Power of the written word

Poetry for sexual and reproductive health justice

Content Warning: this article discusses gender-based and sexual violence.

In late 2021, Sexual Reproductive Health Matters (SRHM) proved that it was “more than a journal” with a call out for poetry on sexual and reproductive justice from anyone, anywhere in the world. Given the limited use of creative expression in academic publishing, this call and its subsequent success is an interesting disruption to the scientific paper format, which is now over 400 years old.

Image credit: Unsplash

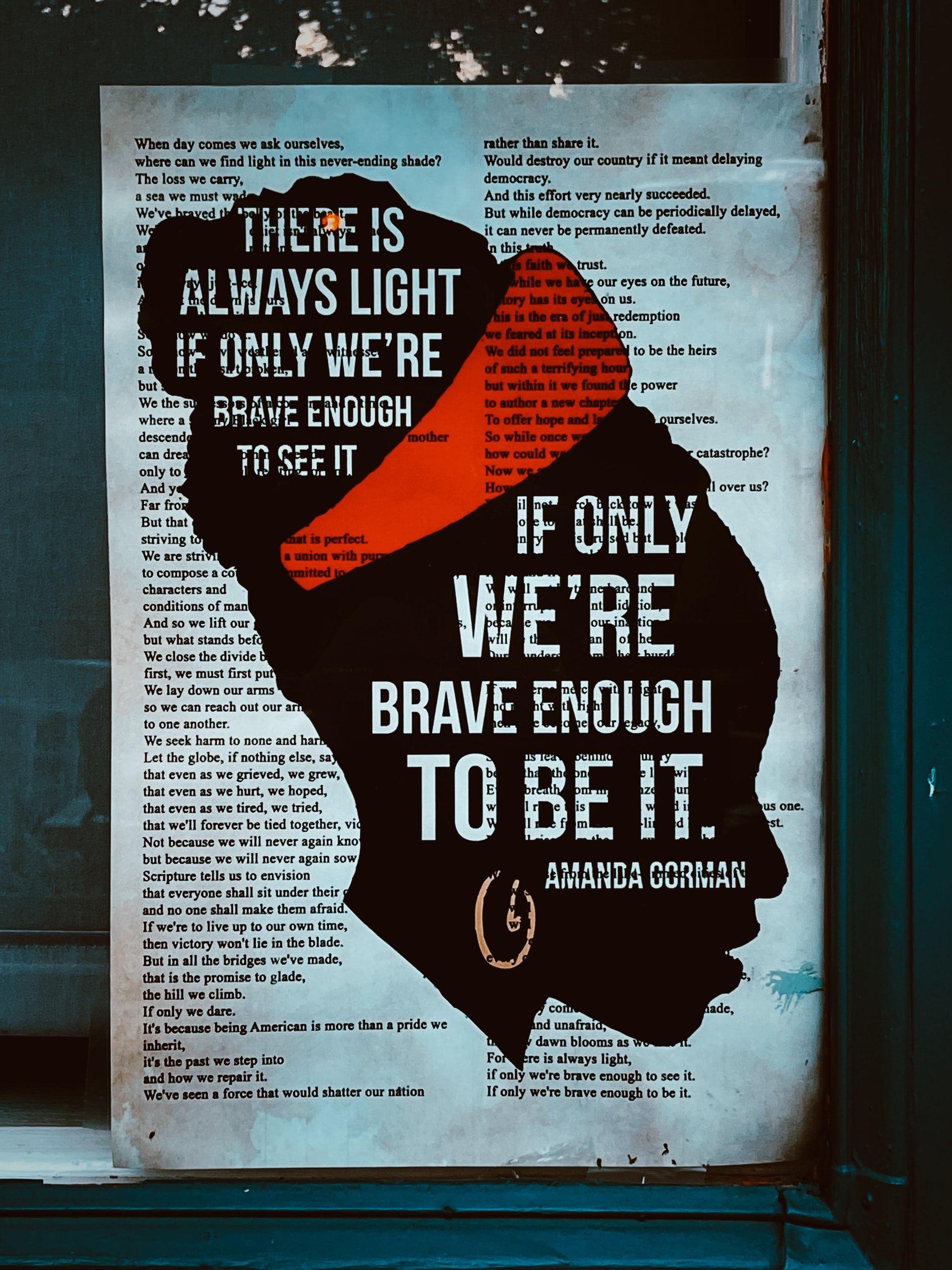

Poetry and spoken word can be accessible formats for people to share and engage with issues that can otherwise be challenging to talk about. It has shown to be a useful tool for activism and empowerment, and played a crucial role in movements including women’s rights advocacy and Black Lives Matter. This is also true when it comes to SRH justice issues more specifically, where poetry has been deployed as a tool for numerous individuals to speak up and express what they have faced or witnessed in the world. For example, Rupi Kaur’s 2015 photography on menstruation was shared widely on social media and later prompted her poetry collections on sexual violence. The inaugural poet for Joe Biden, Amanda Gorman, also used her platform to discuss and raise awareness about abortion rights.

Sexual and reproductive justice is actively being challenged on both international and national stages today. An increase in populist movements and the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic have worsened the situation. The deeply political nature of sexual and reproductive justice is why activism is so important.

At the time of my writing this, there have already been 30 poems published on the SRHM website, with more expected over the coming weeks. The culmination of which will be a full anthology set to launch on Women’s Day in March of this year. I have been following the publication of poems in SRHM—both on social media and on their website—and became curious to know who was behind each of these.

To get a better insight into the personal drivers of writing on sexual and reproductive justice issues, I spoke in-depth and separately with three poets whose work has been published in the SRHM: Elizabeth Wright Veintimilla, Hope Netshivhambe, and Laura Warner.

Writing to fill the silence

I invited each poet to speak about why they chose to write about their respective topics, which cover issues related to infertility, violence, and human rights. They described poetry as a form of activism; a way to engage with themselves and others on important topics.

For Hope, poetry can be used as a tool to “speak to something”, to cover topics that are deeply personal. “There is power in storytelling; I believe in its power and influence.” Hope writes primarily about love, queer experiences, and gender-based violence.

“There is power in storytelling”

For Laura, poetry, more so than other mediums, captures the nuances and complications of life, and what it means to live with, for example, a reproductive health condition.

While writing for personal reasons, these writers use the poetic form to also speak to a wider community and reach individuals who have been impacted by the topics they explore in their work.

Elizabeth says her poems “invite people to reflect on what has happened to them”. Stating that most importantly the poetic works need to “start with ourselves” to bring about any change.

Hope shared similar sentiments, describing how making ourselves aware of, and engaging ourselves on issues such as violence, brings us one step closer to connecting with communities and people who have themselves experienced it.

Through their poems, these poets were able to first explore their own views before sharing them with the world.

Elizabeth seeks to heal those around her, as can be seen in her intimate piece ‘For the Women Who Came Before Us’ where she speaks about the varying experiences across different generations—namely between herself and her mother. The powerful repetition of her mother’s words throughout her poem, “I wish I had the strength / to say something when I was your age” captures the progress in sexual and reproductive justice that Elizabeth’s generation has experienced compared with her mother’s generation. It invites the reader to be grateful, prompting them to think about the improvements we’ve seen and the “wins” we’ve had.

Image credit: Elizabeth Wright Veintimilla, showing her and her mother at a women’s rights march. The placard reads “The Fight is Always Intergenerational”.

The silence and stigma that permeates issues related to SRH justice were a common theme across my conversations with the three poets.

For Elizabeth, the act of writing her poem revealed how a platform like this provides “an opportunity to share things that are usually silenced”, such as sex, violence, and reproductive health issues.

This theme is also central to Hope’s poem titled ‘Silence’, which tackles the difficulties women experience when reporting gender-based violence, due to fear of not being taken seriously or believed.

In her piece, ‘Call it by its Name’, Laura captures the hushing that results from using incorrect terminologies around reproductive diagnoses, such as endometriosis, and how this silence needs to be broken. Later in our conversation, she described how she is working to address this by writing frankly and honestly, even when sharing the deeply personal.

On a path towards healing

Despite conducting these interviews through the tired screens of our computers and in the living rooms of our respective homes—South Africa, Ecuador, and the UK—the impact that sharing these poems had on these poets was palpable. The benefit that comes from being able to write something in “your own words” and on topics that are personal and difficult to talk about was a key thread in our discussions.

Like the saying “a problem shared is a problem halved”, Elizabeth spoke on the impact that writing has had on her mental health: “Expressing myself [through poetry] has been a way to manage my mental and emotional health, otherwise it stays within you and in your body.”

Similarly, Hope described the importance of writing and sharing her poetry, stating: “I have shared this [poem], so it does not weigh on me as much.” While she feels poems cannot solve problems on their own, they do have the power to put you on a path towards healing.

For those dealing with a health condition where symptoms can vary, such as endometriosis, Laura described how having a poem to return to was a helpful reminder of the reasons she felt the way she did, whether it was a good day or a and bad day: “Health can be like a collection of poems and they can sit alongside each other and have the same voice, but there are variations in how that voice speaks on different days.”

“[While] poems cannot solve problems on their own, they do have the power to put you on a path towards healing”

The poets’ experiences were often shaped by how they felt they were viewed by others. Having poems published on a public forum, such as the SRHM, is likely to prompt feedback and responses from friends, family, and even strangers. The stigmas attached to SRH can make activists’ work particularly challenging. Reading about these topics can also be painful, and in turn difficult, for readers to engage with.

Elizabeth relayed how the positive responses she has received in regard to her poem “have impacted my perspective of myself, my writing, and my profession” and that they have motivated her to write more as a form of self-expression. This is surely a good outcome for both Elizabeth as she continues the fight, and for her readers to find solace in her work.

For Laura, writing about her symptoms while awaiting an endometriosis diagnosis—“my body remembers the school fire bell it rings my ribcage from evenings through nights hidden parts of me need to bleed but the blood can find no way out scream-pitch the volume makes me retch”—has proved educational for her readers. The responses from those who have shared these experiences have been both validating and positive for her.

Poetry allowed these three poets to not only reach inside themselves to draw on personal experiences relating to topics on SRH justice, but also allowed them to reach outside themselves and touch others, including their family, loved ones, and the public at large. Public health rarely captures the individual experience, yet these poems show that there is potential for the individual within this space to use creative means, both for self-healing and shifting public health narratives more broadly.