Trauma construction and traumatic events

In the first part of their essay series on cultural psychology, Kate and Mohammad draw attention to Dr Derek Summerfield’s critique of Western trauma narratives and reveal the limitations in our approaches to global mental health.

The era of white saviourism

Content warning: This article contains mentions of mental illness and racism.

In his groundbreaking work on decolonising trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in Palestinian territories, Dr Derek Summerfield calls for the reform of the treatment and overmedicalisation of mental health, particularly in humanitarian circumstances. The following two-part essay series understands trauma, in line with Summerfield's arguments, to be a condition manufactured by Western psychiatry, whereby the complex, unique, and often collective suffering of individuals is reframed as a technical problem to which short-term, individually-delivered solutions are applicable. In the second essay, the implications of Western framings of post-traumatic stress disorder will be explored further through the actions of non-governmental organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières. The series concludes by suggesting ways in which decolonising psychological care can improve inequalities in access to and treatment of mental health globally, as well as raise awareness surrounding the complexity of human nature and psyche.

Image credit: Unsplash

Western social constructions of trauma and traumatic events

“despite the fact that the diagnosis of PTSD was built from the specific experiences of male American veterans, its entry into the DSM-III meant that it became the definition applied to all, irrespective of culture, experience, background, ethnicity, or gender.”

Definitions of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first appeared in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). PTSD is described as “a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event” and is diagnosed through a series of DSM criteria, including “intrusion symptoms” like nightmares or flashbacks, and “negative alterations” in mood or reactivity like feelings of isolation and anger. The DSM-III and its subsequent versions (the DSM-5 being the most recent edition) are American-made manuals that have become used globally, supposedly offering a guide to psychiatry written in a “universal language for clinicians”. However, understandings of trauma were first premised on the early experiences of American soldiers returning from the Vietnam war in 1975. In part, the trauma experienced by these soldiers was given the label PTSD as a means to depict these soldiers as solely victims of the United States’ military establishment as opposed to individuals who had also perpetrated atrocities. In this case, the PTSD diagnosis legitimised the suffering of Vietnam veterans, and offered short-term relief to their distressing symptoms. Yet, despite the fact that the diagnosis of PTSD was built from the specific experiences of male American veterans, its entry into the DSM-III meant that it became the definition applied to all, irrespective of culture, experience, background, ethnicity, or gender.

The diagnosis of PTSD has spread to all countries subject to Western imperialism. The transition of PTSD from its localised socio-political origins into ‘objective biomedicine’ demonstrates the power of colonial channels and Western ideologies. Temporally specific diagnoses of trauma that emerged during America’s war on Vietnam have been erroneously regarded as universal and context independent, and thus applied worldwide. Suman Fernando—a lead scholar in the correlation between mental health treatment and racism—describes this as an imperialistic process: Western powers “marginalise other ways of knowing, destroy diversity, make alternatives to psychiatry vanish and create monocultures of the mind”.

“Temporally specific diagnoses of trauma that emerged during America’s war on Vietnam have been erroneously regarded as universal and context independent, and thus applied worldwide.”

How do Western conceptions of trauma engender inequality in mental health treatment?

In areas of conflict, Western non-governmental organisations distribute and deploy trained medical staff to deal with the fallout of violence and to treat early trauma signs. However, the deployment of medical staff trained in Western-centred psychiatric medicine in non-Western contexts is self-defeating. The challenge for Western medical staff is attempting to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to mental healthcare in individuals with symptoms unexplained or not understood by Western training. In taking such an approach, ownership of what is deemed important in traumatic events is transferred from those experiencing it to Western bodies deemed to know better, those “whose knowledge carries a stamp of authority”. The understanding of Western psychiatry as a globally-applicable science implies that the vast experiences of trauma survivors can be easily reduced into a single mental illness classification of “PTSD”. Thinking of trauma in this regard is simplistic, and invalidates the experiences of trauma survivors.

“ownership of what is deemed important in traumatic events is transferred from those experiencing it to Western bodies deemed to know better”

For example, on the premise of a PTSD diagnosis, many patients receive Western treatments such as counselling or medication, which “offer little in the way of alleviating the underlying causes of collective trauma”. Collective trauma refers to the “psychological reactions to a traumatic event that affects an entire society”. Acknowledgement of collective trauma is vital to validating the stories and emotions of survivors both before and during the traumatic events. By accounting for broader frameworks of “social justice, quality of life, human rights and human security”, a more nuanced understanding of the survivors' responses within the collective memory and experiences of their society can be gained, and adequate treatment provided.

“Western narratives arguably regard sufferers of collective trauma and psychological ill-health as passive bodies in need of treatment, as opposed to survivors with valid experiences.”

Furthermore, emotional distress experienced by survivors is generally hard to empirically measure in the categoric style of Western psychiatry—a limitation further exacerbated by a lack of cultural understanding. Deployed medics’ lack of knowledge or willingness to understand local idioms of distress leads to misdiagnosis and misinterpretation, pathologising of symptoms, and prescribing medication that is in some cases unnecessary and of little effect. Western narratives arguably regard sufferers of collective trauma and psychological ill-health as passive bodies in need of treatment, as opposed to survivors with valid experiences. This narrow understanding shapes and often rewrites the ways in which people view themselves as victims, which can worsen or complicate existing experiences of psychological ill health.

The dominance of Westernised trauma narratives is contingent upon the funding of Western psychiatric research and the value attributed to the Westernised methods, with very little insight into varied cultural understandings of trauma and the local idioms in which they arise. Studies that are academically and financially valued are those which underpin Western institutions’ own understanding of trauma narratives, thereby deepening Western-centric knowledge systems, while simultaneously excluding the experiences, symptoms, and accounts of trauma globally—a symptom of the colonial legacy in scientific research. With many international organisations prioritising Western-centric understandings of psychology, along with research funding being allocated to institutes mainly in the West, culturally sensitive research is excluded from international policies.

“Studies that are academically and financially valued are those which underpin Western institutions’ own understanding of trauma narratives, thereby deepening Western-centric knowledge systems, while simultaneously excluding the experiences, symptoms, and accounts of trauma globally”

For example, in tracing the history of Palestinian mental health diagnosis and treatment, Giacaman et al. emphasise the importance of “separating clinical responses to mental illness from the public health response to mass political violation”. It must be recognised that war and violence is a collective experience. Summerfield states that when witnessing the destruction of their social world, survivors lose embodiments “of their history, identity and living values and roles”. Therefore, to exclude such experiences, and to exclude context-specific socio-political understandings of trauma, can only cause further harm to survivors. The authors emphasise the need for a shift from the individual focus of Western medical indicators to broader global factors in trauma, such as a lack of human security and human rights violations.

In sum, the trend of excluding cultural contexts of trauma sustains global hierarchies. The West and “the rest” mentality reinforces centuries-old colonial structures and channels of power that depend upon stereotypes and generalisations. Such power imbalances result in an inability to reconcile different cultures, widens racial inequalities, and limits access to proper mental healthcare in resource-poor settings.

Western conceptions of trauma

In the second part of their essay series on cultural psychology, Kate and Mohammad take a closer look at the origins of international aid group Médecins Sans Frontières and discuss future directions for the continuing decolonisation of global mental health.

The case of Médecins Sans Frontières

Content warning: This article contains mentions of mental illness, racism, and discriminatory language.

Trauma projects and expeditions to ‘aid’ victims in resource-poor settings have become increasingly attractive and are fashionable for Western donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). However, the permeation of Western schools of thought surrounding trauma limits the degree to which the actions of these non-governmental organisations are effective or helpful. For example, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) deploys hundreds of their staff to conflict situations or areas affected by natural disasters. They have saved the lives of people worldwide, providing medical aid to all regardless of differences in their race, religion, creed, or political affiliation. Whilst MSF and their staff (from Western and non-Western countries) have shown courage and selflessness in their attempts to care for those most vulnerable around the world, their acts of goodwill do not come without criticism. This second part of this essay series will explore the extent to which NGOs are manipulating situations in areas of conflict and natural disaster by constructing trauma narratives as ‘epidemics’ in urgent need of attention to gain further donations, publicity, and resources. Lastly, we will explore the damaging consequences of being depicted as receptive patients or helpless victims by aid missions.

Image credit: Unsplash

Founded in France in the second half of the twentieth century, MSF is a private international association of doctors and healthcare professionals working to “provide assistance to populations in distress”. Despite their pledge to observe “neutrality and impartiality”, their humanitarian aim is deeply rooted in Western ideals of human rights. The rigidity of these ideals mean issues are framed and solutions are generated through the lens of colonial thinking. In the simplest sense: a humanitarian mission originating from a European country to help people deemed to be in need in Africa or Asia resembles colonial civilising missions. More specifically, in the case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), repetitive quotes in the media referring to trauma as the “hidden epidemic” likens the psychological condition to concrete communicable diseases capable of causing mass pathology. Framing localised trauma as Westernised conceptions of PTSD provides an incentive and authority for companies such as MSF to “resolve the issue”.

For example, the MSF handbook on refugee health makes claims that “20% of survivors of traumatic experiences will not recover without professional help.” Such language works to posit MSF as saviours and superior bearers of knowledge and healing, linguistically reflecting a “modern echo of the age of Empire when Christian missionaries set sail to cool the savagery of primitive peoples and gather their souls, which would otherwise be lost”. The colonial use of language was exemplified in the wake of the Rwandan genocide, when European NGOs sought out to make an early psychological intervention for the Tutsi refugees as a “preventative measure to thwart the later development of more serious mental problems,” inciting a sense of fear towards trauma and a need to “control the mentally ill of the global south”. However, the NGOs failed to provide adequate treatments, as concepts integral to the English understanding of trauma such as ‘stress’ and ‘family member’ were not translatable in Kinyarwanda and didn’t apply to Rwandan social contexts. As such, Western knowledge and its tools are incapable of identifying the expressions of trauma and the appropriate treatments cross-culturally. Further, such absolute depictions of trauma not only simplify it as a biological entity to be ‘fixed’, but pathologise human emotions and victims of traumatic events.

“Members and employees past and present of MSF made attempts to challenge their work environment through publishing of an independent report exposing the racism, discrimination, and abhorrent behaviours observed within the organisation.”

The white saviour complex at the centre of MSF's ideology is a symptom of a historical mindset that is accepting of discriminatory language and generalisations. Members and employees past and present of MSF made attempts to challenge their work environment through publishing an independent report exposing the racism, discrimination, and abhorrent behaviours observed within the organisation. As an employee of MSF relays, “I hear harmful generalisations and racist comments all the time when working internationally for MSF, from fellow international colleagues.” Employees went on to take note of their experiences in varied settings, stating they have overheard senior colleagues using hateful and ignorant language such as “These people aren't careful”, “They smell bad”, “People here can't figure it out”, “People here don't know how to do s***.” Yet the organisation's work sustains its faultless appearance, continuing to appeal to the Western eye and be championed for its exemplary humanitarian action.

“MSF joins many other Western non-government organisations in an inability to concede and amend their colonial history, address their white saviorism discourse, and dismantle their archaic protocols and procedures.”

MSF's exacerbation of white supremacy and neo-colonialism—the use of power by developed countries “to produce a colonial-like exploitation” and maintain control—are further evidenced within its division of labour: workers are split into both ‘international’ and ‘national’ categories, providing individuals in the same role with varied rates of pay and privileges dependent on their nationality and passport. Such divisions were described by MSF staff as "coded racialised language", with over 50% of its workers reporting experiences of racism. Since many ‘international’ workers depend on MSF for employment, it is hard for them to confront the administration and demand tough reforms for fear of losing their jobs.

Members of the organisation have made considerable attempts to stand against their work’s ethos, calling for MSF to look deeper into its history and what it represents, and demanding accountability for their harmful actions. Their stance is summarised by present MSF staff in the MSF dignity report published in 2021: it is impossible to view current activities and policies in MSF “outside the legacies of colonialism itself, from which MSF and the wider humanitarian sector grew, or contemporary power dynamics that maintain oppressions”. However, the impact of the report has done little to tarnish the reputation of MSF, or to change the lived experiences of both its staff and those on the receiving end of its ‘aid’. MSF joins many other Western non-government organisations in an inability to concede and amend their colonial history, address their white saviorism discourse, and dismantle their archaic protocols and procedures.

“the West medicalises and objectifies despair—responses to mass social upheaval, poor human rights, and diminishing social security—by categorising them into identifiable somatic symptoms”

The future of trauma narratives

“non-Western expressions of trauma are either falsely medicalised, untreated, misdiagnosed, or underrepresented, leading to inequalities in access to treatment for poor mental health globally”

To conclude, modern Western psychiatry and the clinical protocols and manuals that form it are based on biased Western research and experiences that are not inclusive of other cultural understandings nor the contexts in which mental ill-health arises. It is argued that the West medicalises and objectifies despair—responses to mass social upheaval, poor human rights, and diminishing social security—by categorising them into identifiable somatic symptoms. The 5th and most recent edition of the DSM has been criticised for its cultural bias and tendency to categorise all mental illnesses that do not align with Western understandings of psychology as “culture-bound syndromes”—that is, diseases or illnesses that are deemed to be specific to a particular culture or society. Subsequently, non-Western expressions of trauma are either falsely medicalised, untreated, misdiagnosed, or underrepresented, leading to inequalities in access to treatment for poor mental health globally. Implications of these discriminations bleed into the social lives of those afflicted and can have adverse effects on survivors. As Western diagnoses and understandings are prioritised, traditional coping strategies and idioms of distress are no longer meaningful to discuss patients' suffering, nor utilised as a common language for survivors, therefore exacerbating mental illness itself.

“The decolonisation movement emphasises the diversity of human experience, arguing that no single lens or methodology can encapsulate various understandings, ways of life, or experiences without falling into generalisations and omitting elements of people’s existences.”

To address colonial cycles in healthcare, critics are calling for a decolonised approach to psychology. A decolonised approach places human diversity as a priority in its thinking through actions like rewriting the curriculum used in medical schools to expand upon the limited Western frameworks currently used. The decolonisation movement emphasises the diversity of human experience, arguing that no single lens or methodology can encapsulate various understandings, ways of life, or experiences without falling into generalisations and omitting elements of people’s existences. In the case of NGOs such as MSF, training should be provided to inform their staff of the cultures that they work in. Learning about the ideas and practices intrinsic to other cultures would be a step towards acknowledging the gap between their expertise and those of local healthcare workers, community leaders, and healers. Culturally-cognisant work empowers locals to lead humanitarian agencies towards the concerns of their survivor groups, and guide them in understanding their way of life through respecting their rights, integrity, and traditional ways of coping.

‘Well at least my body is healthy’—a phrase not all can say when staring at their reflection

In this piece, Emma Roy explores the intersections between chronic illness and body image.

Many people, including myself, have had days where they stand in front of the mirror and aren't satisfied with their reflection. Perhaps they think their pores are too big, their waist is too large, and their muscles aren’t defined—they just don't like their bodies. When seeking support, many will turn to the advice of therapists, life coaches, and influencers and hear phrases such as, “You may not love the way your body looks, and that is OK—at least it is healthy!" and, “Honour your body because she keeps you functioning and does amazing things for you." or, "As long as you are healthy, you’ll eventually like what you see in the mirror; it just takes time." While most people can find encouragement in these mantras, what such phrases fail to account for are the perspectives of those with chronic conditions. What about the people whose bodies are failing or fighting them on a daily basis? Can they say those mantras when, to them, such perspectives just aren't true?

Image credit: Unsplash

From experience, I can tell you these affirmations don't always work. If anything, they can sometimes make things worse and leave me more frustrated with my body. My body is not healthy, and I deal with multiple chronic illnesses every day. I am just one of many who cannot repeat positive mantras in the mirror when dealing with chronic illnesses, and I've learned that that's ok. However, it has motivated me to explore current research and see what others who share my perspective are doing to cope.

“I am just one of many who cannot repeat positive mantras in the mirror when dealing with chronic illnesses, and I’ve learned that that’s ok.”

People with serious health conditions form a sizable demographic in the United Kingdom (UK). In 2019, approximately 18.8 million people over the age of 16 self-reported as having at least one long-term health condition. Among the younger populace, one quarter of 11–15 year-olds reported having a disability or chronic illness, while among 10–24 year-olds, one in ten felt that disabilities impacted their everyday activities. As for older members of society, it is estimated that by 2035, two thirds of adults over 65 are likely to have multi-morbidities. If you take a step back, that is about one in every four people in the UK who have something going on, visible or hidden, that seriously impacts their health. So, how do we—as people dealing with chronic illness(es)— try to address issues of body image? Am I the only one getting frustrated with my body, and tired of hearing, “oh well, at least your body is healthy”?

While the verdict is still out on body-positivity mantras, there is research available that explores the relationship between body image and chronic illness. Now, I want to be clear that just because someone has a chronic illness, or indeed illnesses, doesn’t mean they cannot love their body. I cannot speak for all, but I know that for many people in the chronic illness community it can feel harder to achieve body acceptance when they cannot rely on ‘at least’ being healthy. The World Health Organization found that the self-image and ego development of adolescents with chronic health conditions can be negatively affected, especially for those who score highly in verbal intelligence tests and have more severe diseases. Furthermore, the demands of chronic illnesses or disabilities, such as using body braces or managing medication, can negatively impact self-image. Virginia Quick builds on these findings by highlighting how chronic illness can place people at a greater risk of negative body image compared to their healthy peers, especially with illnesses that lead to weight fluctuation.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Chronic illness can place people at a greater risk of negative body image compared to their healthy peers.”

Although research on body image often focuses on young people, those of all ages can experience negative views of themselves. Young adults with bowel conditions recall being teased about their bodies, a possible contributor to their depression and anxiety. For people over 65, chronic illness can lead to a redefinition of self-concept that “involves the negotiation of identity trade-off as individuals confront their physical losses, [and] change their future goals.” This process plays out for people on medications, such as corticosteroids or insulin, that can alter the body and consequently affect body image. This was the case for me when I was going on and off various medications that caused visible puffiness and weight fluctuations; I definitely found myself looking at my body differently in the mirror. When such medications are needed to keep a patient stable, even if they try their hardest, those that take them may still find it hard to meet conventional standards of beauty. The appearance of research on body image and chronic illness is encouraging and I am hopeful that there will be more to come.

“Unlike the body positivity movement, which promotes the idea that everyone is beautiful in their own way, body neutrality focuses on accepting your body for how it currently is.”

I know I’m not the only person in England feeling distressed about my body image. Research aside, I wanted to see what others are doing to soothe their feelings and I stumbled upon the body neutrality movement. I learned that body neutrality can be a great asset in helping those with a negative body image, including those whose negative self-view intertwines with their chronic illness. Unlike the body positivity movement, which promotes the idea that everyone is beautiful in their own way, body neutrality focuses on accepting your body for how it currently is. Crystal Raypole describes it as “taking a neutral perspective towards your body … [and] moving away from the idea that you have to cultivate a love for your body or make an effort to love it every day.” This mindset can be especially useful for people living with chronic illnesses—sometimes you may not love your body and you shouldn’t feel shame about that. Raypole goes on to say that body neutrality is about respecting your body even if you don’t love it, and practising mindfulness as a response to how your body is feeling. Although the idea of body neutrality has been around for a long time, it’s something that I’ve only recently introduced to help combat the self-image issues related to my chronic illnesses. I’ve started to create my own mantras and see body image through a different lens. Plus, I’ve come to understand that whilst it might not feel like it sometimes, many people, chronically ill or not, struggle with body image. Overcoming this struggle is an effort that needs to be taken one day at a time.

Metamorphosis

This poem is about the poet’s grappling with their gender presentation as a non-binary transgender person, particularly their decision to go through hormone replacement therapy or not. While large biological changes can be intimidating and frightening, they’re equally natural, beautiful, and transformative.

This poem is about the poet’s grappling with their gender presentation as a non-binary transgender person, particularly their decision to go through hormone replacement therapy or not. While large biological changes can be intimidating and frightening, they’re equally natural, beautiful, and transformative.

Image credit: Unsplash

All my friends got top surgery this year, and I think I understand

The need to find a permanent kind of remaking: to stretch the clay,

Wield shape in the intention of hands building. I am afraid to be my

Own Creator, let the masculinity drip off me like water, let my hair sprout

Beyond its harvest. Maybe the collapse comes before the expanse,

Maybe home is only made known through its absence. What I do know is

Something is eating me alive from the very guts of my frame and I am

Still here. I am trying not to build a gender out of mirrors, or belonging

Out of needles, know the seed needs to crack before the bloom. Bursting

Into becoming is indulgently natural, peacock feathers splayed, lion's

Mane kind of extravagant. For now, I stare at a magnified reflection,

Tweezers in hand. Shaky fingers pluck at the black roots, exhaling cobwebs

Out of my ribcage. I do not think belonging is a place, but it took a crash to

Make a universe, home exploding into being where there was once only void.

I am still reaching in dark, waiting to sink my teeth into the someone I could

Become. I think conservation only dreamed in white imaginations, the rest

Of us know the warmth of entropy, of always being undone, the light of tidal

Shifting, crystal refractions of all the colors we have yet to dream. I am

Threadbare and breaking, cutting loose all that makes me smaller.

I have been small for long enough.

Cancer survival: due to patient or healthcare system characteristics?

Matthew argues that rapid cancer diagnostic pathways must be equally and proportionally accessible to all patients in order to close the deprivation gap in cancer survival rates.

Cancer survival is improving and has doubled in the last 40 years in the United Kingdom. However, the increase in survival has not been the same for everyone: it is leaving behind those who are more deprived.

Figure 1: Five-year relative survival (%) by deprivation category (detailed later) and calendar period of diagnosis in England and Wales. Relative survival, or net survival, is the survival probability derived solely from the cancer-specific hazard (risk) of dying and is independent of the general population mortality, i.e., competing risks of death.

Figure courtesy of Bernard Rachet, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

Until the early 2000s, less than half of people diagnosed with cancer were expected to live for five years. Since the introduction of the National Health Service’s (NHS) Cancer Plan in 2000, cancer survival has rapidly increased. The NHS Cancer Plan, and successive cancer policies, recognised the importance of an earlier diagnosis on the chances of a good prognosis. Thus, there was a greater drive to increase the proportion of patients diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Over the past two decades, the proportion of patients having their cancer detected earlier has dramatically increased, contributing to the rise in cancer survival. This trend is in large part due to factors such as awareness campaigns (e.g., association of smoking and risk of lung cancer), cancer screening initiatives (e.g., checking for lumps in breast cancers), and advancements in treatments and technology (e.g., positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans).

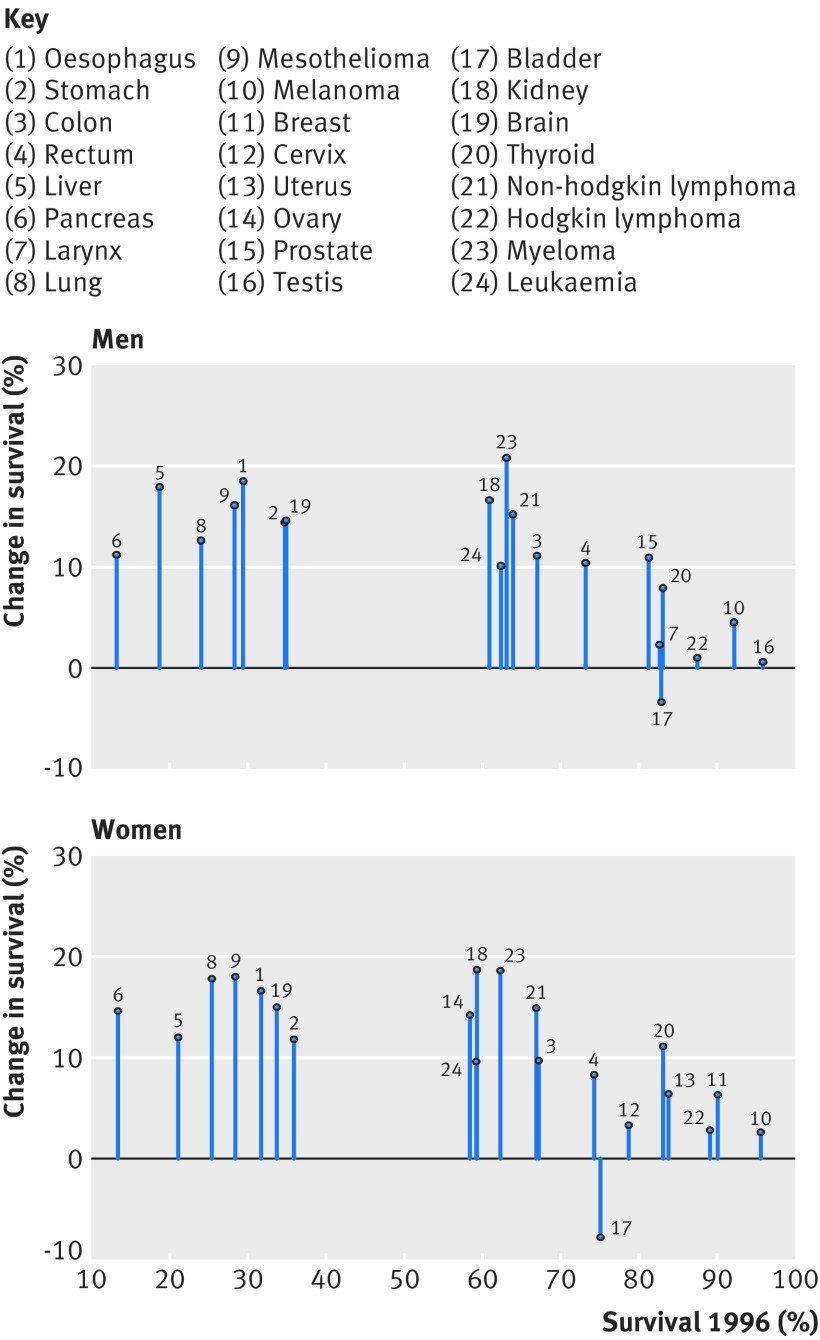

Figure 2: Change in one-year net survival between 1996 and 2013 for 20 cancers in men and 21 cancers in women. For example, amongst women, patients with pancreatic cancer had the lowest survival in 1996 but survival increased by approximately 15% by 2013.

Figure courtesy of Aimilia Exarchakou, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

In population-based cancer survival research, the measure of deprivation has evolved from a composition of Karl Marx’s structural and Max Weber’s societal perspectives. It is defined as the socially derived economic factors that influence what positions individuals or groups hold within the multi-faceted structure of society. Deprivation is a contextual measure of not only income but of one’s opportunities within their immediate area that are identified by several domains (employment, education, etc.). An individual’s assigned deprivation level is determined by the rank of their area relative to other areas in terms of a weighted combination of the domains. Thus, an individual’s level of deprivation is (i) an ecological measure and (ii) relative to other individuals. The latter is an important characteristic to consider since the areas with lower ranks are interpreted as more deprived areas compared to areas with higher ranks: they are not necessarily all deprived areas.

However, for some cancers, survival amongst those living in least deprived areas has improved faster than in more deprived areas. In other words, an unexpected but obvious phenomenon has occurred: there has been a marginal increase in survival, but the difference between deprivation groups has grown wider. Amongst males, the greatest widening was observed for melanoma, prostate, colorectal, and haematological malignancies; amongst females, it was gynecologic cancers. What is less obvious but no less important is that, apart from lung and brain cancers, the deprivation gap for any cancer has not narrowed. The bottom line is that these cancer plans have not targeted all patients equitably; they have missed patients who are living in more deprived areas.

Reasons for persistent inequalities

Unless the deprivation gap in survival is addressed, these inequalities are expected to persist or even widen in some cases. Cancer survival is often described by patient characteristics, such as sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic level. This has contributed to a common public misconception that patients with certain characteristics are predetermined to have lower chances of survival; however, patient characteristics account for approximately only a third of the socioeconomic inequalities. In fact, most of the socioeconomic inequalities in survival are due to unknown factors (other than patient characteristics). Optimal interactions between the patient and the healthcare system around the time of cancer diagnosis can drastically increase a patient’s chances of a better prognosis. Such optimal interactions include: effective communication during a general practitioner (GP) appointment, distinguishing between comorbid and cancer-related symptoms, being referred from a GP to a consultant within two weeks, and promptly receiving the diagnostic test and results. The problem is that these optimal interactions are less likely to be experienced by those in more deprived areas.

The current framework for cancer diagnoses is the rapid diagnostic and assessment pathway, such as the colorectal cancer diagnostic pathway (Figure 3). The aim of the diagnostic pathway is to ensure patients receive the outcome of diagnostic tests within 28 days of referral. Indeed, reducing the time that a patient is on the diagnostic pathway will contribute to an earlier diagnosis. However, to be fully effective it is crucial that the diagnostic pathway starts when the cancer is in its early stages—in reality, patients may have cancer months before they have the consultation with a GP that initiates the pathway. The diagnostic pathway could be thought of as a product of a company that is accessible to those who can “afford” it in a society where the currency is “privilege of accessible healthcare services”. It is not the function of the diagnostic pathway that is systematically biased, it is inaccessibility that induces bias.

The diagnostic pathway is susceptible to two major flaws resulting from access: GP availability and testing capacity. Firstly, the number of GPs within any area must be proportional to the size and healthcare requirements of the population they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with less GPs may have a reduced chance of accessing the diagnostic pathway. Secondly, the number of specialists and the capacity of diagnostic facilities that feature along the pathway must be proportional to the demand of any area they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with unavailable diagnostic specialists or facilities will have a reduced chance of receiving a definitive diagnostic result (including earlier diagnosis) within 28 days of a GP referral.

Figure 3: Colorectal cancer rapid diagnostic pathway. (MDT: multidisciplinary team, GP: general practitioner, CT: computed tomography, OGD: gastroscopy, CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen test, CNS: clinical nurse specialist, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, TRUS: transrectal ultrasound.)

Figure courtesy of NHS Cancer Programme (NHS England)

To elaborate on the first flaw (GP availability), the number of GPs is not only lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, but there is an exodus of GPs across England, leading to a comparatively higher workload for GPs who do work in these areas. Moreover, GP time for each patient is, on average, lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, even for patients with comorbidities. This is an example of the inverse care law: those who most need care are the least likely to receive it. Higher workload for GPs, in combination with reduced GP time, increases the chances of missing ‘red flags’ of cancer symptoms. Furthermore, more deprived areas tend to be more densely populated and have a higher prevalence of patients with comorbidities. More densely populated areas are likely to have a healthcare service with a higher demand, leading to an increased chance of patients being diagnosed through emergency route, which is closely correlated to a later cancer stage at diagnosis. A natural, and foreseeable, consequence is a future with a reduced number of cancer patients from deprived areas on the diagnostic pathway, ultimately leading to the sustained deprivation gap in cancer survival.

Figure 4: Number of registered patients per GP by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in order of deprivation level.

Figure courtesy of The Health Foundation

To elaborate on the second major flaw (testing capacity), a key phase of the cancer diagnostic pathway is during Days 3 and 14 (the Straight to Test [STT] phase), when the cancer-specific test is expected to occur. One commonly required procedure is a computed tomography (CT) scan, which is carried out by a radiologist. The same issues around accessibility materialise again: not only is there a radiologist shortfall, but millions are spent on scan outsourcing. Some of the key findings of the Royal College of Radiologists’ (RCR) annual census (2020) were that the UK radiologist workforce is now 33% short-staffed, with a projected rise to 44% by 2025. Additionally, consultant attrition remained at an average of 4% within the UK. Previous data from the RCR highlighted that scan outsourcing in 2017 rose by 32% since 2016. The cost of scan outsourcing (paying private companies to help with the workload) was estimated to be £116m in 2017 (enough to pay 1,300 full-time radiologists). With no clear influx of radiologists, and an increasing demand for CT scan usage over the next few years, the deprivation gap in cancer survival is unlikely to narrow.

Reducing inequalities

There are multiple factors contributing to socioeconomic inequalities. However, increasing the NHS budget to improve the ratio of patients to GPs and radiologists would drastically reduce the deprivation gap in cancer survival. The healthcare system can only go so far as to be more efficient with the same budget; each year, there is a higher demand for additional services that heavily outweighs the annual increase of the NHS budget. Even advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis, comes with its own inherent inductive bias that may itself contribute to the deprivation gap in survival. Without the appropriate capacity for demand in the areas where care is most needed, it is unlikely that we will see a reduction of the socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival and the true potential of faster cancer diagnostic pathways.

The heroes we are not

Oluwaseun uses poetry to describe the frustrations and exhaustion that comes with being a frontline healthcare worker despite their bravery and commitment being celebrated by others.

Oluwaseun was inspired to write this piece after experiencing what it was like to work on the frontline with a tired team. She explores how when her colleagues and herself want to discuss issues that they face us as a staff group, people often make remarks that denies them a place to express their feelings in a safe space. This poem explores that frustration and the toll that it can take on already tired healthcare professionals, who really love what they do, but still want to be seen as people.

Image credit: Unsplash

Today, like any other day, I put my uniform on and wear the badge of hero, national treasure

The burden, the burden.

Has anyone stopped to look at the woman who wears the badge?

“I can’t be the only one”

I know I am not.

This hero, as human as she is, as every one of us is, chose to rise today

She chose to rise, work, and give.

I’m a little tired, but so is the woman who has been here for 8 hours with no answers in a room full of people she doesn’t know

“Am I carrying too much? Can I do more?

I wish I could I wish we could.”

We are all in this together; the comradery is incredible

I still smile and get excited at the thought of another day growing and serving

I still think it is a privilege

But my reserves are hollow barrels now

“We are very busy at the moment. I’m sorry it has taken so long for us to get to you”

I’ve said that too many times.

The woman, the man, the child, the being

They bring their fears here

Asking us to hold onto them with dignity and honour

I see them and carry them

But the problem is

I am human too

We all are

“We need to get this right and do better, we can’t have this for the patients”

That’s true,

You’re right but has anyone stopped to look at me? At all of us?

The people in the uniforms

We come with our perfectly flawed conceptions, personality traits, and tendencies

We come with our problems, our ideas, our brilliance

Our conflicts

We come with the wholeness of who we are

These things are what we serve with

Does anyone see that?

Image credit: Unsplash

We come with mistakes and through our reflections we rise up from them together

Is there any grace for that?

Is there any grace for the people who, with courage and limited resources, give?

Is this house still holding us?

When we pour out the maps of our minds and the burdens of our hearts will you still call us heroes?

Is there space for a garden to bloom?

I am like any other woman who chooses to rise and stand

Whether she is in a classroom, a home, an office or a business

I am not a hero; I don’t think I ever will be

If heroes are silenced when they protest and speak then I never hope to be that.

What I am is human

And, I will be that till the day I die.

And, what I put on is courage

I have seen the depths of what it means to be human in my uniform

In anger, in confusion, in sadness, in trauma

I have seen the rawness of it, its poignance

For that I will not be a hero

I will be a human, learning day by day, as I choose to wear my uniform.

Insects—can we stomach them?

In this article, Cherie draws on a provocative idea: insects as part of our diet? She navigates the intersections of culture, sustainability, and nutrition to help change our minds.

Insects are gaining attention as an alternative source of protein in the United States (US), Canada, and various countries within Europe. With a dry-weight protein level of 60%, insects are deemed by the Food and Agriculture Organization to be one of the most sustainable alternatives to animal-sourced protein. As global populations continue to grow, it is estimated that a 70% increase in agricultural production worldwide is necessary to feed populations around the world. This demand, coupled with the rising cost and consumption of animal protein, is both a strain on the environment and an exacerbation of existing food insecurity levels. With a much lower cost, strain, and impact on our environment, insects could be our solution.

Image credit: Unsplash

“With a much lower cost, strain, and impact on our environment, insects could be our solution.”

The consumption of animal-sourced protein is deeply embedded in Western culture through symbolic ties to wealth and, since the twentieth century rise of meat-production technology, a reputation for optimal nutritional benefit. The idealisation of animal-sourced protein, and consequential rejection of insect-based protein, can be traced to early European colonialism. European colonisers were introduced to the idea of insects as a food staple; however, rather than accept such alternative food practices, they took them as grounds to denounce the local populations. Colonialism served to establish social hierarchies that propagated the denigration of cultures who ate insects simply because the practices were different from those of the colonisers. This stigmatisation of insect consumption contributes to the common rejection of insects as food today.

“The idealisation of animal-sourced protein, and consequential rejection of insect-based protein, can be traced to early European colonialism.”

African and Asian cultures have long incorporated insects into their diets and continue to do so: indigenous communities like the Mofu in Cameroon and Bushmen in Botswana rely heavily on insects for protein, iron, and vitamin D; and street vendors in Thailand commonly sell insects deep fried on sticks or tossed in spices. Cross-national surveys conducted across 13 countries found large variations in the rejection of insect-based foods, with higher rates noted among older people and those living in Europe, the US, and Australia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a study comparing the attitudes of Chinese and German participants found greater acceptability of insect-based food, and willingness to consume it, among the Chinese population.

Some of this variation can be attributed to the fact that insects, in general, are more common in populations that live around the tropics. In such climates, insects are a more practical source of food due to greater variety and year-round availability. In more temperate climates, such as the United Kingdom, houses are weatherproofed to accommodate seasonality, shutting out insects and limiting interactions with them. Ecological differences thus serve as an additional barrier to broader adoption of insects as a food source; however, most change is likely to depend on societal acceptance, preference, and cultural shifts.

Despite research showing that insects are high in protein, nutrients, and essential minerals, many individuals fear the thought of eating insects. Insects are often referred to as pests and are perceived as contaminators of food, which, in combination with childhood experience, parental influence, and societal teaching, cement such presuppositions. Additionally, terms used to refer to insects—such as the French phrase ‘la bestiole’—carry negative connotations. Moreover, as a novel concept in most societies, unfamiliarity with insect consumption can cause hesitation.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Sensory stimulation and other hedonic aspects play a distinct role in dictating what is considered appetising—the presentation, advertisement, and texture of a dish is also important in creating a positive meal experience. The presence of visible insect limbs or bodies, and food texture that is slimy or mushy, can trigger revulsion, especially if individuals are relatively new to consuming insects as food. A natural distrust of new foods is one aspect of the omnivore’s dilemma, in which the need to consume new types of food for the sake of nutritional variety conflicts with the fear that foods could be harmful, toxic, or contaminated.

Ultimately, a greater acceptance and consumption of insects as food will only materialise once individuals recognise insects as a viable and sustainable food source. The omnivore’s dilemma remains a significant barrier, but efforts to change mindsets and increase desire for more sustainable food systems could be the key to this issue. Development in the formulation and processing of insects could help to mask their presence in familiar and conventional foods and promote more widespread use. Some examples include the use of insect flours; the addition of insects into processed foods, such as burgers; and the use of familiar flavour profiles in insect-based food products.

For most people, insects (like meat alternatives) are unlikely to replace animals as the main source of protein. However, arguably environmental benefits would be seen if the majority of the population were to eat insects in place of animal protein for just one day a week. While current demand for the use of insects as food is still low and mostly limited to the livestock industry, there are emerging signs that suggest a slow increase in acceptability. In Canada, locally-produced cricket powder is sold in the nationwide grocery chain Loblaws, and there is a dedicated aisle for insect-based products at certain organic stores in the US, indicating we are closer to incorporating insects into our diet than previously thought. Increasing acceptance and appreciation of the diversification of food sources could foster a pathway to decolonisation of cultural food norms, providing both nutritional benefit and improved sustainability of food systems.

Operation waitlist: barriers to life-saving surgeries

Rishabh breaks down the different barriers to care and explains how surrounding resources can influence surgical outcomes.

Even with the dazzling advancements in healthcare in the past 50 years, barriers to care seem to remain an unfortunate motif that stands in the way of improved collective health outcomes. Limited access to healthcare leads to suboptimal care for patients, which can carry serious consequences for some of the most acute cases—particularly those who require emergency surgical intervention. The conversation surrounding available resources and surgical outcomes is not a new one, and many of these disparities have been characterised over the years across various surgical subfields, from surgical oncology to paediatric neurosurgery. To make matters more complicated, the COVID-19 pandemic serves as an additional stressor and has compounded the strain on healthcare systems trying to meet the needs of their patient population.

Image credit: Unsplash

First, a number of pre-existing upstream elements can impede a patient’s ability to seek care. The social determinants of health are factors that include characteristics of a patient’s environment that may appear far removed from formal healthcare processes, but still significantly affect the patient’s health outcomes. For example, a patient’s limited access to nutritious food, clean water, education, and a safe living environment may predispose them to more serious conditions and complications in their surgical care than if they enjoyed unrestricted access to such resources. This too has been studied extensively, leading organisations such as the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States (US) to develop a myriad of programmes targeting the social determinants of health in underserved communities. Similarly, on the healthcare systems end, limitations in resources result in unequal outcomes. Rural and county hospitals experiencing personnel shortages, overwhelming demand for operative treatment, and limited financial assets, tend to fare worse than their counterparts in outcomes such as post-operative mortality. This is deeply concerning, given that rural and county hospitals often care for patients with more comorbidities and limited resources.

In the last year and a half, the COVID-19 pandemic has further strained an already stressed system in the US. As a result of personnel shortages, bed unavailability, and the precautionary delay of non-urgent operations, there is currently a significant backlog of desperately needed surgeries. Taken together, these factors have also led to the loss of revenue for academic and non-academic hospitals, jeopardising their ability to take care of patients in the future. Even so, the COVID-19 pandemic has not affected all hospitals equally. In the US, safety-net hospitals—which care for the uninsured and underserved—saw their profits dwindle, while their private counterparts experienced an increase in revenues. In part, this discrepancy is due to anticipatory financial planning by private hospitals, but it is also a result of the federal government’s pre-pandemic initiative to allocate relief funds to hospitals commensurate with their revenues. Additionally, because the safety-net patient population tends to be sicker, more vulnerable, and require more intensive resources, these patients have suffered disproportionately along with the very hospitals tasked with caring for them.

“Bridging the resource gap and the outcome chasm cannot be achieved in one day. Indeed, social inequities present barriers to patient care in healthcare systems around the world. ”

In response to this exacerbation of existing disparities, hospital systems around the world have taken steps to provide adequate care. After all, the consequences of complacency in the face of limited resources are dire. Backlog in the cancer referral pathway, for example, could cause a significant excess in death rates according to a study designed to measure the effects of delayed referral in the United Kingdom. To optimise resources, various techniques have been implemented to ensure surgical services can operate on as many patients as possible before their disease progresses. One such technique was deployed in a hospital in Hong Kong, which created a tiered system of cancer subtypes and assigned target completion times for the respective operations, leading to some alleviation of their waitlist burden. Furthermore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has provided guidelines for resource allocation and triaging systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. These guidelines help hospitals streamline their care so that they may treat as many surgical patients as possible given the realities of resource shortages. While endeavours such as these have eased some of the strain on healthcare institutions, systemic factors continue to unduly affect disadvantaged patients.

Bridging the resource gap and the outcome chasm cannot be achieved in one day. Indeed, social inequities present barriers to patient care in healthcare systems around the world. While steps have been taken to address these disparities, further investigation into potentially implementable solutions is more important now than ever. The goal of this pursuit is to ensure that all patients, regardless of their backgrounds or means, receive the surgical care they need.

Abortion law in context, from the perspective of a Texan

Kristen argues that a battle for political power and control lies behind the most recent abortion ban in Texas, and considers the implications of this for women and underserved populations worldwide.

Content warning: this article discusses abortion

Abortion is a touchy subject that can often elicit a broad spectrum of reactions, both from public health professionals and lay voters alike. An understood silence is even more real and raw in my home state of Texas, a place where abortion law has taken centre stage in a national debate about the role of religion in government, women’s rights, and healthcare quality. However, the pursuit of restricting women’s bodily autonomy is not so much a moral battle, as Texas legislators may like you to believe, as it is a struggle over a rapidly changing culture.

Image credit: Unsplash

When people ask, I like to describe Texas as a microcosm for all the political tension currently unfolding in the United States (US), not unlike trends in the United Kingdom (UK), France, and other countries. It’s a state that is rapidly expanding, diversifying, and simultaneously attempting to hold onto its identity. These themes appear to conflict many long-term residents, and a fierce defence of tradition, homogeneity, and intolerance has taken hold of a swath of voters. The most recent result of attempts to uphold reactionary values within the laws of the state is the Texas Heartbeat Act (Senate Bill 8), signed into law by the governor Greg Abbott on the 1 September this year, which bans abortions six weeks after conception. This bill is the most restrictive abortion law of the century, and openly defies the legal precedents set by Roe v. Wade in 1973 (a legal case in which the US Supreme Court ruled that a state law banning abortions was unconstitutional), limited though they are. Arguably, one of the most remarkable features of the legislation is that it relies on civil reporting to keep women in check, as opposed to criminal enforcement of the ruling.

Growing up as a woman in Texas has taught me many things. Chief among them is resilience, an appreciation for cultural diversity, and the belief that I can achieve anything with a hardworking spirit. However, the state’s restrictive laws placed on female freedom have defied these values, and mandated the loss of opportunity for many women, especially women of colour. Unfortunately, the novel abortion ban is one of several laws passed by the state government that reduces the freedom of its people. While the Texas legislature was drafting Senate Bill 8, it was simultaneously constructing regulations to restrict voting rights. Senate Bill 1, signed into law on 7 September, reduces the validity of mail-in voting, shutters 24/7 polling stations, and grants free movement to partisan poll watchers (volunteers who observe the election process) in voting locations. All of these restrictions target the novel initiatives developed by Harris County to facilitate voting in the 2020 presidential election. This encompassed the state’s largest and most diverse city of Houston and primarily impacted voters of colour. By passing both of these laws, Texas legislature has effectively revoked the legal rights of women of colour to receive an abortion, and to vote freely and easily.

“Texas legislature has effectively revoked the legal rights of women of colour to receive an abortion, and to vote freely and easily.”

While Republican lawmakers may refute their desire to dismantle the rights of minority groups within Texas voting pools, the restrictive abortion law currently in place is clearly not an attempt to protect unborn children. If that were the case, it would have been accompanied by sweeping child support mandates, day-care stipends, and mandatory paid parental leave. Furthermore, if the law represented the legislators’ belief that all life is sacred, they would be applying equally vigorous restrictions to gun ownership, eliminating the death penalty, and funnelling government funds towards public health measures and education. Instead, the highly religious language used to justify the ban is simply an attempt to consolidate power through the mobilisation of evangelical voters. The US prides itself on religious freedom, and reduced government involvement in matters that involve personal beliefs. However, when it comes to maintaining a significant portion of your voter base and eliminating the power of your opposition—anything is fair game.

Image credit: Unsplash

Because political complexity has created such tangible tension in Texas, it would be inaccurate to paint these events as straightforward racist acts against a large proportion of Texas residents, although their repercussions certainly have that effect. Rather, they represent the last dying breaths of a government that no longer represents the people. Texas republicans have played every move at their disposal to maintain power, including gerrymandering the most diverse portions of primarily left-leaning cities, passing the aforementioned restrictive voting laws, and mobilising evangelical values to support their claim to moral supremacy. However, Texas is changing, much like the rest of the world. The population is becoming increasingly youthful, and Texans of Hispanic heritage are set to comprise the largest demographic group in the state by 2022. These populations tend to swing left, a fact that was exemplified during the 2020 presidential election where only slightly less than half of the state voted for Joe Biden—the greatest turnout of blue votes since the state switched to red in 1980 during the election of Ronald Reagan. Reactionary representatives can see writing on the wall: it won’t be long before Texas becomes at least a toss-up state, much like Florida, where election turnover is high, and leadership is diverse.

“Restrictive abortion laws do not stand alone, and Texas’ inability to release its hold on women’s freedom is, in reality, an expression of a fear of change.”

Finally, the US Supreme Court—the highest court in the land—has done nothing to protect women and their rights against the draconian rules laid out within Senate Bill 8. Even though the court could choose to temporarily suspend the law while it considers the bill’s legality, a 5-4 decision permitted the ruling to move forward without challenge. Although it now appears the court will reconsider this position, and likely rule in favour of abortion providers, this slow action has left hundreds of women exposed to the risks of unsafe abortions and the “civil servants” hell-bent on reporting and punishing their private actions. I’m fortunate enough to now live in a country where abortions are safe and legal, but my heart breaks for other Texan women who cannot say the same, and whose government refuses to protect them. Restrictive abortion laws do not stand alone, and Texas’ inability to release its hold on women’s freedom is, in reality, an expression of a fear of change. Sadly, the reflections of a faltering democracy afflict not only Texas, or the US; Europe is well on its way to a political schism of its own. In what other ways will scapegoated women, minorities, and immigrants suffer? Illegalised abortion is simply a signpost on the road toward the erosion of human rights in the name of power.

Improving nuance in South Asian immigrant mental healthcare

Pallavi discusses the ways in which Western approaches to mental healthcare fail to recognise the nuances of immigrant communities, cultures, and conceptions of self.

If there is anything the pandemic has shown us, it is that isolation is exceptionally rattling. A June 2020 survey by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 40.19% of adults were experiencing depression, anxiety, PTSD, or substance abuse in the United States. This was three to four times higher than the rates reported just the year prior. Thus, the need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations. Yet, the diagnosis and treatments we assign to these mental health conditions often do not recognise nor appropriately address these differences. While there is some degree of universality in the human experience, there must be greater nuance and understanding in how we provide mental healthcare, especially in vulnerable and underserved populations. To illustrate this need, I will specifically be looking at how mental health is diagnosed and treated in the United States (US) and how this approach often does not work for the South Asian population here.

Image credit: Unsplash

“The need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations.”

The medical system in the US is ascribed by the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V). The DSM-V is a collaborative work created by mental health professionals to lay out guidelines for appropriately diagnosing someone with a mental health condition. Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common, annually affecting 19.1% and 10.4% of American adults respectively. For a patient suffering from anxiety, the DSM-V lays out symptoms and the level of daily impairment a patient must be experiencing to receive a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). These include the duration, breadth, and content of anxiety, as well as the presence of somatic symptoms, such as fatigue or restlessness, not explained by a different physiological cause. While the treatment varies across conditions, the overarching principle remains the same: the evidence we have supports a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. A patient diagnosed with GAD is likely to be prescribed a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) and is recommended for a therapy programme, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. Although this is considered standard treatment, the success rate of this regimen broadly varies. This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients with GAD may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways. While there are many components missing in this model, I will delve into three that I have found to be largely absent.

“This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways.”

Mental health diagnosis and treatment largely rely on using the individual as the focal point. As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold. In South Asian cultures, there is a high degree of interconnectedness between families and communities, spanning generations. Thus, the concept of ‘the individual’ is diluted. There is a protective element here; ideally, the burdens that one person may have to carry will be bolstered by a community. However, in a dysfunctional dynamic, the diminishment of the individual sphere turns into undue burdens forcibly carried by many. This ties in with the idea of intergenerational trauma. Young South Asian Americans today are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who lived to see the end of colonialism in India. Many are children of parents who immigrated to the West, facing poverty, racism, and uncertainty in a new country. These are not easy events for any generation to cope with, let alone within South Asian culture, where traumatic events are not openly spoken about. There is a profound alteration of sense of self that comes with traumatic occurrences, which can be greatly magnified when it occurs within a culture that also de-emphasises the individual. A communal notion of self can also make it difficult for a person to recognise intergenerational patterns that may be harming them. Contingently, a collectivist focus makes it difficult for many South Asians—whether they are from the era of Indian independence or they are influenced by modern-day societies—to buy into a mental healthcare system that places focus largely on the individual.

Image credit: Unsplash

“As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold.”

Language is another major barrier in providing nuanced mental healthcare. As clinicians, we use terms like “major depressive disorder” and “generalised anxiety disorder” to demystify. These labels make sense for those who work in healthcare, but what do they really mean to individuals who have never heard these terms before? What do they mean to those who do not speak English? The majority of the clinical language used to describe mental health come from a Western context and are amenable to English speakers. As seen by the portrayals in South Asian media, including cinema, a large number of South Asian languages do not use or have words that speak extensively or objectively about mental health. Thus, it becomes difficult for people to be aware of these issues, let alone act against the stigma around them, when there are barriers for communicating about them.

Finally, each community should be framed within the context of how they view the healthcare system. Like many immigrant communities, there is a degree of mistrust regarding healthcare amongst South Asians. Given the rich history of Eastern medicine within the region, there is an ongoing balance between how much trust the community will divvy up between these traditional, generational healing practices, and Western medicine. A 2016 study in BMC Endocrine Disorders looked at South Asian opinions on diabetes medicine and found a prevalent theme of scepticism. Many of those surveyed worried about drug toxicity, drug interactions, appropriateness of their therapies, and more. Doubt in the healthcare system, coupled with the underlying stigma and shame that South Asian communities hold towards mental health conditions, makes it all the more difficult to seek out help. As many South Asian languages do not have words to describe mental health conditions, negative terms end up being used in their place, increasing the shame around these conditions. According to a 2019 review, shame is deeply woven into the South Asian community and acts as a major barrier towards acceptance and treatment of mental health disorders. Stigma also creates a paradoxical problem: although South Asian cultures are largely collectivistic, the shame surrounding mental health is often so potent that any such problems become the individual’s fault. The effects of this can be devastating. Interconnectedness creates an erosion of the sense of self that is not particularly conducive to handling major stressors and mental health concerns.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health.”

Ultimately, these are only some of the barriers facing South Asian immigrant mental healthcare. There are countless other cultures and innumerable nuances that need to be understood in caring for their mental health. It would be impossible to expect public and clinic health providers to be well versed in the struggles of every community. The idea of culturally competent care—which refers to the ability of healthcare professionals to understand, respect, and interact with patients with cultures and value systems different from their own—recognises this. The core principle here is curiosity; healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health. Care must also be framed within the context of how the culture views Western healthcare as well as the stigmas it holds regarding not only Western medicine, but mental health overall. For an arena as complex as mental health, there are no clear-cut answers. Simply put, nuance is needed to fight our myopia when it comes to sensitive care in immigrant communities.

Gender inequalities and women's health in South Sudan

Aishwarya reveals the outcomes of a research study conducted in South Sudan, shedding light on the humanitarian response programme concerning COVID-19 and the floods, and their impact on women.

Content warning: this article mentions gender and sexual based violence

South Sudan is in a vulnerable position, as it has a low capacity to cope with the global COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic, in combination with existent poverty, high illiteracy rates, and an ineffective public healthcare system, has resulted in a battle in South Sudan for its people. Moreover, heavy rain, floods, waterlogging, and displacement have impacted rural communities in remote provinces in the Jonglei state. Floods have also caused shelter and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) challenges. These challenges are a key public health issue within international development, as they are part of the first two targets of Sustainable Development Goal 6 by the United Nations General Assembly in the year 2015.

While the world is battling with the deadly virus, people in South Sudan are grappling with floods and heavy rain. “We are more worried about lack of food than we are worried about COVID-19,” said a respondent from our project titled ‘Process Learning of Christian Aid’s DEC COVID-19 Appeal in South Sudan’. This article discusses our research, which sheds light on the humanitarian response programme to both COVID-19 and floods, and explores the response in the context of women’s needs specifically. The study aims to understand the role of local communities and marginalised groups in Christian Aid’s Integrated COVID-19 Response Programme. Additionally, it offers recommendations for long-term recovery actions. The research was conducted through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, along with household surveys in two provinces in Jonglei state, Fangak and Ayod.

Image credit: Unsplash

“While the world is battling with the deadly virus, people in South Sudan are grappling with floods and heavy rain.”

During these surveys, we were exposed to different risks that impact the lives of women in their communities, including patriarchal norms, lack of menstrual hygiene products, and the collapse of WASH facilities. These examples illustrate that the humanitarian response needs to take gender dynamics into consideration in order to implement equitable and effective programmes.

Gender

Food is crucial to communities, yet the process and responsibility to obtain it is dictated by patriarchal norms. Women in these communities, known as Neur, are imposed with the responsibility of bringing food to the plate under any circumstance. While the entire community is submerged under water due to floods and waterlogging, food accumulation becomes a tough task for everyone—not just women. Men expect women to look after “the food aspect” because according to them, they are usually “far away from home” to “earn money” or to let the cattle graze. Women tend to pick water lilies, weeds, and water grass from the swamps, and convert them into flour by drying and grounding, providing food for their families. They are also responsible for catching fish from the flood water, which are boiled or made into stews. Unlike men, who tend to have equipment for farming and cultivation, women have nothing of the sort and usually use what they have available, such as their bare hands and their clothes. According to female respondents, they use their frock or clothes to catch fish while squatting in the swamps.

The health outcomes observed from these practices include skin infections, vaginal infection, and skin rashes—attributable to the unhygienic flood waters in which they sit for prolonged hours to hunt food. In our household survey, 95% of the total respondents were female. While interviewing them, it was evident that there are gaps in community participation and gender inclusivity.

In a further workshop that we conducted, participants shared that women in this community have no rights over their own sexual reproductive health, as they could not decide who they marry, or when they get pregnant. There have also been instances where a man rapes a woman and she is forced to marry the perpetrator. Patriarchal attitudes along with the flooding has led to destructive impact on the sexual and reproductive health of females in these communities.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Patriarchal attitudes along with the flooding has led to destructive impact on the sexual and reproductive health of females in these communities.”

Menstrual Hygiene

Menstrual hygiene emerges as a growing need—the survey shows that 60.1% of the female respondents do not use any materials for maintaining menstrual hygiene, while 17.6% use old clothes or rags as a substitute for sanitary pads. During interviews with several women in the community, the participants mentioned that they “let it flow” or simply “avoid going near men”, as they either don’t have access to menstrual pads or have not been informed about menstrual hygiene products.

“We do not have sanitary towels, most women here don’t even know what that is,” said a female member during a focus group discussion. In the survey, 41.4% of respondents viewed “talks on menstrual hygiene” as something that should not be publicly discussed. However, 23.2% suggested that if menstrual hygiene awareness was provided to their spouses as well, it could help them to handle menstrual hygiene “culturally and respectfully” within their family circles.

In the context of these taboos about public displays of menstrual hygiene, 40.8% of respondents stated that when disposing of menstrual hygiene products they “hide them away” from men instead of disposing of them in a hygienic manner. 25.7% bury them, while 12.8% “wash them for re-use” and 1.9% throw them away in open spaces. As such, sanitary products are seen thrown away in the flood waters.

While diving deeper into the challenges faced by women in the community on a day to day basis, it’s evident that factors like floods, rains, and waterlogging can’t be the only reason for these problems. Lack of community participation programmes by both the government or humanitarian agencies, and the absence of counselling and awareness programmes all contribute to a lack of knowledge. Female respondents stated that the presence of these might be useful to better manage their menstrual hygiene needs.

Collapse of WASH

The floodings have changed the dynamics of hygiene practices. Several respondents claimed that people in the community drink the same (flood) water that they defecate and bath in. Every situation here is connected to one another: lack of toilets leads to open defecation and lack of dry land due to floods leads to defecation in the flood waters. According to our survey, only 6% had access to a latrine. However, existing toilet facilities do not work, so most people continue to defecate in the open, usually in flood waters.

Image credit: Unsplash

In the absence of clean water for drinking and domestic use, people had no option but to use the logged water in front of their houses. There are limited practices of boiling or filtering water, so in most cases they consume or use it directly. This contributed to several water-borne diseases among people along with skin infections and Urinary Tract Infection (UTIs). In case of UTIs, people manage by “praying to God” for protection as they either shy away from seeking help or simply lack medical assistance.

COVID-19