research, which has serious impacts on health.

A 2008 analysis of textbooks from some of the most prestigious universities in Europe and North America found that male bodies were used three times more than female bodies to represent ‘neutral’ body parts. Caroline Criado Perez’s 2019 book Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men shone a spotlight on the degree in which the world is manufactured for a male prototype. This assumption of female bodies being ‘essentially the same’ as male bodies persists to this day, and it is dangerous. Although studies have found female representation increasing over time, the trends are modest and unlikely to resolve the wide gaps in research. For example, examining the 25 most-cited cardiology articles each year between 1996 and 2015, the percentage of women included only increased by 0.29% each year, and still only sat at 32.2% of female participants in 2015.

“This assumption of female bodies being ‘essentially the same’ as male bodies persists to this day, and it is dangerous.”

Similar stories are seen with HIV research. Women represent almost half of HIV-positive adults in the world, yet within research conducted in the United States, women were represented in only 38.1% in vaccination studies, 19.2% participants in antiretroviral studies, and 11.1% in studies to find a cure. With these gaps, how can clinicians hope to understand why men and women have different experiences of HIV? A stand-out distinction, for instance, is that women are less likely to start antiretroviral therapy, often due to family commitments making appointments difficult, fears about pregnancy, or socioeconomic circumstances. Without accurate research, these simple features of a woman’s HIV experience cannot be addressed.

While gender differences in health research have only more recently entered public consciousness, the gender pay gap has had a longer history in the headlines. Worldwide, for every £1 a man makes, a woman only makes 77 pence, and, while this pay gap is slowly narrowing, the impacts of COVID-19 saw the forecast time taken to close the global gender gap increase from 99.5 years to 135.6 years.

Image credit: Unsplash

Globally, women do 75% of unpaid work (this includes tasks like housework and caring for children, relatives, and spouse’s relatives), spending almost triple the amount of time carrying out this work, often alongside full-time jobs. Yet, the work women do is fundamental to keeping the world moving; it is estimated that unpaid domestic and care work contributes between 10–39% of a country’s Gross Domestic Product and can add more value to the economy than the commerce, manufacturing, or transportation sectors.

Unfair and frustrating? Certainly. But how does this affect health?

Low control over one’s job and an effort-reward imbalance are known to increase stress, resulting in poorer health outcomes like heart disease and stroke. For women, whose ‘primary’ jobs are often unpaid care and work, one can see how the high effort and low reward would fit this model. Perhaps predictably, given the underrepresentation in research, there are few studies which look at how this model plays out for different genders, but those that do find poorer health outcomes for women.

Beyond the psychosocial effect of women’s unpaid work and its repercussions on health, having a lower income than their male counterparts results in health inequalities. Worldwide, women can expect to earn between 31 and 75% less than men over their lifetimes due to their unpaid work and other factors like inadequate maternity leave, male bias in pensions, and biased employment procedures. Wealth helps protect against life stressors. As women live longer than men, and are less able to accumulate wealth, it’s no wonder women spend more years of their life in poor health.

“Women can expect to earn between 31 and 75% less than men over their lifetimes.”

Image credit: Unsplash

What happens when being a woman intersects with other marginalised communities? When we consider this, de Beauviour’s quote could read: “The lives of straight, cis, white, non-disabled, young men have been taken to represent those of humans overall.”

While women are underrepresented in research, this is even more true for women of colour, older women, women of child-bearing age, those with disabilities, LGBTQI+ women, and those of lower socioeconomic status. For example, in nail salons, where the workforce is almost exclusively female and often migrant (a population who often lack access to regulatory and health systems), workers are exposed to dangerous chemicals for long periods of time—the effects of which have not been researched by dose. This is not a problem women of higher socioeconomic status contend with.

In the UK, black women are five times more likely than white women to die in pregnancy or childbirth; an inequality which should not be tolerated, yet the dual evils of misogyny and racism (misogynoir) hinder change. Shockingly, a woman I know going through menopause told me how her general practitioner believed white women experience worse menopausal side effects. Do black women feel less pain, or are they given less attention and socialised to complain less, lest they be marked as an angry inconvenience? Evidently, more research on the menopause and female reproductive health is needed, and the inclusion of black women’s experiences is urgent.

A promising sign that change may be afoot came on International Women’s Day this year, when the UK government began a call for evidence for its Women’s Health Strategy. Submissions were invited from the public, clinicians, researchers, and groups interested in women’s health. The hope is that the government is finally addressing the historic difficulties women have had in accessing appropriate and adequate healthcare. The challenge will be to make sure positive change is effected across all groups of women.

“The challenge will be to make sure positive change is effected across all groups of women.”

More broadly, artificial intelligence (AI) may play a part in driving change. We’ve seen that when AI is trained on data which doesn’t consider the female experience, it only expands inequalities. But perhaps the rise in Femtech (female technology, a term applied to a category of software, diagnostics, products, and services that use technology to focus on women's health) will provide a partial solution to this—most likely in the areas of fertility and fitness for which apps and devices are commonly designed, providing women with the knowledge and control of their bodies that they deserve. There are, of course, concerns about data sharing, and care must be taken not to profit from an individual’s data without consent. Additionally, there must be a recognition that data harvested in this way is not concentrated on only women with more social privileges.

Ultimately though, we need more women in positions of power and influence, from a diverse range of socioeconomic backgrounds and cultures, more women engineers designing our world, and a general shift in the default men mindset. Women make up half the world; let’s have them shaping it accordingly.

The author recognises that statistics and discussion on women’s and men’s health represent a (cis)gender binary, and do not fully encapsulate the experiences of transgender, non-binary, and folks across the gender spectrum. Along with Tamzin’s own reflections on women’s health, more voices from marginalised genders are needed to deconstruct the white, cisgender, able-bodied, male norm in health research and care.

How the "menopause is natural” narrative is a damaging one

Aishwarya explains that discussing menopause as a natural phenomenon perpetuates social and health inequities, leaving women to push through their symptoms alone without practical and effective health advice.

If you Google menopause, a long list of symptoms appears. There may be a mention of how menopause symptoms are unique from person to person and advice not to take the list of symptoms at face value. But that part may be skipped over, leading straight into a paragraph on hysterectomies and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). This paints menopause as a well-structured process with simple solutions. It was only when I began to search for research papers on menopause in India that I uncovered a glaring problem: in conversations about menopause, authentic experiences had been left out completely.

Image credit: A. Krivitskiy via Unsplash

“In conversations about menopause, authentic experiences had been left out completely.”

Menopause is the one-year anniversary of a person’s last period. Since a person is born with a finite number of eggs in their ovaries, at a certain age, usually between 35 and 55, the number of eggs reaches below a threshold. Oestrogen—the hormone responsible for retaining and maintaining this constant—begins to fluctuate from its cyclical nature. As oestrogen governs more functions than just the menstrual cycle, decreasing hormone levels also result in a spectrum of symptoms throughout the body. For example, oestrogen plays a key role in controlling body temperature, and a low oestrogen level can cause a sudden spike in body temperature known as a ‘hot flash’ or ‘hot flush’—a common symptom of menopause.

I decided to conduct my postgraduate research on menopause experiences of cis-women in India through qualitative interviews. My research asked: if women were reporting difficulty during their perimenopause (the 5–15 years of physiological changes leading up to menopause), were their negative experiences a result of not making use of the available medical facilities? Since COVID-19 had limited my sample to middle-class women with access to Zoom, my participants were all literate and had easy access to hospitals and gynaecologists. But by the end of the first interview, it was clear that I had a lot to learn. My ignorance stemmed from a combination of my own privilege, and my education: studying science had distanced me from social issues and structures. By the end of my 30th interview, I had uncovered just how entwined social and health inequities are.

One of the most common phrases I heard was “it’s natural”. While menopause is indeed a natural phenomenon—after all, periods do eventually stop—calling menopause ‘natural’ seems to be doing more harm than good. If women are not accessing health infrastructure, and if health infrastructure is barely covering (or over-medicalising) the menopause, a deep dive into the ‘natural’ narrative may uncover some truths about where these health gaps lie. In the words of the women themselves, here is why the concept of menopause as ‘natural’ is both born from social inequities, and why using it perpetuates health inequities.

Calling it natural is a coping mechanism caused by lack of support

“Natural actually sounds good but I wish it was not traumatic. Not painful. I wish it was like, once you decide you don’t want to have kids you switch it off and everything stops. That would be more natural for me.”

Image credit: Unsplash

A menopausal support system requires two systems, each depending on the other to be effective: the social system and the medical system. While good gynaecologists may be available, most menopause symptoms do not have quick fixes. Dr Shaibya Saldanha, a gynaecologist in Bangalore, India, stressed the fact that menopause does not need to be a medical phenomenon. At the same time, she made clear that a natural process does not mean one without dietary and lifestyle interventions. For example, during perimenopause, sleep should increase while the body adapts to hormonal changes. However, “Women normally run on six hours of sleep … .They close the house down in the kitchen and feed every single person who eats at different times. And then they go to sleep and normally they would get up at 5:30–6:00 and start the next day.”

Solutions may appear feasible—such as sleeping for longer or shifting household duties to another family member—but support is often lacking. In a culture where gender roles are so deeply ingrained, social inequities play a role in menopause experiences. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic added to the workload of urban women, and this stress alone could have increased hot flashes and emotional fluctuations. Further, stigma surrounding menstruation continues into menopause. In some interviews, the women were unable to explain their menopause symptoms to their husbands because they had been discouraged from talking about their reproductive health during puberty.

This combination of shame and the lack of support at home leads women to use the word “natural” as a way of sweeping their health under the rug. If their health is not taken seriously then it must be unimportant, and most bodily processes that aren’t given attention are natural ones. Thus, menopause and its accompanying symptoms, no matter how harrowing, must be natural too.

An ayurvedic doctor that I spoke to explained how she bridged this gap. When a menopausal woman enters her clinic, this doctor ensures that either the husband or another family member is present during the consultation.

“Everyone takes doctors seriously and our word weighs. That extra step in counselling makes a big difference in fighting stigma.”

Image credit: Unsplash

Natural processes are common, and therefore you will manage

“Once [women] speak to their family they are ridiculed. Women of our generation are convinced, and it is very unfortunate, by women themselves. By women of the previous generation. They themselves say, ‘Oh you take this all so seriously, it’s very natural. You make a big deal out of nothing.’ Mind you this is not said by men. This is said by previous generation women. They are the ones who find it ridiculous.”

Two generations ago, treatment for menopause did not exist, nor did women have access to healthcare facilities. Tasked with running a household, women put their own health last. Along with the stigma surrounding menstruation, women had no choice but to manage their menopause alone. One of the most important long-term effects of the change in oestrogen level is a decrease of calcium uptake in the body. People going through menopause are encouraged to increase or supplement their dietary calcium intake so that postmenopausal concerns such as osteoporosis and arthritis are prevented. Unfortunately, rather than appreciating the availability of medical advancements for their daughters, women often look down upon other women who seek medical assistance. Silently suffering is seen as a display of strength: “We never used to complain about our cramps,” becomes “We never went to hospitals”. The prevalence of osteoporosis and arthritis in this generation shows just how damaging social inequities can be for health outcomes.

Image credit: Unsplash

Women’s health doesn’t warrant relevant medical attention

“We have a doctor but we don’t go much to the gynaecologist because it [menopause] is a natural process.”

Both postmenopausal women whom I spoke with regretted not having a check-up at the gynaecologist’s office. Yes, menopause is not a disease and nor is it a disorder, but, at the very least, a blood test to ensure that calcium and vitamin levels are normal is a must.

But the narrative around women’s reproductive health has always been ‘to manage’. Menstrual cramps in the middle of a class? Keep your head down and power through. A miscarriage? You’re shooed out the hospital door and expected to deal with the trauma on your own. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome? Despite it becoming an increasingly common condition, there is little progress in medical care provision. You’re handed a set of birth control pills and told to manage the side effects. Similarly, self-managing your menopause transition is the expectation. In fact, a woman who did seek medical help was dismissed by her gynaecologist who said, "Menopause is a part of life that everyone manages through.”

When it comes to menopause, unless your symptoms can be treated by medical intervention, there’s no space for a person going through menopause to seek guidance or support. “You have to stop everyone from removing your uterus,” was a common sentiment heard during my interviews with women. Instead of broadening the kind of support a medical environment can offer, menopause is medicalised and the fear of having unnecessary tests or operations prevent women from going to hospitals. Dr Saldanha told me frankly that there are only a few gynaecologists that sit menopausal women down and explain the practical lifestyle changes they can make to ease their symptoms. She had completed a one-year counselling course specifically so that she was better equipped to help the menopausal women who walked into her clinic. However, this kind of menopause counselling does not commonly feature in medical school curriculums.

Image credit: Unsplash

The lack of menopause education in medical schools because it is a natural process

“And I think that’s the nuances of medicine that is not taught to any of us as doctors. Beyond health; the needs of people. What about preventive health, what about a step beyond that?”

Menopause counselling sounds like a tall order, considering how menopause itself is barely covered in the MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery). Five women interviewed were medical professionals and they were all disappointed by the lack of menopause training. Public health tends to focus on the prevention of disorders, diseases, and ailments. Although menopause should not be looked at through any single lens, public health education and health promotion should encompass menopause. When discussed, menopause is also primarily and problematically grouped under ageing concerns. The average age of menopause in my study was 47, and women reported feeling disconnected with the concept of menopause being a sign of old age. Generations ago, menopause may have come towards the end of life, but lifespans are longer than they have ever been.

Image credit: Unsplash

“I don’t want to have one foot in the grave. I am working, I actually started a new academic program just this month. I don’t think of myself [as at] that age… It doesn’t have to be a natural part of the end in life. It’s going on while life is also going on.”

Rather than finding an answer to where and how menopause should be taught, it’s skipped over altogether, with medical colleges teaching a slide or two at most. This has led to many medical professionals not knowing what menopause symptoms are at all. Since the onset of perimenopause is unpredictable, women often visit a general practitioner first for their menopause symptoms. Unfortunately, many women in my study consulted multiple doctors before the word ‘menopause’ was even brought up.

How do we remove these systemic health and social inequities?

One of the most important things that I learned through these conversations is that ‘natural’ does not necessarily mean a ‘good’ thing. Although the menstrual cycle is a natural process, its stigmatisation turns it into something negative. On the other hand, the perception that everything “God-given” or “natural” has to be good prevents women from seeking help when a natural process doesn’t feel good.

Public health systems need to take the initiative to spread menopause awareness, and doing so should involve those who will not experience menopause too: de-stigmatisation begins with open conversations. It is thus imperative for menopause counselling to be a part of every gynaecologist’s training. Considering that menopause can intensify mood swings and lead to depression, “removing the uterus” should not be the only intervention that gynaecologists are equipped to provide. Validation is an important and missing component. All of the women who had negative menopause experiences thanked me for simply giving them a space to share what they had endured. Because of health inequities, doctors did not give them a safe space or the time of day to allow them to share their trauma; and because of social inequities, they were unable to openly discuss the negative aspects of menopause at home. A combination of more research and counselling would help to validate that what is natural is not always good. More often than not, women understand that they will have to push through their symptoms; they also want proof that what they’re going through is indeed natural, and that it is okay to not enjoy it.

Image credit: Unsplash

Menopause is something that cannot and should not be generalised for all. If the person makes the choice to seek medical support, infrastructure and solutions should be available. If the person decides to go through the menopause symptoms without any medical intervention, social systems should be available to support them. Most importantly, strengthening both social and health structures will allow people going through menopause to be able to rely on both. With neither system currently making space for menopause, the word ‘natural’ has become synonymous with ‘isolated’. Women deserve more.

“Menopause is something that cannot and should not be generalised for all.”

So close … yet so far

Snehal discusses the harsh realities of the COVID-19 pandemic that are often overlooked and underreported. Reflecting on the death of a family member, Snehal demonstrates the dire need for increased availability of vaccines and provision of healthcare services in low- and middle-income communities.

“Delivering vaccines to countries is only one obstacle; being able to administer these vaccines on the ground to communities with poorly resourced healthcare is another obstacle altogether.”

Image credit: Unsplash

The last two years have been the most challenging medically and socioeconomically in recent history, leaving an extensive impact on global healthcare systems. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the death of over 5 million people so far—and this number continues to rise. The impact this disease has had on people directly and indirectly means the world can never be the same again. As a doctor and frontline healthcare worker myself, the pandemic was a momentous challenge to say the least. But my life turned upside down when my beloved father tested positive for the virus on 31 December 2020. After being admitted to the intensive care unit, he was put on a ventilator for 13 days, and sadly lost his life on 27 January 2021. Being only 63 and physically fit, with no underlying medical conditions, my understanding remains clouded as to how this disease affected my father so severely. Yet we are only at the tip of the iceberg, and still attempting to make sense of how this disease affects certain individuals more seriously than others.