Trauma construction and traumatic events

In the first part of their essay series on cultural psychology, Kate and Mohammad draw attention to Dr Derek Summerfield’s critique of Western trauma narratives and reveal the limitations in our approaches to global mental health.

The era of white saviourism

Content warning: This article contains mentions of mental illness and racism.

In his groundbreaking work on decolonising trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in Palestinian territories, Dr Derek Summerfield calls for the reform of the treatment and overmedicalisation of mental health, particularly in humanitarian circumstances. The following two-part essay series understands trauma, in line with Summerfield's arguments, to be a condition manufactured by Western psychiatry, whereby the complex, unique, and often collective suffering of individuals is reframed as a technical problem to which short-term, individually-delivered solutions are applicable. In the second essay, the implications of Western framings of post-traumatic stress disorder will be explored further through the actions of non-governmental organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières. The series concludes by suggesting ways in which decolonising psychological care can improve inequalities in access to and treatment of mental health globally, as well as raise awareness surrounding the complexity of human nature and psyche.

Image credit: Unsplash

Western social constructions of trauma and traumatic events

“despite the fact that the diagnosis of PTSD was built from the specific experiences of male American veterans, its entry into the DSM-III meant that it became the definition applied to all, irrespective of culture, experience, background, ethnicity, or gender.”

Definitions of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first appeared in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). PTSD is described as “a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event” and is diagnosed through a series of DSM criteria, including “intrusion symptoms” like nightmares or flashbacks, and “negative alterations” in mood or reactivity like feelings of isolation and anger. The DSM-III and its subsequent versions (the DSM-5 being the most recent edition) are American-made manuals that have become used globally, supposedly offering a guide to psychiatry written in a “universal language for clinicians”. However, understandings of trauma were first premised on the early experiences of American soldiers returning from the Vietnam war in 1975. In part, the trauma experienced by these soldiers was given the label PTSD as a means to depict these soldiers as solely victims of the United States’ military establishment as opposed to individuals who had also perpetrated atrocities. In this case, the PTSD diagnosis legitimised the suffering of Vietnam veterans, and offered short-term relief to their distressing symptoms. Yet, despite the fact that the diagnosis of PTSD was built from the specific experiences of male American veterans, its entry into the DSM-III meant that it became the definition applied to all, irrespective of culture, experience, background, ethnicity, or gender.

The diagnosis of PTSD has spread to all countries subject to Western imperialism. The transition of PTSD from its localised socio-political origins into ‘objective biomedicine’ demonstrates the power of colonial channels and Western ideologies. Temporally specific diagnoses of trauma that emerged during America’s war on Vietnam have been erroneously regarded as universal and context independent, and thus applied worldwide. Suman Fernando—a lead scholar in the correlation between mental health treatment and racism—describes this as an imperialistic process: Western powers “marginalise other ways of knowing, destroy diversity, make alternatives to psychiatry vanish and create monocultures of the mind”.

“Temporally specific diagnoses of trauma that emerged during America’s war on Vietnam have been erroneously regarded as universal and context independent, and thus applied worldwide.”

How do Western conceptions of trauma engender inequality in mental health treatment?

In areas of conflict, Western non-governmental organisations distribute and deploy trained medical staff to deal with the fallout of violence and to treat early trauma signs. However, the deployment of medical staff trained in Western-centred psychiatric medicine in non-Western contexts is self-defeating. The challenge for Western medical staff is attempting to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to mental healthcare in individuals with symptoms unexplained or not understood by Western training. In taking such an approach, ownership of what is deemed important in traumatic events is transferred from those experiencing it to Western bodies deemed to know better, those “whose knowledge carries a stamp of authority”. The understanding of Western psychiatry as a globally-applicable science implies that the vast experiences of trauma survivors can be easily reduced into a single mental illness classification of “PTSD”. Thinking of trauma in this regard is simplistic, and invalidates the experiences of trauma survivors.

“ownership of what is deemed important in traumatic events is transferred from those experiencing it to Western bodies deemed to know better”

For example, on the premise of a PTSD diagnosis, many patients receive Western treatments such as counselling or medication, which “offer little in the way of alleviating the underlying causes of collective trauma”. Collective trauma refers to the “psychological reactions to a traumatic event that affects an entire society”. Acknowledgement of collective trauma is vital to validating the stories and emotions of survivors both before and during the traumatic events. By accounting for broader frameworks of “social justice, quality of life, human rights and human security”, a more nuanced understanding of the survivors' responses within the collective memory and experiences of their society can be gained, and adequate treatment provided.

“Western narratives arguably regard sufferers of collective trauma and psychological ill-health as passive bodies in need of treatment, as opposed to survivors with valid experiences.”

Furthermore, emotional distress experienced by survivors is generally hard to empirically measure in the categoric style of Western psychiatry—a limitation further exacerbated by a lack of cultural understanding. Deployed medics’ lack of knowledge or willingness to understand local idioms of distress leads to misdiagnosis and misinterpretation, pathologising of symptoms, and prescribing medication that is in some cases unnecessary and of little effect. Western narratives arguably regard sufferers of collective trauma and psychological ill-health as passive bodies in need of treatment, as opposed to survivors with valid experiences. This narrow understanding shapes and often rewrites the ways in which people view themselves as victims, which can worsen or complicate existing experiences of psychological ill health.

The dominance of Westernised trauma narratives is contingent upon the funding of Western psychiatric research and the value attributed to the Westernised methods, with very little insight into varied cultural understandings of trauma and the local idioms in which they arise. Studies that are academically and financially valued are those which underpin Western institutions’ own understanding of trauma narratives, thereby deepening Western-centric knowledge systems, while simultaneously excluding the experiences, symptoms, and accounts of trauma globally—a symptom of the colonial legacy in scientific research. With many international organisations prioritising Western-centric understandings of psychology, along with research funding being allocated to institutes mainly in the West, culturally sensitive research is excluded from international policies.

“Studies that are academically and financially valued are those which underpin Western institutions’ own understanding of trauma narratives, thereby deepening Western-centric knowledge systems, while simultaneously excluding the experiences, symptoms, and accounts of trauma globally”

For example, in tracing the history of Palestinian mental health diagnosis and treatment, Giacaman et al. emphasise the importance of “separating clinical responses to mental illness from the public health response to mass political violation”. It must be recognised that war and violence is a collective experience. Summerfield states that when witnessing the destruction of their social world, survivors lose embodiments “of their history, identity and living values and roles”. Therefore, to exclude such experiences, and to exclude context-specific socio-political understandings of trauma, can only cause further harm to survivors. The authors emphasise the need for a shift from the individual focus of Western medical indicators to broader global factors in trauma, such as a lack of human security and human rights violations.

In sum, the trend of excluding cultural contexts of trauma sustains global hierarchies. The West and “the rest” mentality reinforces centuries-old colonial structures and channels of power that depend upon stereotypes and generalisations. Such power imbalances result in an inability to reconcile different cultures, widens racial inequalities, and limits access to proper mental healthcare in resource-poor settings.

Western conceptions of trauma

In the second part of their essay series on cultural psychology, Kate and Mohammad take a closer look at the origins of international aid group Médecins Sans Frontières and discuss future directions for the continuing decolonisation of global mental health.

The case of Médecins Sans Frontières

Content warning: This article contains mentions of mental illness, racism, and discriminatory language.

Trauma projects and expeditions to ‘aid’ victims in resource-poor settings have become increasingly attractive and are fashionable for Western donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). However, the permeation of Western schools of thought surrounding trauma limits the degree to which the actions of these non-governmental organisations are effective or helpful. For example, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) deploys hundreds of their staff to conflict situations or areas affected by natural disasters. They have saved the lives of people worldwide, providing medical aid to all regardless of differences in their race, religion, creed, or political affiliation. Whilst MSF and their staff (from Western and non-Western countries) have shown courage and selflessness in their attempts to care for those most vulnerable around the world, their acts of goodwill do not come without criticism. This second part of this essay series will explore the extent to which NGOs are manipulating situations in areas of conflict and natural disaster by constructing trauma narratives as ‘epidemics’ in urgent need of attention to gain further donations, publicity, and resources. Lastly, we will explore the damaging consequences of being depicted as receptive patients or helpless victims by aid missions.

Image credit: Unsplash

Founded in France in the second half of the twentieth century, MSF is a private international association of doctors and healthcare professionals working to “provide assistance to populations in distress”. Despite their pledge to observe “neutrality and impartiality”, their humanitarian aim is deeply rooted in Western ideals of human rights. The rigidity of these ideals mean issues are framed and solutions are generated through the lens of colonial thinking. In the simplest sense: a humanitarian mission originating from a European country to help people deemed to be in need in Africa or Asia resembles colonial civilising missions. More specifically, in the case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), repetitive quotes in the media referring to trauma as the “hidden epidemic” likens the psychological condition to concrete communicable diseases capable of causing mass pathology. Framing localised trauma as Westernised conceptions of PTSD provides an incentive and authority for companies such as MSF to “resolve the issue”.

For example, the MSF handbook on refugee health makes claims that “20% of survivors of traumatic experiences will not recover without professional help.” Such language works to posit MSF as saviours and superior bearers of knowledge and healing, linguistically reflecting a “modern echo of the age of Empire when Christian missionaries set sail to cool the savagery of primitive peoples and gather their souls, which would otherwise be lost”. The colonial use of language was exemplified in the wake of the Rwandan genocide, when European NGOs sought out to make an early psychological intervention for the Tutsi refugees as a “preventative measure to thwart the later development of more serious mental problems,” inciting a sense of fear towards trauma and a need to “control the mentally ill of the global south”. However, the NGOs failed to provide adequate treatments, as concepts integral to the English understanding of trauma such as ‘stress’ and ‘family member’ were not translatable in Kinyarwanda and didn’t apply to Rwandan social contexts. As such, Western knowledge and its tools are incapable of identifying the expressions of trauma and the appropriate treatments cross-culturally. Further, such absolute depictions of trauma not only simplify it as a biological entity to be ‘fixed’, but pathologise human emotions and victims of traumatic events.

“Members and employees past and present of MSF made attempts to challenge their work environment through publishing of an independent report exposing the racism, discrimination, and abhorrent behaviours observed within the organisation.”

The white saviour complex at the centre of MSF's ideology is a symptom of a historical mindset that is accepting of discriminatory language and generalisations. Members and employees past and present of MSF made attempts to challenge their work environment through publishing an independent report exposing the racism, discrimination, and abhorrent behaviours observed within the organisation. As an employee of MSF relays, “I hear harmful generalisations and racist comments all the time when working internationally for MSF, from fellow international colleagues.” Employees went on to take note of their experiences in varied settings, stating they have overheard senior colleagues using hateful and ignorant language such as “These people aren't careful”, “They smell bad”, “People here can't figure it out”, “People here don't know how to do s***.” Yet the organisation's work sustains its faultless appearance, continuing to appeal to the Western eye and be championed for its exemplary humanitarian action.

“MSF joins many other Western non-government organisations in an inability to concede and amend their colonial history, address their white saviorism discourse, and dismantle their archaic protocols and procedures.”

MSF's exacerbation of white supremacy and neo-colonialism—the use of power by developed countries “to produce a colonial-like exploitation” and maintain control—are further evidenced within its division of labour: workers are split into both ‘international’ and ‘national’ categories, providing individuals in the same role with varied rates of pay and privileges dependent on their nationality and passport. Such divisions were described by MSF staff as "coded racialised language", with over 50% of its workers reporting experiences of racism. Since many ‘international’ workers depend on MSF for employment, it is hard for them to confront the administration and demand tough reforms for fear of losing their jobs.

Members of the organisation have made considerable attempts to stand against their work’s ethos, calling for MSF to look deeper into its history and what it represents, and demanding accountability for their harmful actions. Their stance is summarised by present MSF staff in the MSF dignity report published in 2021: it is impossible to view current activities and policies in MSF “outside the legacies of colonialism itself, from which MSF and the wider humanitarian sector grew, or contemporary power dynamics that maintain oppressions”. However, the impact of the report has done little to tarnish the reputation of MSF, or to change the lived experiences of both its staff and those on the receiving end of its ‘aid’. MSF joins many other Western non-government organisations in an inability to concede and amend their colonial history, address their white saviorism discourse, and dismantle their archaic protocols and procedures.

“the West medicalises and objectifies despair—responses to mass social upheaval, poor human rights, and diminishing social security—by categorising them into identifiable somatic symptoms”

The future of trauma narratives

“non-Western expressions of trauma are either falsely medicalised, untreated, misdiagnosed, or underrepresented, leading to inequalities in access to treatment for poor mental health globally”

To conclude, modern Western psychiatry and the clinical protocols and manuals that form it are based on biased Western research and experiences that are not inclusive of other cultural understandings nor the contexts in which mental ill-health arises. It is argued that the West medicalises and objectifies despair—responses to mass social upheaval, poor human rights, and diminishing social security—by categorising them into identifiable somatic symptoms. The 5th and most recent edition of the DSM has been criticised for its cultural bias and tendency to categorise all mental illnesses that do not align with Western understandings of psychology as “culture-bound syndromes”—that is, diseases or illnesses that are deemed to be specific to a particular culture or society. Subsequently, non-Western expressions of trauma are either falsely medicalised, untreated, misdiagnosed, or underrepresented, leading to inequalities in access to treatment for poor mental health globally. Implications of these discriminations bleed into the social lives of those afflicted and can have adverse effects on survivors. As Western diagnoses and understandings are prioritised, traditional coping strategies and idioms of distress are no longer meaningful to discuss patients' suffering, nor utilised as a common language for survivors, therefore exacerbating mental illness itself.

“The decolonisation movement emphasises the diversity of human experience, arguing that no single lens or methodology can encapsulate various understandings, ways of life, or experiences without falling into generalisations and omitting elements of people’s existences.”

To address colonial cycles in healthcare, critics are calling for a decolonised approach to psychology. A decolonised approach places human diversity as a priority in its thinking through actions like rewriting the curriculum used in medical schools to expand upon the limited Western frameworks currently used. The decolonisation movement emphasises the diversity of human experience, arguing that no single lens or methodology can encapsulate various understandings, ways of life, or experiences without falling into generalisations and omitting elements of people’s existences. In the case of NGOs such as MSF, training should be provided to inform their staff of the cultures that they work in. Learning about the ideas and practices intrinsic to other cultures would be a step towards acknowledging the gap between their expertise and those of local healthcare workers, community leaders, and healers. Culturally-cognisant work empowers locals to lead humanitarian agencies towards the concerns of their survivor groups, and guide them in understanding their way of life through respecting their rights, integrity, and traditional ways of coping.

Improving nuance in South Asian immigrant mental healthcare

Pallavi discusses the ways in which Western approaches to mental healthcare fail to recognise the nuances of immigrant communities, cultures, and conceptions of self.

If there is anything the pandemic has shown us, it is that isolation is exceptionally rattling. A June 2020 survey by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 40.19% of adults were experiencing depression, anxiety, PTSD, or substance abuse in the United States. This was three to four times higher than the rates reported just the year prior. Thus, the need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations. Yet, the diagnosis and treatments we assign to these mental health conditions often do not recognise nor appropriately address these differences. While there is some degree of universality in the human experience, there must be greater nuance and understanding in how we provide mental healthcare, especially in vulnerable and underserved populations. To illustrate this need, I will specifically be looking at how mental health is diagnosed and treated in the United States (US) and how this approach often does not work for the South Asian population here.

Image credit: Unsplash

“The need for appropriate mental health interventions is higher than ever. Neither the effects of the pandemic nor healthcare needs are uniform across populations.”

The medical system in the US is ascribed by the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V). The DSM-V is a collaborative work created by mental health professionals to lay out guidelines for appropriately diagnosing someone with a mental health condition. Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common, annually affecting 19.1% and 10.4% of American adults respectively. For a patient suffering from anxiety, the DSM-V lays out symptoms and the level of daily impairment a patient must be experiencing to receive a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). These include the duration, breadth, and content of anxiety, as well as the presence of somatic symptoms, such as fatigue or restlessness, not explained by a different physiological cause. While the treatment varies across conditions, the overarching principle remains the same: the evidence we have supports a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. A patient diagnosed with GAD is likely to be prescribed a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) and is recommended for a therapy programme, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. Although this is considered standard treatment, the success rate of this regimen broadly varies. This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients with GAD may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways. While there are many components missing in this model, I will delve into three that I have found to be largely absent.

“This model of mental healthcare does not consistently consider that two patients may have vastly different cultures, values, and stories, and thus may experience their disorders in very different ways.”

Mental health diagnosis and treatment largely rely on using the individual as the focal point. As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold. In South Asian cultures, there is a high degree of interconnectedness between families and communities, spanning generations. Thus, the concept of ‘the individual’ is diluted. There is a protective element here; ideally, the burdens that one person may have to carry will be bolstered by a community. However, in a dysfunctional dynamic, the diminishment of the individual sphere turns into undue burdens forcibly carried by many. This ties in with the idea of intergenerational trauma. Young South Asian Americans today are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who lived to see the end of colonialism in India. Many are children of parents who immigrated to the West, facing poverty, racism, and uncertainty in a new country. These are not easy events for any generation to cope with, let alone within South Asian culture, where traumatic events are not openly spoken about. There is a profound alteration of sense of self that comes with traumatic occurrences, which can be greatly magnified when it occurs within a culture that also de-emphasises the individual. A communal notion of self can also make it difficult for a person to recognise intergenerational patterns that may be harming them. Contingently, a collectivist focus makes it difficult for many South Asians—whether they are from the era of Indian independence or they are influenced by modern-day societies—to buy into a mental healthcare system that places focus largely on the individual.

Image credit: Unsplash

“As a part of the South Asian community, I have felt caught between the Western sense of self that contrasts sharply with the more collectivist ideals that South Asian cultures hold.”

Language is another major barrier in providing nuanced mental healthcare. As clinicians, we use terms like “major depressive disorder” and “generalised anxiety disorder” to demystify. These labels make sense for those who work in healthcare, but what do they really mean to individuals who have never heard these terms before? What do they mean to those who do not speak English? The majority of the clinical language used to describe mental health come from a Western context and are amenable to English speakers. As seen by the portrayals in South Asian media, including cinema, a large number of South Asian languages do not use or have words that speak extensively or objectively about mental health. Thus, it becomes difficult for people to be aware of these issues, let alone act against the stigma around them, when there are barriers for communicating about them.

Finally, each community should be framed within the context of how they view the healthcare system. Like many immigrant communities, there is a degree of mistrust regarding healthcare amongst South Asians. Given the rich history of Eastern medicine within the region, there is an ongoing balance between how much trust the community will divvy up between these traditional, generational healing practices, and Western medicine. A 2016 study in BMC Endocrine Disorders looked at South Asian opinions on diabetes medicine and found a prevalent theme of scepticism. Many of those surveyed worried about drug toxicity, drug interactions, appropriateness of their therapies, and more. Doubt in the healthcare system, coupled with the underlying stigma and shame that South Asian communities hold towards mental health conditions, makes it all the more difficult to seek out help. As many South Asian languages do not have words to describe mental health conditions, negative terms end up being used in their place, increasing the shame around these conditions. According to a 2019 review, shame is deeply woven into the South Asian community and acts as a major barrier towards acceptance and treatment of mental health disorders. Stigma also creates a paradoxical problem: although South Asian cultures are largely collectivistic, the shame surrounding mental health is often so potent that any such problems become the individual’s fault. The effects of this can be devastating. Interconnectedness creates an erosion of the sense of self that is not particularly conducive to handling major stressors and mental health concerns.

Image credit: Unsplash

“Healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health.”

Ultimately, these are only some of the barriers facing South Asian immigrant mental healthcare. There are countless other cultures and innumerable nuances that need to be understood in caring for their mental health. It would be impossible to expect public and clinic health providers to be well versed in the struggles of every community. The idea of culturally competent care—which refers to the ability of healthcare professionals to understand, respect, and interact with patients with cultures and value systems different from their own—recognises this. The core principle here is curiosity; healthcare workers should be trained to at least seek out context regarding how a culture views the sphere of the individual, and how its people regard mental health. Care must also be framed within the context of how the culture views Western healthcare as well as the stigmas it holds regarding not only Western medicine, but mental health overall. For an arena as complex as mental health, there are no clear-cut answers. Simply put, nuance is needed to fight our myopia when it comes to sensitive care in immigrant communities.

Artist spotlight: Becki

Po Ruby speaks to Becki, a multimedia artist who uses creativity as a way to channel difficult thoughts and emotions into something positive.

Content warning: This article contains discussions of self-harm.

Becki is a multimedia artist and writer from Cardiff, Wales. Her work is influenced by her interests in philosophy, psychology, and esoterica. We connected to talk about art as a coping mechanism, transformative materials, and the power of colour.

Po: Where are you from and where did you grow up?

Becki: I’m from Cardiff, and I’ve lived in South Wales my whole life. My Welsh identity is really important to me. Although none of the adults who raised me speak any Welsh, I’m raising my own son to be bilingual. Culturally, a lot of my family comes from an Irish Catholic background, so I feel deeply Celtic and not at all British.

Everything is going to be alright

Image credit: Becki

What place did creativity have in your life when you were growing up?

Creativity was always an escape for me. From a very young age I was a voracious reader, and I used my vivid imagination to create fantasy worlds to play in. But coming from a low-income working-class home, most of the life advice I was given was to study something academic that would lead to a well-paid career and financial security. So, I pursued academic subjects that allowed me to at least think creatively, and gained my degree in Politics and Philosophy from Cardiff University.

When did you start making art on a more regular basis, and what spurred you to do so?

During my degree, art came crashing back into my life after a series of realisations about my health and the support I received as a result. Living independently for the first time was a real struggle for me—I had trouble managing my time, juggling work, studying, and keeping track of all the things I was supposed to do. Eventually I missed an exam because I genuinely just got the time wrong, and I was diagnosed with dyspraxia through the student support service.

I was also very depressed and anxious at university. I self-harmed regularly from the age of 14, but during my first year at university it became a nearly daily habit, and I was drinking huge amounts of alcohol and smoking cigarettes to self-medicate. People who knew me at that time have since told me, “I honestly thought you were going to end up dead.”

Stay here

Image credit: Becki

It was during this destructive cycle that I met Hannah Morgan, and it was literally life changing. Hannah was the first person I’d ever met who had been in a similar position to myself and had come out the other side. She was in the process of setting up Heads Above The Waves, a non-profit supporting young people with mental health problems. Along with her co-founder, Si, Hannah helped me to realise that I had the power to stop hurting myself and to channel that emotional energy in other ways.

As a result of her advice and support, I returned to creativity. At first my creations were very dark—literally and emotionally—as I processed difficult experiences. I didn’t have much money, so I worked a lot with found and recycled materials: collaging with cut up cereal boxes, sweet wrappers, and junk mail. These creations shifted my perspective, and I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis. I haven’t stopped creating since then.

You are who you have always been

Image credit: Becki

“I began to see art as a tool that I could turn to when I needed a distraction or catharsis.”

You experiment with mixed mediums in your artwork. What do these materials mean to you?

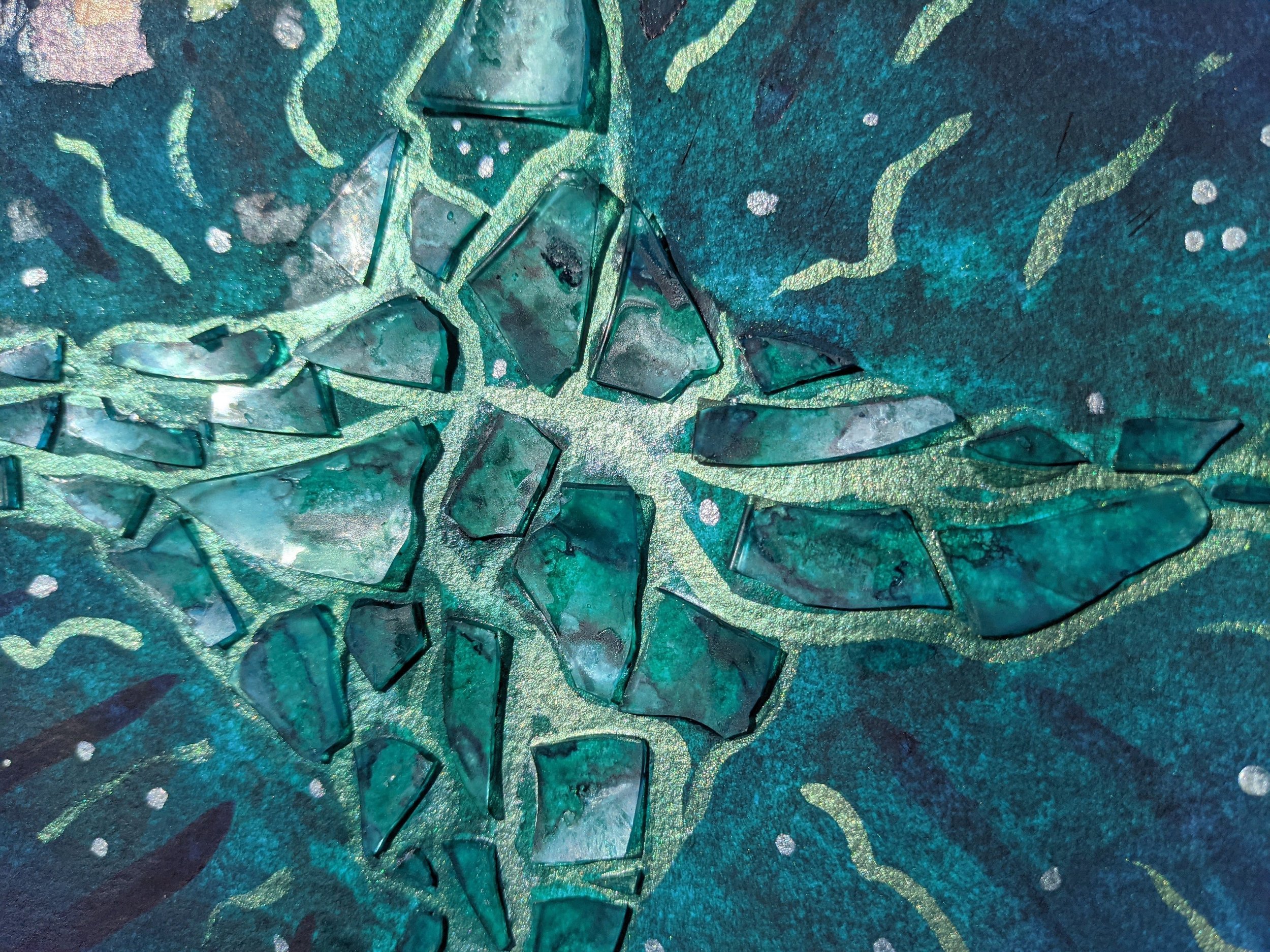

Broken glass, in particular, holds a lot of emotional significance for me. I frequently have accidents and break things, which I now know is due to dyspraxia. But before I was diagnosed, I got into trouble a lot for being “careless”, “thoughtless”, and “ungrateful”. I internalised these criticisms and saw every broken cup as evidence of how deeply terrible I was. It was because of these feelings that I first picked up a shard of a glass I’d just dropped and used it to cut myself.

Glass was my tool of choice for self-harm, and I was never short of it, so using it in my artwork feels transformational, alchemical; I’m taking something with intense negative associations and making it neutral. In my latest collection, I feel like the watercolours represent the soul, or personality, and the glass is trauma. Trauma happens to all of us: it’s undeniable and it shapes the way we develop. But our soul and personality hold the potential of absorbing and growing around these painful experiences to become a more complex and beautiful version of who we already were. I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them. But I do think it’s valuable and an important part of the healing process to look directly at the trauma and acknowledge the tangible ways it has affected you.

“I don’t like the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”; I don’t think survivors should have to feel grateful for the awful things that have happened to them.”

The cracks are how the light gets in

Image credit: Becki

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic process: is creativity spontaneous for you, or do you choose a time and place to work on an art piece?

Both! I’ve worked hard to learn to use art as a replacement for self-destructive behaviours or as a reaction to overwhelming experiences. I have stashed notebooks and scrapbooks in every room of the house, and whenever I feel the need, I grab one and doodle or write whatever it is that I need to get out of my head. Sometimes I just grab a stack of magazines and start flicking through and ripping things out with no plan in mind, just to occupy my hands while my mind-body relaxes.

I also plan pieces that I want to make, sketch them in a scrapbook, and then create them carefully over the course of several days. I find that having regular practice gives me the space to keep my mind calm day-to-day. Painting, collaging, building glass mosaics with tweezers: these are my versions of meditation. I can’t sit still and think of nothing, that’s impossibly uncomfortable for me, but I can be present with myself on the page.

Do you create art primarily for yourself?

At first it was mostly for myself, but since I started working with Heads Above The Waves, I began to focus more on the positive side. I didn’t want my art to be a rumination on all the depths of my lowest moments; I want it to be a little beacon of hope and for people to see it and feel that they’re not alone.

On your Instagram page your bio reads “turning wounds into wisdom”. What does this mean with regard to your art?

Still expanding

Image credit: Becki

I actually have a tattoo that reads “turn your wounds into wisdom”. I’ve held onto this idea for a long time: I’m not broken, or damaged—I’m learning. This is the value I can bring to my community: my experience, my healing, the lessons I’ve learned. I want to help people find the path out of their pain.

Unlike a lot of art that centres around themes of pain, madness, and politics, your work is comparatively very pretty and colourful. Is this a conscious choice?

Absolutely. I feel like colour has so much power, and I think there’s already more than enough art that dwells on the darker side of things. For me, I find comfort in numinous colour, and in remembering the scope and depth of beauty that exists. In an ideal world, looking at my art would remind others of this scope and beauty, too.

You identify yourself as Welsh, neurodivergent, chronically ill, and queer. How do these identities overlap and impact your creative process?

These labels are important to me because they are the communities that have welcomed me, held me, and allowed me to discover myself. Along with my diagnosis of dyspraxia, I have Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), and developed fibromyalgia following a pulmonary embolism in 2016. I think there’s a common feeling of relief among many neurodivergent and chronically ill people in finding online communities and suddenly connecting with other people living a similar experience as you. Finding these communities has made my life bearable in ways that I can’t completely articulate, but my creativity is often a reflection of these identities and processes.

You deserve good love

Image credit: Becki

We spoke about the potential of you doing an exhibition with Heads Above the Waves in the future. What draws you to this possibility?

Without Heads Above The Waves, I don’t think I would be an artist today. I might not even be alive. Putting work out into the world where it can reach people could make a tangible change for somebody who needs one. It feels valuable to be both carving this path for myself, and sharing as I go for the benefit of others coming after. I want to prove (to myself as much as anyone else) that it’s possible to live a balanced, fulfilling life as a disabled, chronically ill person.

Heads Above The Waves is a non-for-profit organisation that raises awareness of depression and self-harm in young people. They promote positive and creative ways of dealing with bad days. Advice, positive coping techniques, and other people’s experiences can be found on their website.

For urgent support in the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or you can email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org

Potential health benefits of companion animals

Akshay shares his love of companion animals with us and enumerates the (evidence-backed) benefits of having pets.

The feeling of coming home to an excited furry friend wagging its tail is unparalleled. Ask anyone with pets how their lives have been enriched and every single one will come up with a long and compelling list of benefits. It is perhaps due to the pandemic lockdowns and ensuing isolation that millions of people across the world have adopted pets over the last year. In the United Kingdom alone, nearly 3.2 million households welcomed pets into their homes. Given this current trend, it seems like a relevant time to explore the science behind the health benefits of companion animals.

Image credit: @thedoggozoey on Instagram

Mental health benefits

Pets can be cuddly, loving, and a great source of companionship. Dr. Gregory Fricchione observes, "We do best medically and emotionally when we feel securely attached to another, because we're mammals and that's the way we've evolved.” According to Fricchione, we are particularly comfortable with cats and dogs because they convey a feeling of unconditional love.

“Having a pet during childhood and adolescence has a wide array of mental health benefits.”

A number of scientific studies provide evidence for the benefits of such human-animal companionship. Having a pet during childhood and adolescence has a wide array of mental health benefits ranging from improved self-esteem, reduced feelings of loneliness, increased social competence, and even an improvement in intellectual and cognitive abilities. Among the elderly, companion animals can improve quality of life and reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and behavioural and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Having a pet, however, can also have negative effects on our mental health. While people living with mental health problems do experience the benefits outlined above, they are also exposed to additional risks, such as the psychological distress of losing a pet.

Physical health benefits

Pets can also help with our physical health. Having a pet can encourage people to go outside and exercise; people with dogs, for example, walk more and engage in more physical activity than those without. In the case of certain diseases, there is some evidence to show that having a pet is associated with reduced severity and lower mortality: studies indicate, for example, that people with pets have a lower prevalence of systemic hypertension and lower adjusted cardiovascular mortality.

When should you perhaps think twice about getting a pet?

While there are health benefits to having a pet, there are specific situations in which having one may not be advised. For people with mental health conditions, the distress of losing a pet can be significant; in times of crisis, this grief can exacerbate a mental health condition that they may already be struggling to manage. As for risks to physical health, people with weakened immune systems, and those undergoing cancer chemotherapy, ought to take precautions to avoid contracting zoonotic diseases—those transmissible between animals and humans. For pregnant women, the Centres for Disease Control advises against handling new or stray cats so as to avoid the risk of contracting toxoplasmosis, a parasite-borne illness that can lead to birth defects.

For those not subject to such concerns, however, the benefits of a companion animal are compelling. If you are contemplating getting a cuddly, furry-tailed friend, and cannot resist those puppy dog eyes at the shelter, then do not worry, for science is on your side.

Artist spotlight: David

Gwen features the works and journey of artist, photographer, and entrepreneur, David. David advocates for physical and mental wellbeing to support the health of communities.

Content warning: this article contains mentions of racism and mental illness.

Back in 2019, David Lee turned his camera towards me. I felt self-conscious and suddenly didn’t know how to be natural in my own skin. But his approach to photography centred on connection and introspection, which made the experience more like a cathartic release than a purely aesthetic pursuit. He gave me the opportunity to talk about the things that were on my mind and reminded me how to be myself again. David and I met as community advocates who were still exploring the ways that we fit into supporting the social, environmental, economic, and health needs of our microcosm of community. Most of our conversations were about how we work in relationship to the community and how we take care of ourselves. That night in my flat we had the same conversation but somehow it felt more vulnerable to have a camera there and to have it be documented: at the same time, it was therapeutic to have those moments preserved. David has taken that intimacy of documentation and turned it into his full-time pursuit as a photographer and artist.

Photography by David Lee

Creativity has always had a place in David’s life, but his emergence as a creative was tangled with his identity and wrangling with others’ perceptions of him. He recalls that different learning environments impacted the reception of his art by his teachers. Early on he was not encouraged to pursue art, which raised larger questions on how stereotyped identities, specifically expectations of black people, can hinder and limit growth. “I think sometimes black people are expected to perform in certain ways … looking back I didn’t get the encouragement like my peers did, and I won’t say why, but I noticed that, and it got to me.”

Photography by David Lee

Initially, this kept David from identifying as a creative. It wasn’t until middle school that his poetry was recognised and won a competition. “I remember winning that and the first time feeling like I was a creative. Like my school actually did think it was a big deal. The school was majority black and that was the first time I went to a predominantly black school.” This recognition and ability to self-identify as someone who is creative gave David license to continue exploring his art, which soon led him to photography.

His exploration of photography began as an ode to memories and an outlet for his own depression. Looking through old family photos in what his family called their “library”, David became interested in photos and memory. “These memories are important. I realised how important they were to me. So, I went and bought a bunch of disposable cameras and went around taking pictures of middle school.” Reflecting back on this period of time, David recounts some of his own struggles with depression and finding photography and poetry as a means of dealing with his own internal world.

“I can see that’s when my childhood depression started to manifest the most and so I needed these outlets. Friendships were starting to look weird … my art usually centres around mental health and trying to create these outlets of expression so people can process and see themselves reflected back. I think that’s when it started for me.”

Photography by David Lee

Memories of middle school years are ones he has shared with me a couple times, and it brings together so many aspects of David that I’ve come to know. He has an incredible ability to capture vulnerable, authentic moments. Part of his art is tapping into the undercurrent of a moment and pulling out the right words and images that describe some of those unspoken emotions. Photography is his way of slowing things down in an age of hyper-stimulation. “It’s a chance to press pause and allow people to go back to that moment and think about what they were feeling and see the subtleties of who they are”. Oftentimes, David shares his photos with poems and prose about that moment, the interaction, or what the experience brought him. Whenever I see David’s work, photography and poetry paired together, there is no doubt it’s his voice and vision that come through.

Photography by David Lee

“Photography is his way of slowing things down in an age of hyper-stimulation. “It’s a chance to press pause and allow people to go back to that moment and think about what they were feeling and see the subtleties of who they are.””

During the summer of 2020, George Floyd was murdered. Black Lives Matter protests spread across the United States and around the world. David was there—documenting through his lens the rawness of the people, the protests, the events, and the emotions.

The pandemic was ongoing in the backdrop, which brought into sharp focus health inequities, particularly in black communities. The broader social conversation around racism, critiques of the carceral system, and health inequities shifted—it was suddenly more critical, urgent, and mainstream. “During those protests I realised this wasn’t my space anymore. I started to see allies showing up and screaming at the top of their lungs, with signs and linking arms on the frontlines. Like ‘Huh, cool it’s been done’ and it felt like the energy shifted. So where do I need to go if this isn’t the space, because the work needs to continue. I chose physical health, community, and mental health. Getting outdoors was the way to do it.” The protests in 2020 felt different to him and having allies show up in those spaces offered David the flexibility to do the work he really wanted to do. This was when he transitioned to being a full-time co-founder and photographer.

Photography by David Lee

Choosing the name of his organisation was an act of radical self-naming and claiming an identity. David reflects: “How is that going to come off to people, is that marketable? But in my community it’s important to say this is who we are and not allow other people to dictate what our expression should be. … So, I started the organisation Negus in Nature (NIN) with my business partner Langston”.

Within NIN, David is in his element—sharing the joys of the back country while documenting a community becoming connected with their mental and physical wellbeing outdoors. He’ll be starting his artist residency at the Kala Institute, which will give him access to an array of mixed media materials. He’s really excited to be sharing some of his new works coming up as he says, “A lot of the protest photos I have not shared yet because it’s like ‘aight this is raw and I don’t know what this is for just yet … and so now everything is coming together and it’s this collective idea of ‘this is where I was in the pandemic and this is where I was before and this is the processing.’” He wouldn’t share much more about his upcoming project, but he’s dreaming up something with paper mâché, dabbling into the world of mixed media.

Stay up to date with David’s projects on Instagram: @d.xoti

You can follow NIN’s adventures on Instagram: @negusinnature

If you want to sign up for an excursion you can visit NIN’s website