The female contraceptive pill: empowering or oppressive?

A personal view of the pill’s usefulness

Content Warning: This article discusses issues around non consensual sex, trauma, and medical abuse.

The intrauterine device (IUD), alternatively known as the contraceptive coil, has been in the news recently. High-profile women* have been recounting painful experiences of getting the device fitted and removed, with many expressing a feeling that pain and discomfort was a price to pay and endure for reproductive rights. But the coil is not unique in its issues: there is a long history of controversy, and even exploitation, surrounding contraception in general, which continues into the 21st century. Contraception is commonly understood as a vital part of socio-economic development, giving women agency over their own bodies, more education, and increased economic independence. But is the story as simple as that? I’m a white woman living in a high-income country (HIC), and even with the knowledge and rights that affords me, I’m still not sure whether I have made the right contraceptive choices, particularly when it comes to taking the contraceptive pill.

Image Credit: Unsplash

But before delving into the potential rights and wrongs of the pill, let’s take a quick look back at the history of contraception. It’s not a new phenomenon—forms of contraception have been documented as early as 1850 BC in Egypt in the Kahun papyrus, utilising ingredients such as acacia gum, which has since been found to have spermicidal properties. Types of protective sheath or condom have also been available for thousands of years, using materials ranging from thin leather to animal intestines, oiled paper and even tortoiseshell. It was in 1882 that the diaphragm was invented—the first safe and reliable method of separating sex and reproduction, and one which women themselves could have control over—which initiated the start of modern female contraception. By the 1960s, the pill was approved for use, allowing the postponement of having children or spacing births, and enabling women to join the workforce en masse.

The pill was not perfect, though. When it arrived in the UK in 1961, it was only available on the National Health Service (NHS) to married women. Moreover, without longitudinal studies, women taking the pill were effectively part of a huge experiment on the long-term effects of hormone ingestion. Most shockingly, women were not told about these unknowns.

Feminists in the ‘60s believed the pill was co-opted by men to serve their own agenda. Barbara Seaman quoted Doctor Frederick Robbins in her controversial 1969 book The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill: “the dangers of overpopulation are so great that we may have to use certain techniques of contraception that may entail considerable risk to the individual woman.” This book prompted US Senate hearings in 1970 (of course, no women were invited to testify) that led to a warning label on oral contraceptives and the drastic lowering of oestrogen doses due to dangerous health effects.

This same hearing prompted widespread use of a newer form of IUD—the Dalkon shield—after its inventor testified that IUDs were safer and more effective. But after its release in 1970 this device caused septic infection, infertility, miscarriage, and an array of other related complications, including death. At its peak in the US, it was used by millions of women. It took 15 years for its manufacturers to issue a statement advising the removal of the shield, but only after hundreds of thousands of women had suffered infection or worse. The shield was also sold to low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) after it was withdrawn from US markets. This blatant misconduct and exploitation of women to fill white collar men’s pockets is an important part of contraceptive history, as is the exploitation in particular of black women and the global majority.

While the modern IUD in its various forms is vastly safer, more successful, and for many women a perfect solution, it can have issues: women have reported being in agony when it was fitted and describe their experience as traumatising. Experiences like these cannot be ignored or called ‘normal’. Extreme pain and trauma shouldn’t be the price to pay for reproductive rights, nor should it be downplayed.

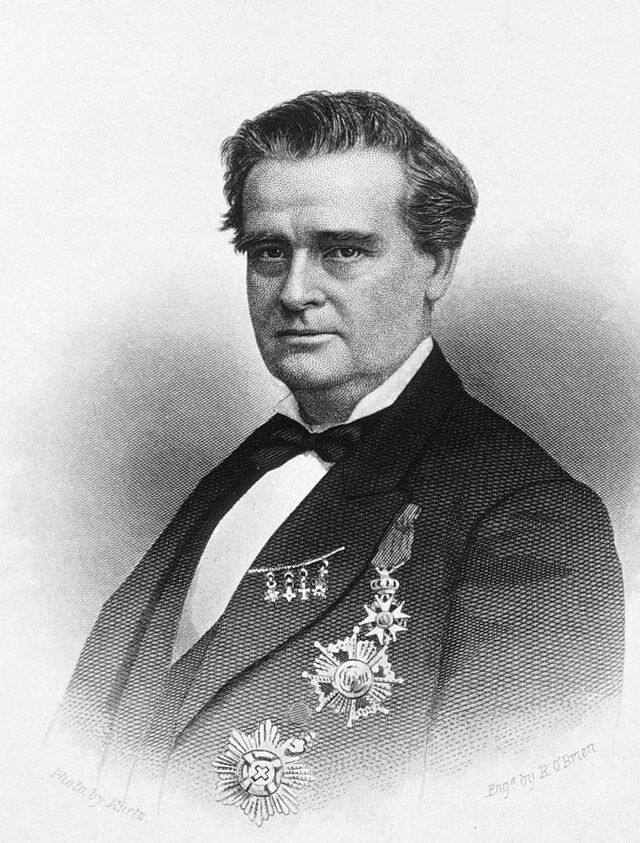

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

James Marion Sims

It is relatively well known that J. Marion Sims, the so-called ‘father of Gynaecology’ operated on countless, nameless black and poor women, often without anaesthesia, to build the foundations of modern (Western) gynaecology. The pill has its own complicated history, with Puerto Rican women being experimented on during clinical trials. It is a theme of modern contraception that it has been used to overtly oppress minority groups—these women cannot be ignored in conversations surrounding the pill. It is vital that we include women of colour, disabled women, incarcerated women, and impoverished women when discussing reproductive freedoms and modern contraceptive methods. Events like these have helped sow the seeds of mistrust among many. At the same time however, modern contraception has advanced to be a vital component of Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, and Child Health (RMNCH) care, especially for women living in lower-resource settings where it can be one of the few forms of agency women have access to. Do the ends justify the means? I can only hope that we’ve learned from our mistakes and won’t allow women to be exploited for the sake of medical advancement anymore.

But if we think we have control now over our reproductive rights, think again. The wide availability of oral contraception brought with it new problems for women. Where before we could retreat from unwanted sex by pleading fear of pregnancy, we now have to learn to be honest and say “no” without feeling guilty or embarrassed. This isn’t always easy to do. Feminists in the 1970s spoke about how women would rather give in than be thought of as puritanical and old-fashioned: many men had found a way to turn new-found freedom into a new form of oppression. Being on the pill has become synonymous with wanting to have sex regardless of consent or desire. I’ve lost count of the number of times men have substituted the phrase “do you want to have sex?” for “are you on the pill?”, and if the answer is “yes”, it is often taken as consent. Saying “no” is hard and sometimes scary. If a woman says no, there’s a chance her partner may not listen, turning the scenario into something even more terrifying. Sometimes it’s easier to let sex happen than deal with the alternative.

But is this a problem with the pill itself, or a symptom of how consent is obtained? I think the latter. Teaching children how to obtain and recognise consent is vital. But, when I grew up, it wasn’t something that was given much emphasis in my school. It shouldn’t stop with school either: universities and places of work should have mandatory consent training, because women feeling like they need any excuse other than to simply say “I don’t want to have sex” is unacceptable.

Moreover, if women do find themselves in a situation where they aren’t fully in control, then knowing they are at least protected from pregnancy is important, and the pill can do this—studies have shown that intimate partner violence reduces condom use. And let’s also remember that beyond the sexual freedom it gives, the pill can also help with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, acne, and sometimes just controlling the length of cycles. Many people have positive experiences with the pill and other methods of female contraception, and there’s no doubt that using the pill can be life-changing.

So, it’s true that people have good experiences with the pill, but has it changed the way we look at our cycles? People who menstruate are taught by society from a young age that periods are dirty things to be covered up at all costs—whether it be slipping a tampon up their sleeve or going on the pill to stop or control their periods. They are a nuisance. An inconvenience. The start of menstruation is overshadowed—in LMICs and HICs—by inadequate access to hygiene products, knowledge gaps, silence, myths, misconceptions, and social restrictions. This is where my experiences of the pill come in: As stated, I’m a well-educated white woman. My mother is a well-informed feminist. Yet I went on the pill at 14 to regulate my cycle with no clue how important periods are, the side effects, or why I felt shame towards my period. I lost my period for 2 years after coming off the pill thanks to an eating disorder, but I didn’t know anything was wrong before that because the hormones I was taking gave me a ‘fake period’. I now know that having a cycle is so important: period loss can result in impaired cognitive function, loss of bone mineral density (leading to osteoporosis), fatigue, insomnia, low libido, and more. I still blame myself for not realising there was something wrong, and I blame the pill for concealing the side effect of what would have been period loss—would it have changed anything if I’d noticed?

The medical technology to create a hormonal male contraceptive has existed for decades but never came to market because of ‘too many side effects’. These side effects included mood swings, libido changes, and depression. For context, side effects of the female contraceptive pill include mood swings, libido changes, and depression. More recently, hormone-free methods have emerged—methods blocking or inhibiting the movement of semen. In more optimistic moments, I hope these will gain some traction. But in the meantime the burden of the responsibility of contraception is disproportionately placed on women—a task that often requires mental and emotional labour, and these normative expectations can even be perpetuated by healthcare providers.

Feminism is about women having the autonomy to make their own choices and do what they want with their body. If this includes taking the pill to protect against pregnancy or regulate our cycle, then that’s our prerogative. When I began writing this piece, I thought I would conclude that the pill isn’t all that great—blinded by my own experience—but now I’m not so sure. I don’t think any of the issues I’ve presented above are the fault of the pill itself, but rather the fault of ineffective education, corrupt people in power, and the societal web poisoned by misogyny in which we exist. We shouldn’t have to ask whether the ends justify the means because the means shouldn’t exploit people in the first place. Medical professionals need to understand all these nuances better. We need to be taught about consent. We need to be taught the complete story of contraception in school—not to scare people who menstruate, but to empower them to make their own informed decisions, because that’s an issue here. Young people who go on the pill, and even older individuals, might be consenting to it, but it is rarely informed consent. We need to rethink the way we teach children about sex, contraception, gender, sexuality, and general health, and ensure we include all genders as part of these conversations.

*Please note that when I’m referring to women, I include all people with wombs, those socialised as women, and those who identify as women and have to navigate sex as a woman.