Cancer survival: due to patient or healthcare system characteristics?

Matthew argues that rapid cancer diagnostic pathways must be equally and proportionally accessible to all patients in order to close the deprivation gap in cancer survival rates.

Cancer survival is improving and has doubled in the last 40 years in the United Kingdom. However, the increase in survival has not been the same for everyone: it is leaving behind those who are more deprived.

Figure 1: Five-year relative survival (%) by deprivation category (detailed later) and calendar period of diagnosis in England and Wales. Relative survival, or net survival, is the survival probability derived solely from the cancer-specific hazard (risk) of dying and is independent of the general population mortality, i.e., competing risks of death.

Figure courtesy of Bernard Rachet, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

Until the early 2000s, less than half of people diagnosed with cancer were expected to live for five years. Since the introduction of the National Health Service’s (NHS) Cancer Plan in 2000, cancer survival has rapidly increased. The NHS Cancer Plan, and successive cancer policies, recognised the importance of an earlier diagnosis on the chances of a good prognosis. Thus, there was a greater drive to increase the proportion of patients diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Over the past two decades, the proportion of patients having their cancer detected earlier has dramatically increased, contributing to the rise in cancer survival. This trend is in large part due to factors such as awareness campaigns (e.g., association of smoking and risk of lung cancer), cancer screening initiatives (e.g., checking for lumps in breast cancers), and advancements in treatments and technology (e.g., positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans).

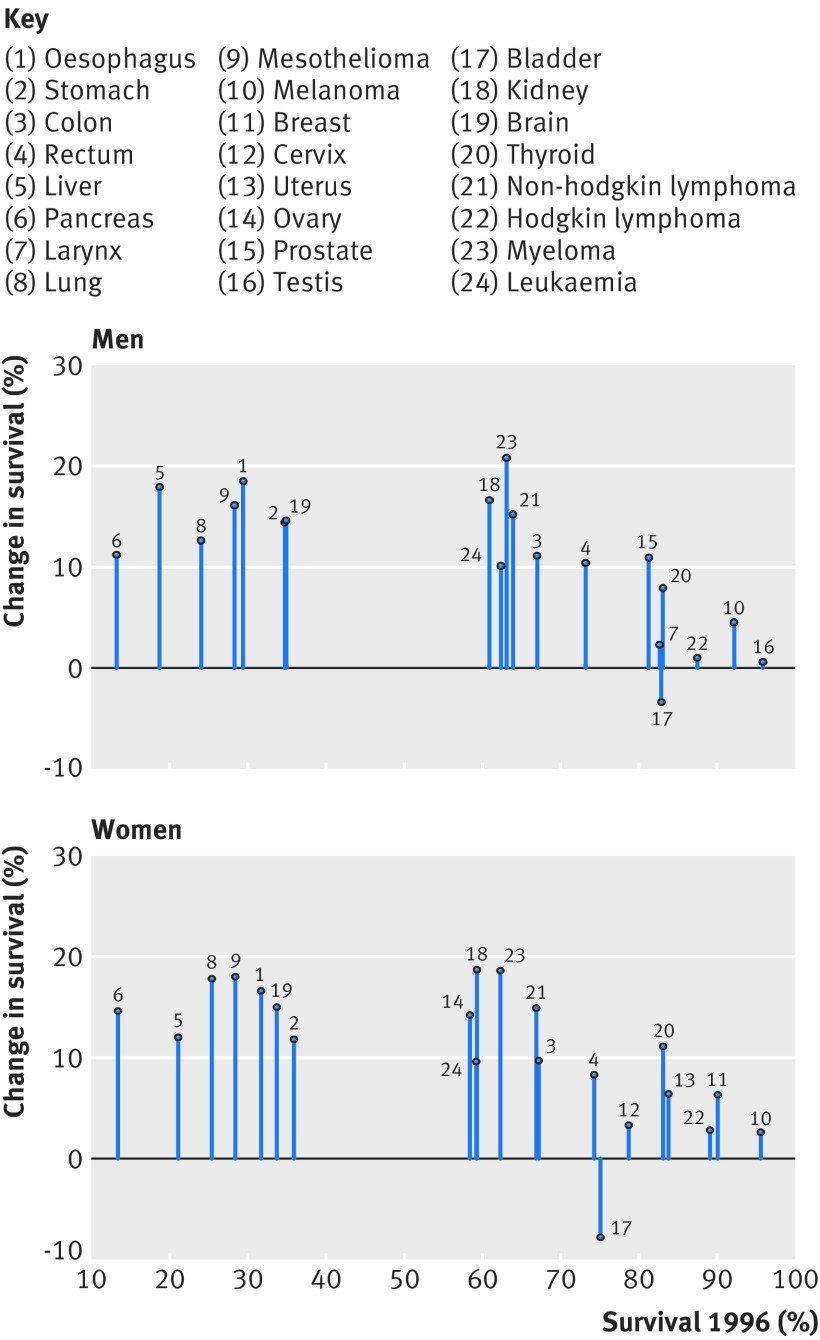

Figure 2: Change in one-year net survival between 1996 and 2013 for 20 cancers in men and 21 cancers in women. For example, amongst women, patients with pancreatic cancer had the lowest survival in 1996 but survival increased by approximately 15% by 2013.

Figure courtesy of Aimilia Exarchakou, Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes Network

In population-based cancer survival research, the measure of deprivation has evolved from a composition of Karl Marx’s structural and Max Weber’s societal perspectives. It is defined as the socially derived economic factors that influence what positions individuals or groups hold within the multi-faceted structure of society. Deprivation is a contextual measure of not only income but of one’s opportunities within their immediate area that are identified by several domains (employment, education, etc.). An individual’s assigned deprivation level is determined by the rank of their area relative to other areas in terms of a weighted combination of the domains. Thus, an individual’s level of deprivation is (i) an ecological measure and (ii) relative to other individuals. The latter is an important characteristic to consider since the areas with lower ranks are interpreted as more deprived areas compared to areas with higher ranks: they are not necessarily all deprived areas.

However, for some cancers, survival amongst those living in least deprived areas has improved faster than in more deprived areas. In other words, an unexpected but obvious phenomenon has occurred: there has been a marginal increase in survival, but the difference between deprivation groups has grown wider. Amongst males, the greatest widening was observed for melanoma, prostate, colorectal, and haematological malignancies; amongst females, it was gynecologic cancers. What is less obvious but no less important is that, apart from lung and brain cancers, the deprivation gap for any cancer has not narrowed. The bottom line is that these cancer plans have not targeted all patients equitably; they have missed patients who are living in more deprived areas.

Reasons for persistent inequalities

Unless the deprivation gap in survival is addressed, these inequalities are expected to persist or even widen in some cases. Cancer survival is often described by patient characteristics, such as sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic level. This has contributed to a common public misconception that patients with certain characteristics are predetermined to have lower chances of survival; however, patient characteristics account for approximately only a third of the socioeconomic inequalities. In fact, most of the socioeconomic inequalities in survival are due to unknown factors (other than patient characteristics). Optimal interactions between the patient and the healthcare system around the time of cancer diagnosis can drastically increase a patient’s chances of a better prognosis. Such optimal interactions include: effective communication during a general practitioner (GP) appointment, distinguishing between comorbid and cancer-related symptoms, being referred from a GP to a consultant within two weeks, and promptly receiving the diagnostic test and results. The problem is that these optimal interactions are less likely to be experienced by those in more deprived areas.

The current framework for cancer diagnoses is the rapid diagnostic and assessment pathway, such as the colorectal cancer diagnostic pathway (Figure 3). The aim of the diagnostic pathway is to ensure patients receive the outcome of diagnostic tests within 28 days of referral. Indeed, reducing the time that a patient is on the diagnostic pathway will contribute to an earlier diagnosis. However, to be fully effective it is crucial that the diagnostic pathway starts when the cancer is in its early stages—in reality, patients may have cancer months before they have the consultation with a GP that initiates the pathway. The diagnostic pathway could be thought of as a product of a company that is accessible to those who can “afford” it in a society where the currency is “privilege of accessible healthcare services”. It is not the function of the diagnostic pathway that is systematically biased, it is inaccessibility that induces bias.

The diagnostic pathway is susceptible to two major flaws resulting from access: GP availability and testing capacity. Firstly, the number of GPs within any area must be proportional to the size and healthcare requirements of the population they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with less GPs may have a reduced chance of accessing the diagnostic pathway. Secondly, the number of specialists and the capacity of diagnostic facilities that feature along the pathway must be proportional to the demand of any area they care for. Without this proportionality, those living in areas with unavailable diagnostic specialists or facilities will have a reduced chance of receiving a definitive diagnostic result (including earlier diagnosis) within 28 days of a GP referral.

Figure 3: Colorectal cancer rapid diagnostic pathway. (MDT: multidisciplinary team, GP: general practitioner, CT: computed tomography, OGD: gastroscopy, CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen test, CNS: clinical nurse specialist, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, TRUS: transrectal ultrasound.)

Figure courtesy of NHS Cancer Programme (NHS England)

To elaborate on the first flaw (GP availability), the number of GPs is not only lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, but there is an exodus of GPs across England, leading to a comparatively higher workload for GPs who do work in these areas. Moreover, GP time for each patient is, on average, lower in more deprived areas compared to least deprived areas, even for patients with comorbidities. This is an example of the inverse care law: those who most need care are the least likely to receive it. Higher workload for GPs, in combination with reduced GP time, increases the chances of missing ‘red flags’ of cancer symptoms. Furthermore, more deprived areas tend to be more densely populated and have a higher prevalence of patients with comorbidities. More densely populated areas are likely to have a healthcare service with a higher demand, leading to an increased chance of patients being diagnosed through emergency route, which is closely correlated to a later cancer stage at diagnosis. A natural, and foreseeable, consequence is a future with a reduced number of cancer patients from deprived areas on the diagnostic pathway, ultimately leading to the sustained deprivation gap in cancer survival.

Figure 4: Number of registered patients per GP by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in order of deprivation level.

Figure courtesy of The Health Foundation

To elaborate on the second major flaw (testing capacity), a key phase of the cancer diagnostic pathway is during Days 3 and 14 (the Straight to Test [STT] phase), when the cancer-specific test is expected to occur. One commonly required procedure is a computed tomography (CT) scan, which is carried out by a radiologist. The same issues around accessibility materialise again: not only is there a radiologist shortfall, but millions are spent on scan outsourcing. Some of the key findings of the Royal College of Radiologists’ (RCR) annual census (2020) were that the UK radiologist workforce is now 33% short-staffed, with a projected rise to 44% by 2025. Additionally, consultant attrition remained at an average of 4% within the UK. Previous data from the RCR highlighted that scan outsourcing in 2017 rose by 32% since 2016. The cost of scan outsourcing (paying private companies to help with the workload) was estimated to be £116m in 2017 (enough to pay 1,300 full-time radiologists). With no clear influx of radiologists, and an increasing demand for CT scan usage over the next few years, the deprivation gap in cancer survival is unlikely to narrow.

Reducing inequalities

There are multiple factors contributing to socioeconomic inequalities. However, increasing the NHS budget to improve the ratio of patients to GPs and radiologists would drastically reduce the deprivation gap in cancer survival. The healthcare system can only go so far as to be more efficient with the same budget; each year, there is a higher demand for additional services that heavily outweighs the annual increase of the NHS budget. Even advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis, comes with its own inherent inductive bias that may itself contribute to the deprivation gap in survival. Without the appropriate capacity for demand in the areas where care is most needed, it is unlikely that we will see a reduction of the socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival and the true potential of faster cancer diagnostic pathways.

The heroes we are not

Oluwaseun uses poetry to describe the frustrations and exhaustion that comes with being a frontline healthcare worker despite their bravery and commitment being celebrated by others.

Oluwaseun was inspired to write this piece after experiencing what it was like to work on the frontline with a tired team. She explores how when her colleagues and herself want to discuss issues that they face us as a staff group, people often make remarks that denies them a place to express their feelings in a safe space. This poem explores that frustration and the toll that it can take on already tired healthcare professionals, who really love what they do, but still want to be seen as people.

Image credit: Unsplash

Today, like any other day, I put my uniform on and wear the badge of hero, national treasure

The burden, the burden.

Has anyone stopped to look at the woman who wears the badge?

“I can’t be the only one”

I know I am not.

This hero, as human as she is, as every one of us is, chose to rise today

She chose to rise, work, and give.

I’m a little tired, but so is the woman who has been here for 8 hours with no answers in a room full of people she doesn’t know

“Am I carrying too much? Can I do more?

I wish I could I wish we could.”

We are all in this together; the comradery is incredible

I still smile and get excited at the thought of another day growing and serving

I still think it is a privilege

But my reserves are hollow barrels now

“We are very busy at the moment. I’m sorry it has taken so long for us to get to you”

I’ve said that too many times.

The woman, the man, the child, the being

They bring their fears here

Asking us to hold onto them with dignity and honour

I see them and carry them

But the problem is

I am human too

We all are

“We need to get this right and do better, we can’t have this for the patients”

That’s true,

You’re right but has anyone stopped to look at me? At all of us?

The people in the uniforms

We come with our perfectly flawed conceptions, personality traits, and tendencies

We come with our problems, our ideas, our brilliance

Our conflicts

We come with the wholeness of who we are

These things are what we serve with

Does anyone see that?

Image credit: Unsplash

We come with mistakes and through our reflections we rise up from them together

Is there any grace for that?

Is there any grace for the people who, with courage and limited resources, give?

Is this house still holding us?

When we pour out the maps of our minds and the burdens of our hearts will you still call us heroes?

Is there space for a garden to bloom?

I am like any other woman who chooses to rise and stand

Whether she is in a classroom, a home, an office or a business

I am not a hero; I don’t think I ever will be

If heroes are silenced when they protest and speak then I never hope to be that.

What I am is human

And, I will be that till the day I die.

And, what I put on is courage

I have seen the depths of what it means to be human in my uniform

In anger, in confusion, in sadness, in trauma

I have seen the rawness of it, its poignance

For that I will not be a hero

I will be a human, learning day by day, as I choose to wear my uniform.

Improving nuance in South Asian immigrant mental healthcare

Pallavi discusses the ways in which Western approaches to mental healthcare fail to recognise the nuances of immigrant communities, cultures, and conceptions of self.

If there is anything the pandemic has shown us, it is that isolation is exceptionally rattling. A June 2020 survey by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 40.19% of adults were experiencing depression, anxiety, PTSD, or substance abuse in the United States. This was three to four times higher than the rates reported just the year prior. Thus, the need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations. Yet, the diagnosis and treatments we assign to these mental health conditions often do not recognise nor appropriately address these differences. While there is some degree of universality in the human experience, there must be greater nuance and understanding in how we provide mental healthcare, especially in vulnerable and underserved populations. To illustrate this need, I will specifically be looking at how mental health is diagnosed and treated in the United States (US) and how this approach often does not work for the South Asian population here.

Image credit: Unsplash

“The need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations.”

The medical system in the US is ascribed by the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V). The DSM-V is a collaborative work created by mental health professionals to lay out guidelines for appropriately diagnosing someone with a mental health condition. Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common, annually affecting 19.1% and 10.4% of American adults respectively. For a patient suffering from anxiety, the DSM-V lays out symptoms and the level of daily impairment a patient must be experiencing to receive a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). These include the duration, breadth, and content of anxiety, as well as the presence of somatic symptoms, such as fatigue or restlessness, not explained by a different physiological cause. While the treatment varies across conditions, the overarching principle remains the same: the evidence we have supports a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. A patient diagnosed with GAD is likely to be prescribed a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) and is recommended for a therapy programme, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. Although this is considered standard treatment, the success rate of this regimen broadly varies. This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients with GAD may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways. While there are many components missing in this model, I will delve into three that I have found to be largely absent.

“This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways.”

Mental health diagnosis and treatment largely rely on using the individual as the focal point. As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold. In South Asian cultures, there is a high degree of interconnectedness between families and communities, spanning generations. Thus, the concept of ‘the individual’ is diluted. There is a protective element here; ideally, the burdens that one person may have to carry will be bolstered by a community. However, in a dysfunctional dynamic, the diminishment of the individual sphere turns into undue burdens forcibly carried by many. This ties in with the idea of intergenerational trauma. Young South Asian Americans today are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who lived to see the end of colonialism in India. Many are children of parents who immigrated to the West, facing poverty, racism, and uncertainty in a new country. These are not easy events for any generation to cope with, let alone within South Asian culture, where traumatic events are not openly spoken about. There is a profound alteration of sense of self that comes with traumatic occurrences, which can be greatly magnified when it occurs within a culture that also de-emphasises the individual. A communal notion of self can also make it difficult for a person to recognise intergenerational patterns that may be harming them. Contingently, a collectivist focus makes it difficult for many South Asians—whether they are from the era of Indian independence or they are influenced by modern-day societies—to buy into a mental healthcare system that places focus largely on the individual.

Image credit: Unsplash

“As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold.”

Language is another major barrier in providing nuanced mental healthcare. As clinicians, we use terms like “major depressive disorder” and “generalised anxiety disorder” to demystify. These labels make sense for those who work in healthcare, but what do they really mean to individuals who have never heard these terms before? What do they mean to those who do not speak English? The majority of the clinical language used to describe mental health come from a Western context and are amenable to English speakers. As seen by the portrayals in South Asian media, including cinema, a large number of South Asian languages do not use or have words that speak extensively or objectively about mental health. Thus, it becomes difficult for people to be aware of these issues, let alone act against the stigma around them, when there are barriers for communicating about them.

Finally, each community should be framed within the context of how they view the healthcare system. Like many immigrant communities, there is a degree of mistrust regarding healthcare amongst South Asians. Given the rich history of Eastern medicine within the region, there is an ongoing balance between how much trust the community will divvy up between these traditional, generational healing practices, and Western medicine. A 2016 study in BMC Endocrine Disorders looked at South Asian opinions on diabetes medicine and found a prevalent theme of scepticism. Many of those surveyed worried about drug toxicity, drug interactions, appropriateness of their therapies, and more. Doubt in the healthcare system, coupled with the underlying stigma and shame that South Asian communities hold towards mental health conditions, makes it all the more difficult to seek out help. As many South Asian languages do not have words to describe mental health conditions, negative terms end up being used in their place, increasing the shame around these conditions. According to a 2019 review, shame is deeply woven into the South Asian community and acts as a major barrier towards acceptance and treatment of mental health disorders. Stigma also creates a paradoxical problem: although South Asian cultures are largely collectivistic, the shame surrounding mental health is often so potent that any such problems become the individual’s fault. The effects of this can be devastating. Interconnectedness creates an erosion of the sense of self that is not particularly conducive to handling major stressors and mental health concerns.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health.”

Ultimately, these are only some of the barriers facing South Asian immigrant mental healthcare. There are countless other cultures and innumerable nuances that need to be understood in caring for their mental health. It would be impossible to expect public and clinic health providers to be well versed in the struggles of every community. The idea of culturally competent care—which refers to the ability of healthcare professionals to understand, respect, and interact with patients with cultures and value systems different from their own—recognises this. The core principle here is curiosity; healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health. Care must also be framed within the context of how the culture views Western healthcare as well as the stigmas it holds regarding not only Western medicine, but mental health overall. For an arena as complex as mental health, there are no clear-cut answers. Simply put, nuance is needed to fight our myopia when it comes to sensitive care in immigrant communities.

How the "menopause is natural” narrative is a damaging one

Aishwarya explains that discussing menopause as a natural phenomenon perpetuates social and health inequities, leaving women to push through their symptoms alone without practical and effective health advice.

If you Google menopause, a long list of symptoms appears. There may be a mention of how menopause symptoms are unique from person to person and advice not to take the list of symptoms at face value. But that part may be skipped over, leading straight into a paragraph on hysterectomies and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). This paints menopause as a well-structured process with simple solutions. It was only when I began to search for research papers on menopause in India that I uncovered a glaring problem: in conversations about menopause, authentic experiences had been left out completely.

Image credit: A. Krivitskiy via Unsplash

“In conversations about menopause, authentic experiences had been left out completely.”

Menopause is the one-year anniversary of a person’s last period. Since a person is born with a finite number of eggs in their ovaries, at a certain age, usually between 35 and 55, the number of eggs reaches below a threshold. Oestrogen—the hormone responsible for retaining and maintaining this constant—begins to fluctuate from its cyclical nature. As oestrogen governs more functions than just the menstrual cycle, decreasing hormone levels also result in a spectrum of symptoms throughout the body. For example, oestrogen plays a key role in controlling body temperature, and a low oestrogen level can cause a sudden spike in body temperature known as a ‘hot flash’ or ‘hot flush’—a common symptom of menopause.

I decided to conduct my postgraduate research on menopause experiences of cis-women in India through qualitative interviews. My research asked: if women were reporting difficulty during their perimenopause (the 5–15 years of physiological changes leading up to menopause), were their negative experiences a result of not making use of the available medical facilities? Since COVID-19 had limited my sample to middle-class women with access to Zoom, my participants were all literate and had easy access to hospitals and gynaecologists. But by the end of the first interview, it was clear that I had a lot to learn. My ignorance stemmed from a combination of my own privilege, and my education: studying science had distanced me from social issues and structures. By the end of my 30th interview, I had uncovered just how entwined social and health inequities are.

One of the most common phrases I heard was “it’s natural”. While menopause is indeed a natural phenomenon—after all, periods do eventually stop—calling menopause ‘natural’ seems to be doing more harm than good. If women are not accessing health infrastructure, and if health infrastructure is barely covering (or over-medicalising) the menopause, a deep dive into the ‘natural’ narrative may uncover some truths about where these health gaps lie. In the words of the women themselves, here is why the concept of menopause as ‘natural’ is both born from social inequities, and why using it perpetuates health inequities.

Calling it natural is a coping mechanism caused by lack of support

“Natural actually sounds good but I wish it was not traumatic. Not painful. I wish it was like, once you decide you don’t want to have kids you switch it off and everything stops. That would be more natural for me.”

Image credit: Unsplash

A menopausal support system requires two systems, each depending on the other to be effective: the social system and the medical system. While good gynaecologists may be available, most menopause symptoms do not have quick fixes. Dr Shaibya Saldanha, a gynaecologist in Bangalore, India, stressed the fact that menopause does not need to be a medical phenomenon. At the same time, she made clear that a natural process does not mean one without dietary and lifestyle interventions. For example, during perimenopause, sleep should increase while the body adapts to hormonal changes. However, “Women normally run on six hours of sleep … .They close the house down in the kitchen and feed every single person who eats at different times. And then they go to sleep and normally they would get up at 5:30–6:00 and start the next day.”

Solutions may appear feasible—such as sleeping for longer or shifting household duties to another family member—but support is often lacking. In a culture where gender roles are so deeply ingrained, social inequities play a role in menopause experiences. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic added to the workload of urban women, and this stress alone could have increased hot flashes and emotional fluctuations. Further, stigma surrounding menstruation continues into menopause. In some interviews, the women were unable to explain their menopause symptoms to their husbands because they had been discouraged from talking about their reproductive health during puberty.

This combination of shame and the lack of support at home leads women to use the word “natural” as a way of sweeping their health under the rug. If their health is not taken seriously then it must be unimportant, and most bodily processes that aren’t given attention are natural ones. Thus, menopause and its accompanying symptoms, no matter how harrowing, must be natural too.

An ayurvedic doctor that I spoke to explained how she bridged this gap. When a menopausal woman enters her clinic, this doctor ensures that either the husband or another family member is present during the consultation.

“Everyone takes doctors seriously and our word weighs. That extra step in counselling makes a big difference in fighting stigma.”

Image credit: Unsplash

Natural processes are common, and therefore you will manage

“Once [women] speak to their family they are ridiculed. Women of our generation are convinced, and it is very unfortunate, by women themselves. By women of the previous generation. They themselves say, ‘Oh you take this all so seriously, it’s very natural. You make a big deal out of nothing.’ Mind you this is not said by men. This is said by previous generation women. They are the ones who find it ridiculous.”

Two generations ago, treatment for menopause did not exist, nor did women have access to healthcare facilities. Tasked with running a household, women put their own health last. Along with the stigma surrounding menstruation, women had no choice but to manage their menopause alone. One of the most important long-term effects of the change in oestrogen level is a decrease of calcium uptake in the body. People going through menopause are encouraged to increase or supplement their dietary calcium intake so that postmenopausal concerns such as osteoporosis and arthritis are prevented. Unfortunately, rather than appreciating the availability of medical advancements for their daughters, women often look down upon other women who seek medical assistance. Silently suffering is seen as a display of strength: “We never used to complain about our cramps,” becomes “We never went to hospitals”. The prevalence of osteoporosis and arthritis in this generation shows just how damaging social inequities can be for health outcomes.

Image credit: Unsplash

Women’s health doesn’t warrant relevant medical attention

“We have a doctor but we don’t go much to the gynaecologist because it [menopause] is a natural process.”

Both postmenopausal women whom I spoke with regretted not having a check-up at the gynaecologist’s office. Yes, menopause is not a disease and nor is it a disorder, but, at the very least, a blood test to ensure that calcium and vitamin levels are normal is a must.

But the narrative around women’s reproductive health has always been ‘to manage’. Menstrual cramps in the middle of a class? Keep your head down and power through. A miscarriage? You’re shooed out the hospital door and expected to deal with the trauma on your own. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome? Despite it becoming an increasingly common condition, there is little progress in medical care provision. You’re handed a set of birth control pills and told to manage the side effects. Similarly, self-managing your menopause transition is the expectation. In fact, a woman who did seek medical help was dismissed by her gynaecologist who said, "Menopause is a part of life that everyone manages through.”

When it comes to menopause, unless your symptoms can be treated by medical intervention, there’s no space for a person going through menopause to seek guidance or support. “You have to stop everyone from removing your uterus,” was a common sentiment heard during my interviews with women. Instead of broadening the kind of support a medical environment can offer, menopause is medicalised and the fear of having unnecessary tests or operations prevent women from going to hospitals. Dr Saldanha told me frankly that there are only a few gynaecologists that sit menopausal women down and explain the practical lifestyle changes they can make to ease their symptoms. She had completed a one-year counselling course specifically so that she was better equipped to help the menopausal women who walked into her clinic. However, this kind of menopause counselling does not commonly feature in medical school curriculums.

Image credit: Unsplash

The lack of menopause education in medical schools because it is a natural process

“And I think that’s the nuances of medicine that is not taught to any of us as doctors. Beyond health; the needs of people. What about preventive health, what about a step beyond that?”

Menopause counselling sounds like a tall order, considering how menopause itself is barely covered in the MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery). Five women interviewed were medical professionals and they were all disappointed by the lack of menopause training. Public health tends to focus on the prevention of disorders, diseases, and ailments. Although menopause should not be looked at through any single lens, public health education and health promotion should encompass menopause. When discussed, menopause is also primarily and problematically grouped under ageing concerns. The average age of menopause in my study was 47, and women reported feeling disconnected with the concept of menopause being a sign of old age. Generations ago, menopause may have come towards the end of life, but lifespans are longer than they have ever been.

Image credit: Unsplash

“I don’t want to have one foot in the grave. I am working, I actually started a new academic program just this month. I don’t think of myself [as at] that age… It doesn’t have to be a natural part of the end in life. It’s going on while life is also going on.”

Rather than finding an answer to where and how menopause should be taught, it’s skipped over altogether, with medical colleges teaching a slide or two at most. This has led to many medical professionals not knowing what menopause symptoms are at all. Since the onset of perimenopause is unpredictable, women often visit a general practitioner first for their menopause symptoms. Unfortunately, many women in my study consulted multiple doctors before the word ‘menopause’ was even brought up.

How do we remove these systemic health and social inequities?

One of the most important things that I learned through these conversations is that ‘natural’ does not necessarily mean a ‘good’ thing. Although the menstrual cycle is a natural process, its stigmatisation turns it into something negative. On the other hand, the perception that everything “God-given” or “natural” has to be good prevents women from seeking help when a natural process doesn’t feel good.

Public health systems need to take the initiative to spread menopause awareness, and doing so should involve those who will not experience menopause too: de-stigmatisation begins with open conversations. It is thus imperative for menopause counselling to be a part of every gynaecologist’s training. Considering that menopause can intensify mood swings and lead to depression, “removing the uterus” should not be the only intervention that gynaecologists are equipped to provide. Validation is an important and missing component. All of the women who had negative menopause experiences thanked me for simply giving them a space to share what they had endured. Because of health inequities, doctors did not give them a safe space or the time of day to allow them to share their trauma; and because of social inequities, they were unable to openly discuss the negative aspects of menopause at home. A combination of more research and counselling would help to validate that what is natural is not always good. More often than not, women understand that they will have to push through their symptoms; they also want proof that what they’re going through is indeed natural, and that it is okay to not enjoy it.

Image credit: Unsplash

Menopause is something that cannot and should not be generalised for all. If the person makes the choice to seek medical support, infrastructure and solutions should be available. If the person decides to go through the menopause symptoms without any medical intervention, social systems should be available to support them. Most importantly, strengthening both social and health structures will allow people going through menopause to be able to rely on both. With neither system currently making space for menopause, the word ‘natural’ has become synonymous with ‘isolated’. Women deserve more.

“Menopause is something that cannot and should not be generalised for all.”

Why don’t our doctors look like us?

Dhruv illustrates why doctors often do not reflect the populations they serve through the stories of two medical students.

“Privilege is when you think something is not a problem because it is not a problem to you personally”

I’ve spent the past five years mentoring and guiding students who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) through medical school admissions in the United States (US). With their permission, I will share two stories to highlight some of the systemic causes for why doctors often do not reflect the populations they serve.

Andre identifies as African American and was born and raised in northern California. Although he faced many challenges growing up, he persevered and graduated from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Andre’s educational background was astounding: not only had he graduated from UCSD with a 3.95 grade point average, but along the way he had published four papers in the field of molecular biology and was working as a medical scribe in a primary care clinic in Sacramento. However, when Andre sat for the US Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), he scored in the 48th percentile—a score completely incongruent with his intelligence. After learning more about how he had prepared for the exam, it became quite clear why he scored lower than he was capable of. Andre was whip-smart and great at taking exams, but he didn’t know which resources to utilise and how to effectively prepare for a standardised test. No one had told him which question banks to buy, what books were the best, or how to develop a long-term study plan. The MCAT isn’t just any college exam; it often requires strategic knowledge and information privy to those with rich networks and resources. Once Andre had that information, he scored in the 97th percentile and is now a medical student in California pursuing primary care. Andre’s story shows how standardised tests are about more than a student’s intrinsic ability and will to achieve; they reflect the privilege and inaccessibility of higher education. There are also the temporal and monetary costs of taking the exam. Taking the MCAT once costs about $300 and students study for 30–40 hours per week for about three months. Both present additional obstacles for an exam that is touted as an equaliser in the field of medicine.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Standardised tests are about more than a student’s intrinsic ability and will to achieve; they reflect the privilege and inaccessibility of higher education.”

Tiffany lives in San Francisco and attended school on the East Coast of the United States. She aspired to go to medical school so she could be a physician in the community she grew up in. She speaks Vietnamese and understands the culture and background of her neighborhood. Previously, Tiffany was a stellar student and earned excellent grades and test scores, but her obstacles lay beyond her report card. Her extracurricular list was much shorter than her colleagues. Coming from a lower income household, she worked two jobs during her undergraduate to make ends meet. This meant she couldn’t pursue the same opportunities in research, community service, and unpaid clinical work as her classmates. I could feel her concern, worry, and lack of confidence. Despite her hard work, Tiffany did not see herself as an equal and valuable participant in the application process. She felt behind her classmates, and imposter syndrome settled into her psyche. Tiffany recently scored in the 90th percentile on her MCAT, and is now working as a medical technician at an ophthalmology clinic with plans to apply to medical school next year. Situations like Tiffany’s are sadly common, where bright students who would excel in medicine simply don’t have the money, either from their own pockets or from their family, to finance a diverse and impressive list of extracurricular activities. These students have no choice but to take a gap year (or more) to slowly build up an extracurricular list that can compete in the admissions battleground. Many students become consumed by these gap years and lose interest in a career in medicine. A truly equitable system should create opportunities for students, regardless of their financial situation.

Today, medical education includes a renewed focus on understanding and accommodating our patients’ backgrounds, and there has been much research into the benefits of a diverse physician workforce. These studies largely revolve around the idea that concordance between physicians and patients promotes greater understanding of the socioeconomic and cultural determinants that play a role during a given patient’s healthcare. To achieve such goals, the medical education system must create pathways to success for students who will represent and contribute to a diverse physician workforce so that one day our doctors look like our patients.

“The medical education system must create pathways to success for students who will represent and contribute to a diverse physician workforce.”